Historical notes on plagues in Europe

Michael Magno's Notepad

The bubonic plague of 541 AD is the first major pandemic documented by the chronicles of the time (see Carlo Venuti, Life at the time of the plague, in Quaderni Guarnierani, n.6, 2015). It affected both the Roman-Byzantine Empire and Persia and other eastern regions. Constantinople lost almost half of its inhabitants (then it numbered about two hundred thousand). Thus the doors were opened to the invasions of nomadic peoples from the Arabian peninsula, recently converted to Islam. The plagues devastated continental Europe at least until 760. Christian and Muslim doctors studied the infection, its causes and ways to prevent it, taking up sacred books and classical authors: Thucydides, Galen, Hippocrates, Aristotle, Plato, Rufus of Ephesus and the chroniclers of the Justinian age. Al-Razi (850-923) physician from Baghdad, gave the first clear clinical description of these affections; already in 910 he had treated the symptoms of smallpox. Arabic translations and commentaries on ancient medical texts flourished: it was also thanks to this scientific-literary commitment that the West rediscovered the science of the classical world.

After the so-called rebirth of the year 1000 (demographic expansion, increase in agricultural productivity thanks also to the methods introduced by the Cistercian and Cluniac monks), at the beginning of the 13th century northern Europe (about thirty million inhabitants) underwent a significant change climate, a small “ice age” with harsh winters and humid summers. From the spring of 1315 to 1322 the excessively rainy seasons compromised the production of cereals, grapes and fruit with the destruction of many crops.

Victims of the resulting famine were not only families, but also working animals (oxen, horses) and meat animals (oxen, farm animals). In summers that were too rainy, the humid heat caused parasites and molds to proliferate. New diseases saw the light that killed sheep and cattle. Flocks and herds were killed by the "rinderpest". The population adapted to the consumption of pork, compromising the conservation and reproduction of the livestock. Other measures, such as more frequent sowing and cultivation extended to all available land, did not prove decisive; on the contrary, by depleting the fertility of the land, they produced ever smaller crops.

It is on this Europe, indigent and undernourished, that the catastrophe of the "Black Death" strikes. In the autumn of 1347, twelve Genoese galleys from Constantinople landed in Messina. Among the goods stored in the holds were mice carrying the plague bacillus. From Sicily it spread quickly throughout the Old Continent, exterminating a third of the population. It is the great plague of 1348-1351, which Giovanni Boccaccio placed in the background of the Decameron. The disease, which appeared in Central Asia around the 1920s, reached Crimea by land in 1345; its advance became more rapid when from the commercial ports on the Black Sea it invaded the Mediterranean basin by sea (Constantinople, Alexandria, Cyprus, then Messina, Genoa, Florence, Venice), subsequently flaring up among the peoples of the Islamic Levant and North Africa.

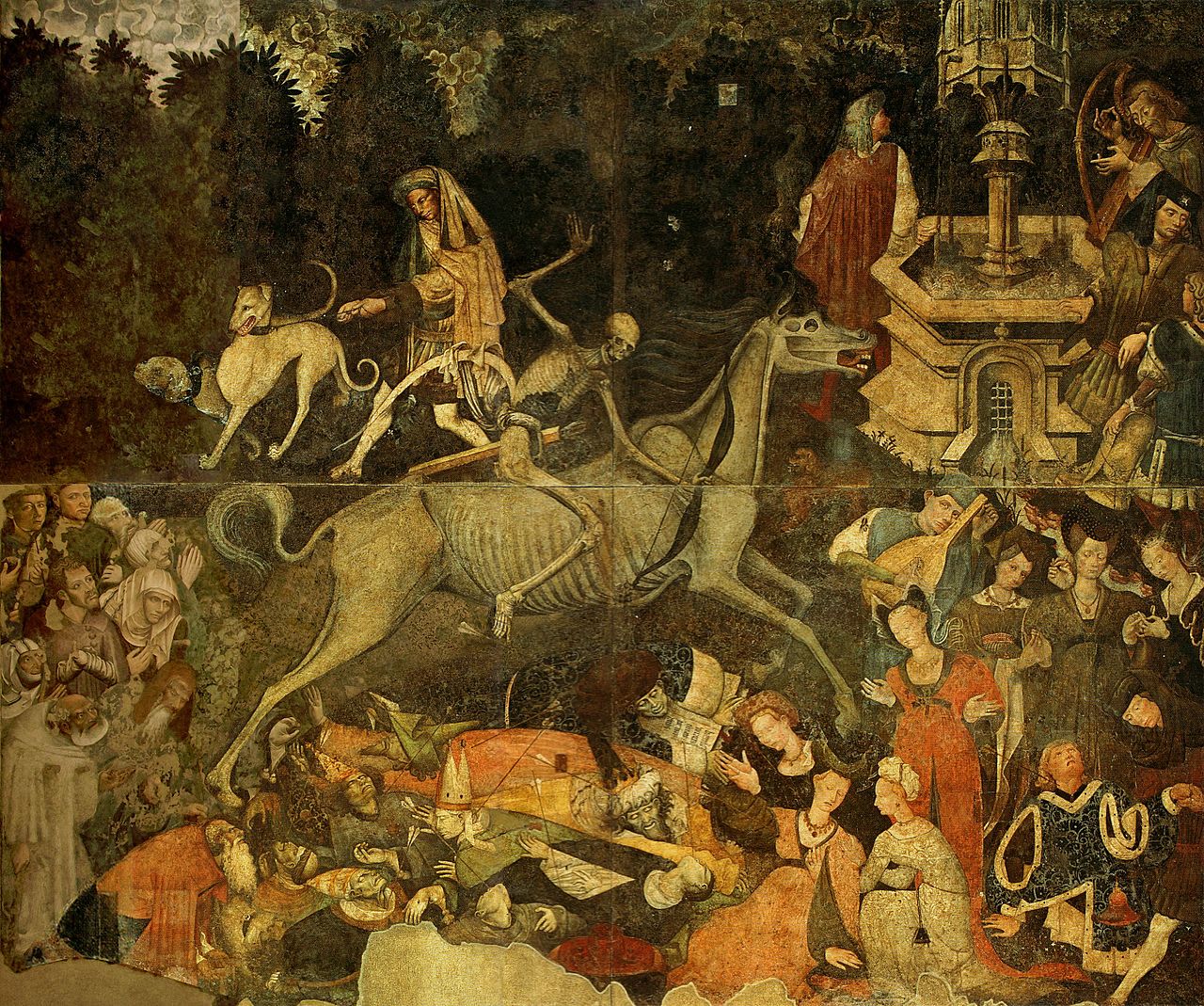

The spread of the plague was favored by the start of the conflict between France and England, which has gone down in history as the "Hundred Years War". Popular iconography represented the disease as a cloud of arrows shot from above, against which St. Sebastian, the third century Roman soldier executed for his faith, acted as a shield. In the Middle Ages it will appear together with Rocco, the saint depicted with a swelling on the thigh, a bubo, in fact. Even the Church, "owner" of the liturgy and cults against the pandemic, suffered heavily from the consequences. Community life of priests, monks, clerics, but also assistance to the infected made the clergy particularly vulnerable. The hygienic and behavioral precautions to which he had to observe loosened pastoral activities, study, formation and religious preparation. The "dancing pilgrims" reappeared, invoking divine protection by scourging themselves in the processions. The fourteenth century ended with the worst infection of the century after the black plague, perhaps introduced in Italy by the French flagellants. However, the epidemics of the fourteenth century brought about a turning point in the history of Western Europe, causing structural changes on the demographic and economic level. In England between the mid-fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, about 1300 urban realities were abandoned.

During the pestiferous pandemic of 1894-1899, the French Swiss doctor Alexander Emile Jean Yersin (1863-1943), at the same time as Shibasaburõ Kitasato (1853-1931), isolated the bacillus of the plague in Hong Kong, which was called "Pasteurella pestis" ( today “Yersinia pestis”): it thrived in the host fleas of rats infected by wild rodents. Probably the original species of "pestiferous rats" lived in India and arrived in Europe through maritime traffic. The city authorities tried to face the emergency with ordinances that limited the freedom of movement and with strict sanitation regulations. We began by isolating the infected areas by hunting out those believed to be carriers of the disease, primarily Jews and foreigners, but also prostitutes and vagabonds. In addition, any source of bad smell was eliminated with the systematic (and positive) collection of leftovers and waste, but reducing the income and employment of leather workers, tanners, butchers, fishmongers, gravediggers.

During epidemics, doctors mostly prescribed more sober diets and lifestyles, the elimination of wet and swampy places, the abolition of sexual licentiousness and begging. But those who best cared for the sick were the doctors: they cut the buboes, practiced bloodletting with leeches, soothing the wounds with the medicines available at the time. However, the etiology of the disease being unknown, effective measures were never taken against rats and other flea-infested animals. The main preventive measures remained the surveillance at the entrance of the cities, the quarantine for the infected, the hospitalization and the construction of the lazarets. In 1488 Milan was equipped with a lazaretto built like a cloister, with a central courtyard surrounded by buildings; followed by Genoa and Florence, then Naples and Rome and other cities. Only in 1600 even the smaller centers had councils, officials and operators employed full time in the health sector.

The plague involved enormous expenses for environmental and clinical investigations, for health professionals and magistrates, for the same care spaces, which public budgets were not always able to support. Hence the imposition of new taxes and duties which aroused growing discontent among the populations. On the other hand, the medicine of the time strictly depended on plant-based drugs: rue, rosemary, onion, vinegar, absinthe and opiates. Chemical physicians, despised by those of philosophical training, also recommended amulets of various types containing arsenic, tin and mercury. The poison was supposed to bring out the poisonous disease based on the principle that "like-minded people attract". Extravagant ingredients – such as horse hoof filings, coral, crab eyes and claws, scorpion oil – were used for a poultice to be applied directly on the bubo. In the hospitals, deaths were more frequent than healings and the high number of deaths required rapid burials in mass graves and very deep, to prevent the miasmas produced by the decomposition of the corpses from contaminating the air around the burials.

The plague of 1630, famous for being immortalized by Alessandro Manzoni in the Betrothed and in the History of the infamous column, scourged the major Italian and European cities with particular virulence. Historians agree that the serious economic crisis of the immediately preceding years, accompanied by the drastic drop in births, in turn due to the general state of malnutrition, is the contributing cause. Shortly before, a terrible famine had in fact hit Northern Italy and the villages were stormed by vagrants and beggars. Some demographers consider the plague of 1630 as a sort of watershed in the history of Italy: in fact, while the preceding epidemics had substantially spared the countryside and decimated the poorest sections of the urban population, it raged indiscriminately throughout the peninsula and in all social classes. Manufacturing production was severely damaged as a result, precisely in a phase of fierce competition with the Netherlands and the northern European economies.

The main sanitation measures to contain pestilences had been developed in England by the Royal College of Physicans since 1578: purifying the air, infected objects and houses with perfumes and fumigations; change clothes and linens frequently; thoroughly wash or burn clothes used for a long time; use rue and absinthe in large doses. In 1665 the plague devastated London, which then had half a million inhabitants. The deaths were one hundred thousand, despite the measures implemented: cleaning of the drains, removal of bad smells coming from the residues of corn and fish and from the tanning; ban on displaying and selling used clothes. The poorest citizens remained in the city, the wealthiest took refuge in the countryside with stocks of fumigants based on rare and expensive ingredients composed of sulfur, saltpetre, amber, hops, pepper and incense.

That of 1665 was the last plague in London; then, for unknown reasons, the killer disappeared from English soil. Perhaps the great fire of the metropolis in September 1666 contributed. The city was rebuilt in brick and stone and equipped with an efficient sewage system. With the seventeenth century the great plagues ended, except for a devastating queue in Marseille in 1720.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/noterelle-storiche-sulle-pestilenze-in-europa/ on Sat, 14 Nov 2020 06:20:37 +0000.