The origins of proportionality in Europe

Michael Magno's Notepad

While Beppe Grillo reconfirms his old love for direct democracy and the draw of the elected, after the constitutional referendum the lost sheep of the new electoral law continues to wander in the labyrinth of the majority or proportional system, of the access or exclusion clauses, of the nominated from above or of the anointed ones from below. However, as Gianfranco Pasquino observed, according to a partisan publication to say the least, Italians would have proportional representation in their genetic code. Nothing more false. On the contrary, in the DNA of our paternal ancestors (the maternal ones did not enjoy the right to vote) there is the double-round majority system in single-member constituencies, which characterized the elections held from 1861 to 1911. affluent classes, the victory of one candidate instead of another was not at the time a reason for memorable clashes ( Translating votes into seats , Lectio brevis at the Accademia dei Lincei, 11 March 2016).

The scene changed drastically when society became mass, and organizational and ideological factors took precedence over those personal factors (lineage, wealth, education) that guaranteed the election of the most prominent or politically capable notables. Moreover, the real reasons for the proportionalist turn in Italy are too often overlooked. At the beginning of the twentieth century Giovanni Giolitti accepted it fearing the advance of the socialists and the popular, who could cut the grass under the feet of liberal candidates in single-member colleges. The introduction of the proportional, first proposed together with an enlargement of the suffrage, then applied for the first time in the 1919 elections, had therefore an evident and strong defensive intent.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, even in Great Britain the rise of Labor was undermining the power of the conservatives and liberals, who until then had shared it by alternating with the government of the country. After some hesitation, however, the conservatives rejected any reform of the "plurality" system (single-member one-shift). Nonetheless, once the liberal crisis precipitated between 1910 and 1928, in the following decades the electoral reform was repeatedly agitated against the single-turn majority, which rewarded conservatives and Labor with absolute majorities of seats, very rarely able to reach 40. percent of the vote. Only in 2011 was a referendum called for the transition to a system called "alternative voting", which was also a majority vote system. He was soundly rejected by the subjects of Queen Elizabeth.

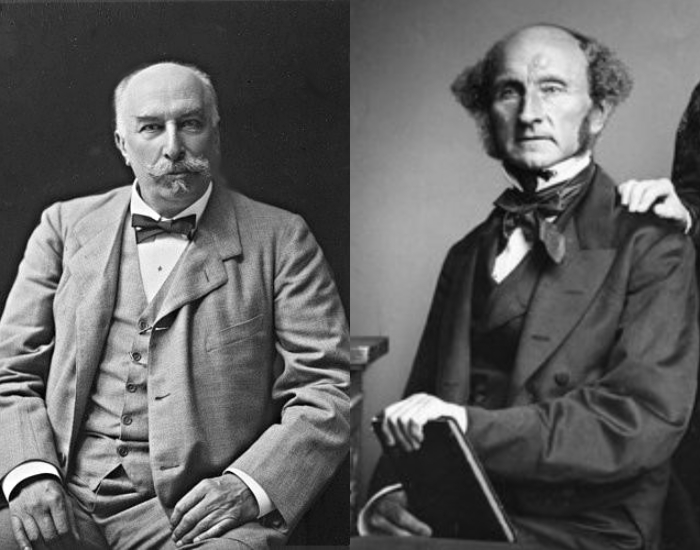

Subject of Queen Victoria was instead one of the most aggressive apostles of proportional representation, John Stuart Mill: “Man for man, the minority must be represented in full as it happens for the majority. If this is lacking, the government does not postulate equality, but privilege and inequality ”. When the Pentonville philosopher published his most famous book, Considerations on Representative Government (1861), proportionalism was still in its infancy and had known a complete theory only a few years ago, thanks to the English lawyer Thomas Hare, who had published in 1859 the first edition of the Treatise on the Election of Representatives, Parliamentary and Municipal.

Mill and Hare had a clear perception of the problems posed by the industrial revolution and subsequent urbanization. Two phenomena that had caused a real demographic earthquake, now in stark contrast with the rules of the House of Commons, where the "rotten boroughs" (putrid villages) continued to have the right to elect deputies, small rural centers controlled by the landed aristocracy, to the detriment of large cities like Birmingham and Manchester, without representation (the most famous of the rotten villages, Old Sarum, with six voters elected two parliamentarians). Larger rural centers were instead the "pocket boroughs", so called because they literally "in the pockets" of the landowners who, thanks also to the open vote, had no difficulty in having their proteges elected.

The first draft reform of the British electoral system was presented by Whigs and radicals in March 1831, under the impetus of the Chartist movement and the French July. It became a law (Act) in 1832. It abolished rotten boroughs, established uniform voting requirements for the "boroughs" and guaranteed representation to the most populous cities. In the second half of the century, three Acts (in 1867, 1872 and 1884) introduced the secret ballot and lowered the capital requirements of suffrage, extending it to the city bourgeoisie and the first nuclei of the urban proletariat. Finally, the Redistribution of Seats Act (1885) redesigned the boundaries of the counties (which had remained unchanged since 1660), removing from the Crown the right to set the number of parliamentarians at its discretion, and generalized the institution of the single-member constituency. Thus was sanctioned that majority principle in the crosshairs of the proponents of the proportional method, who preached the need – which became the banner of their battle – to distinguish between the deliberative vote of Parliament (which obviously required a majority) and elective vote (which instead required a its proportional composition).

As Daniele Maglie underlined in a golden essay, one of the dogmas of the French Revolution was precisely the proportional ( The origins of the proportionalist movement in Italy and Europe, Department of Political Sciences of the Roma Tre University, July 2014, available in pdf). Two of its protagonists, the abbot Sieyés and the count of Mirabeau, had been the most vigorous standard bearers. However, the Constitution of 1791 inaugurated a complicated mechanism, according to which the primary assemblies of citizens nominated the voters, who in turn would have chosen the 745 members of the legislative body by an absolute majority. Not a proportional system, in short, but an all-round “majority” (double shift). The Jacobin Constitution preserved this majority system, albeit corrected with direct election and universal male suffrage. Moreover, his tutelary deity, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, starting from John Locke believed that “il n'y a qu'une seule loi qui par sa nature exige un consentment unanimo. C'est le pacte social […] ”. Furthermore, “la voix du plus grand nombre oblige toujours tous les autres; c'est une suite du contract même… ”( Du contract social , 1762).

On the other hand, the Genevan philosopher tries to overcome the contradiction he perceives in these propositions by explaining why, in undergoing choices in which he has not participated, the citizen is no less free. And it surpasses it on the basis of the famous sophism that identifies the general will and the will of each one, by virtue of which even the minority in reality "wants" the general will and, therefore, agrees to what the majority decides (if it votes in a different way, it say he is mistaken). In this way, the division between majority and minority becomes apparent. In the Rousseauian conception, therefore, any concern for the rights of minorities is completely absent. And even if Rousseau himself proposed a reasonable temperament of majority rule, the fact remains that the conceptual foundations of his theory will be used to justify first Jacobin rigor and then democratic radicalism.

But it was indeed a fellow citizen of Rousseau, Ernest Naville (1816-1909), who became the noble father of the proportionalist doctrine in nineteenth-century Europe. Born in Chancy from a bourgeois family of conservative traditions, he graduated in theology in Geneva where he was consecrated pastor. A convinced spiritualist in an era dominated by positivism, deeply shaken by the religious conflicts between Catholics and Protestants and by the civil war following the dissolution in 1847 of the Sonderbund (the separatist league of the seven Catholic Cantons), he began to scrupulously analyze as a social scientist – " observer, supposer, vérifier ”, was his motto – the institutional architecture of Giovanni Calvino's homeland and the tensions to which it was subjected due to a majority electoral law that excluded minorities from the Grand Council.

Given the deafness of the cantonal authorities to any request for reform of the electoral system, Naville founded “La Réformiste”, an association destined to become a model for all the proportionalists of the Old Continent. It was inspired by a similar association created in Italy in 1872, whose promoter committee included – among others – Terenzio Mamiani, Marco Minghetti, Attilio Brunialti, Luigi Luzzatti. Naville, however, will have to wait twenty-seven years to see his tireless reform initiative rewarded. On 6 July 1892, in fact, the Grand Council abrogated the majority vote, replacing it with the proportional one. A month later, the Genevans were called upon to comment on the constitutional innovation. Its approval was not a plebiscite, but it nevertheless marked a watershed in European electoral history.

Belgium, like Switzerland, was (and is) crossed by deep divisions of an ethnic and sectarian nature. The question of the representation of minorities thus soon became crucial. Shortly after its baptism as an autonomous state entity (1830), a lively debate arose on the extension of suffrage and on the distortions of the majority system in force. Until in 1878 a mathematician and jurist, Victor D'Hondt, published a pamphlet that would give a sudden acceleration to the story of proportionality throughout the Old Continent, La Représentation Proportionelle des Partis par un Électeur. Without going into its technicalities, a method was described (in Italy it will be used to determine the distribution of seats in the provinces and in the Senate) which marked the definitive separation between personal representation and party representation. On May 27, 1900 the Belgian Parliament, for the first time in Europe, was renewed with this system.

From that moment on, utopia became a reality. A reality moreover easily exportable in a historical phase in which the mass parties were preparing to supplant the old notabilary formations. After the Belgian reform, practically all European states – except England – adopted a proportional system in the course of twenty years. An unstoppable process, which even Weimar Germany (1918-1939) did not escape. On the other hand, the strongest party, namely the Social Democrats, certainly could not repudiate their struggles for the widest possible political representation in support of post-imperial democracy. Too often accused of responsibilities not hers in the rise of Nazism and the collapse of the Republic, the German proportional law applied in large circumscriptions, moreover with recovery of remains, did not provide for any minimum threshold for access to the Reichstag.

It would be wrong to say that that law in itself encouraged, if not actually produced, party fragmentation. In any case, the number of parties went from 14 in 1920 to 28 in 1932. Giovanni Sartori argued that the proportional is the photograph of the fragmentation existing in the parties. Perhaps it is more correct to say that proportional laws without any threshold of access (or with very low thresholds) favor fragmentation, as the Italian case demonstrates ad libitum. Who knows if our political leaders will be able to take into account the lessons of history. I doubt it. Because, as Gramsci said, it has always had bad students.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/le-origini-del-proporzionalismo-in-europa/ on Sat, 26 Sep 2020 05:23:48 +0000.