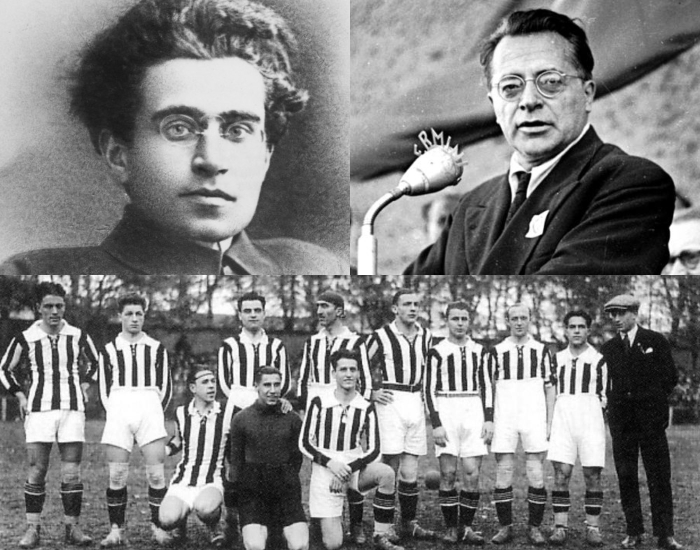

Gramsci and Togliatti, the revolution and Juventus

The Notepad of Michael the Great

The anecdote is well known. While he was making his speech during a meeting at Botteghe Oscure, an enthusiastic Pietro Secchia is abruptly interrupted by Palmiro Togliatti who asks him: "What did Juventus do yesterday?". The head of the PCI organization, visibly embarrassed, is silent. Then the Best apostrophes him, coldly: "And you pretend to make the revolution without knowing the results of Juve?". How to say, without knowing the moods of the people you ask to rise up? The head of the Communist Party, a fan of the "Old Lady", thus reproached his deputy for ignoring the importance of a mass phenomenon such as football, elected by fascism as a national sport, capable of influencing the mentality and customs of the popular classes.

This was a point that had already captured Antonio Gramsci's attention at the dawn of the twentieth century. Proof of this is “The foot-ball and the scopone”, a famous article published on August 16, 1918 in the Avanti !. On the other hand, as Guido Liguori pointed out, the Turin in which the Sardinian thinker lived had been, together with Genoa, the cradle of football in Italy (Una palla di cartapesta, in “Lancillotto e Nausica, XIV, 2-3, 1997). The first football club was born in Turin between 1887 and 1890; also in the Savoy city, in 1898, the Italian Football Federation was founded, which had its first headquarters there. Again in Turin, in the same year, in a single day (8 May) the first championship was played between three Turin teams (Internazionale, Gymnastics Turin and FC Torinese) and Genoa. And finally in Turin, in 1897, two years before Fiat, Juventus was born by some pupils of that D'Azeglio high school also frequented by friends and teachers of Gramsci. Juventus which in 1905 had won its first title.

When Gramsci is interested in football, therefore, he does it from a privileged position, at a time when the ball was conquering crowds of fans, so much so as to allow the creation of a league of amateur teams, with hundreds of members throughout the peninsula. In short, football was taking on a mass dimension that was impossible to ignore. From the beginning of his article, the future founder of the PCI tackles the question that is most close to his heart: “Italians do not love sport; Italians prefer the scopone to sport. In the open air they prefer the seclusion in a tavern-café, to movement the quiet around the table ”. And, after scolding his compatriots for their sedentary lifestyle, he celebrates football as a metaphor for liberal society: "Observe a football match: it is a model of individualistic society: initiative is exercised, but it is defined by law; the personalities are distinguished hierarchically, but the distinction is made not by career, but by specific ability; there is movement, competition, struggle, but they are governed by an unwritten law, which is called 'loyalty', and is continually remembered by the presence of the referee. Open landscape, free circulation of air, healthy lungs, strong muscles, always tense for action ”.

These considerations are in line with the proletarian pedagogy of the time, which advised workers not to frequent smoke-filled taverns and instead invited them to practice outdoor sports – as well as hiking and cycling – to safeguard their health. , severely tested by the infernal conditions of factory work. On the other hand, these are considerations that clearly allude to the British reality, a liberal reality par excellence and a land that gave birth to modern football, codifying its behaviors and rules. It is known how the young Gramsci – at least up to the study of the classics of Marxism – nourished his rebellism, in the wake of Gaetano Salvemini and the socialists on the left, with a strong free-trade streak, in which he saw a lever to undermine the suffocating bloc interests that protectionism and the Giolitti state protected at the expense of the most backward areas of the country. In fact, customs duties had seriously impoverished the populations of the South, who were in fact forbidden to buy products from abroad that cost much less than those produced in the North. These were the years in which a vast intellectual movement, led by men such as Croce, Gentile, Prezzolini, Papini, shook the national culture by opposing the prevailing evolutionary positivism. As he wrote later, speaking of Umberto Cosmo, an Italianist and Dante scholar, of whom he had been a student at the University and who had taught at the D'Azeglio high school which also occupies an important place in the history of our football, "I it seemed (…) that we found ourselves in a common ground which was this: we participated in whole or in part in the movement of moral and intellectual reform promoted in Italy by Benedetto Croce ”. It is not surprising, therefore, that he saw liberal England as a model of an open and dynamic economy. And that he saw in football the somewhat vitalistic exaltation of forces that do not try to win with the deception and corruption so typical of the Giolitti system of power, but that compete honestly to overcome the opponent.

A completely different thing, however, is “a game of scopone. Enclosure, smoke, artificial light. Screams, punches on the table and often on the face of the opponent or … of the accomplice. Perverse brain work (!). Mutual distrust. Secret diplomacy. Marked cards. Legs and toes strategy. A law? Where is the law that must be respected? It varies from place to place, it has different traditions, it is a continuous occasion for contestation and quarrels. The game of scopone has often resulted in a corpse and a few bruised skulls. It has never been read that a football game has ever ended in this way ”. This last notation is the one that most catches the eye today for its imprecision, and not only in the light of the most recent flaws in the football world. Because Gramsci, if he had been a deeper connoisseur of football history, would have known not only of the many episodes of violence that have already occurred in the United Kingdom, but also that the first Italian championship had been the scene of two violent brawls between the supporters of the teams in the field. Moreover, as the chronicles of the Republican age would have taken charge of showing, even in football there would have been ample space for "secret diplomacy" and "marked cards", or pastette and cheating. Gramsci, however, was interested in something else. Football and scopone for him symbolized two different ways of conceiving modernity: the first expression of modern capitalist society, the second fruit of a static, patronizing and maramalda society.

As he explains in his article: “The economic-political structure of states is also reflected in these marginal activities of men. Sport is a widespread activity of societies in which the economic individualism of the capitalist regime has transformed customs, aroused, alongside economic and political freedom, also the spiritual freedom and tolerance of the opposition. The scopone is the form of sport of economically, politically and spiritually backward societies, where the form of civil coexistence is characterized by the police confidant, the policeman in plain clothes, the anonymous letter, the cult of incompetence, careerism (with relative favors and thanks from the deputy). Sport also arouses the concept of fair play in politics. The scopone produces the gentlemen who have the worker who in free discussion dared contradict their thinking to be put at the door of the boss ”.

In this passage, therefore, the scopone is taken as a symbol of Giolitti's Italy, all tricks and deceptions, violation of rules and laws, pure arbitrariness (in the absence of an arbitrator). However, in 1932 Gramsci changed his opinion. In his Miscellanea and notes on the Italian Risorgimento (contained in the Prison Notebooks), he launches a decisive attack on political parties guilty of having favored an "apoliticism of the lower classes". This undemocratic apoliticism and enemy of freedom, was the result "of the roughly the physiognomy of traditional parties, the roughly of programs and ideologies" that had allowed the tenacious rooting of "parochialism and other tendencies that are usually cataloged as manifestations of such a called a quarrelsome and partisan spirit ". Such "primitivism has been overtaken by the progress of civilization", but "this has happened due to the spread of a certain party political life that widened the intellectual and moral interests of the people". With this virtuous circle fading, municipal schemes “have been reborn, for example through sport and sports competitions, in often wild and bloody forms”.

Fifteen years after the article on Avanti !, Gramsci was now pointing his finger at the degeneration of stadium support, which emerged clearly with the advent of fascism and the consequent nationalization of sport, extinguishing political and trade union commitment. The reverse of Gramsci – part of a wider opposition to the Mussolini regime that will pay with imprisonment – was not isolated and found an illustrious side precisely in Benedetto Croce, in those same years ready to define sport, in his History of Europe in the nineteenth century, a real "deviation of the spirit". This reverse on the stock was preceded by a rehabilitation of the scopone matured during his imprisonment. Arrested on November 8, 1926, in open violation of his parliamentary immunity, and initially confined to Ustica where he will remain from December 7 to January 20 of the following year, the communist leader will be part of a large colony of politicians. Forced to spend most of the day in forced idleness, they had to work hard to pass the time, far from their families and civil life. In a letter to his wife Giulia (January 15, 1927), Gramsci confesses: “At home, in the evening, we play cards. I had never played until now; Bordiga assures me that I have what it takes to become a good scientific scopone player ”.

Moreover, if the latter after the Liberation had among his innumerable followers, alongside prestigious intellectuals such as Pirandello and Mario Soldati, important politicians (among others, Pertini, Andreotti, Berlinguer, La Malfa, Lama, Pajetta , Ciampi), there must be a reason. Not only because, unlike what Gramsci believed, of all the games of memory and reasoning it is perhaps the most compelling and complex: “ingenious and virtuous”, as Paolo Monelli defined it. But because, as Chitarella's last rule states: "[…] philosophia scoponis est in longiquum spectare et ultra lucrum proximum remotos exitus consider" (the philosophy of the scopone lies in looking and considering, beyond the immediate advantage, the result the final).

If you are learned, teach, if you are holy, pray, if you are prudent, govern, Saint Paul warned. In this sense, the scientific scopone, suggested Oscar Mammì, his eminent theorist, should be taught in the schools of good politics as a compulsory subject. Unfortunately – he concluded with the irony that was congenial to him – these schools have never been opened. It's true: about Chitarella, the father of the scopone, nothing is known. In a letter dated 25 February 1946 to Croce, the Neapolitan journalist and historian Gino Doria admits to having investigated his mysterious identity, obtaining only the confirmation of an old and meager local tradition, according to which he was a Neapolitan priest who lived in the eighteenth century. But what does it matter? It matters that the century of the Enlightenment has given us not only the sacred principles of 1789 (which have always been violated), but also the forty-four rules of Chitarella (which, on the other hand, can never be violated).

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/gramsci-e-togliatti-la-rivoluzione-e-la-juventus/ on Sat, 25 Sep 2021 05:39:45 +0000.