Kaldor Vs Thatcher. That is, when excesses cause excesses

Keynesian economics would not be the one we know without the work of a real school, the Cambridge school, of economists which developed around the ideas of the great technician of the first half of the 20th century. One of the most active economists, even politically, of this school was Nicholas (or Nikolas) Kaldor, who also had the honor, or the burden, of being able to directly criticize Margaret Thatcher's neoliberal policies.

Given the weight of his figure we will deal with him in two episodes: first the general information, his vision of the economic cycle, which completed the Keyynesian theory, and his clash with Thatcher. Hence his vision on industrial policy and the theme of productivity, which will allow you to better understand the errors of so much economic policy

We will try to make the theory as understandable as possible, and we hope to succeed. Be lenient with our meager abilities

Who was Kaldor

Nicholas Kaldor (1908-1986) was one of the most influential postwar economists. Born in Budapest, Hungary, he moved to Berlin in 1926 to study economics and then to London, where he graduated from the London School of Economics (LSE) in 1930. He was an assistant and then a lecturer at the LSE until 1947, when he became director of the research and planning of the Economic Commission for Europe in Geneva. In 1949 he moved to Cambridge, where he was professor of economics from 1966 to 1975. He was also a consultant to various governments, including British Labor in the 1960s and 1970s, and to international organizations such as the United Nations. He was made a life peer in 1974 as Lord Kaldor of Newnham. A Hungarian who became an English Lord.

Kaldor made original and innovative contributions to many fields of economics, including growth theory, income distribution, taxation, international trade, capital theory, and the history of economic thought. He was one of the leading exponents of the post-Keynesian school, which set out to develop and broaden the ideas of John Maynard Keynes on the determination of the level of employment and income in a monetary economy. He was also a sharp critic of the neoclassical theory of economic equilibrium and monetarist policies inspired by the Chicago School.

Kaldor and the theory of the business cycle

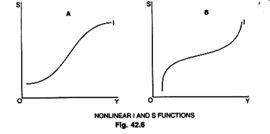

Pure Keynesian theory, with a linear view of the investment and savings curve in the IS system, did not provide a sufficient explanation for the presence of business cycles. Right here Kaldor intervened with a completely different view that assumed a non-linear curve, based on empirical observations.

Kaldor's business cycle theory is based on the Keynesian analysis of saving and investment. Kaldor shows that the cycle is the result of the pressures that push the economy towards equality of anticipated saving (ex-ante) and anticipated investment. Indeed, it is the difference between ex-ante saving and ex-ante investment which induces a chain of reactions until the equilibrium level of income is restored.

Kaldor introduces a key variable that plays an important role in the cyclical change of saving and investment: capital (K) in the economy. Saving is a direct function of capital: for any level of income, the higher the capital, the higher the savings. Conversely, investment is an inverse function of capital: for any given level of income, the higher the capital, the lower the investment.

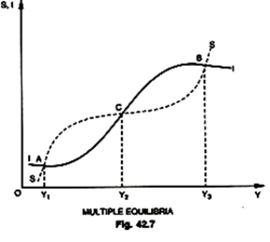

Kaldor assumes that the saving and investment functions are nonlinear, that is, that they have a curved rather than a straight shape. This implies that there are different points of intersection between the two curves, which correspond to different equilibrium levels of income. However, not all of these points are stable: some are unstable equilibrium points, where a small deviation from the equilibrium level causes the difference between saving and investment to widen and thus income to change in one direction or the other.

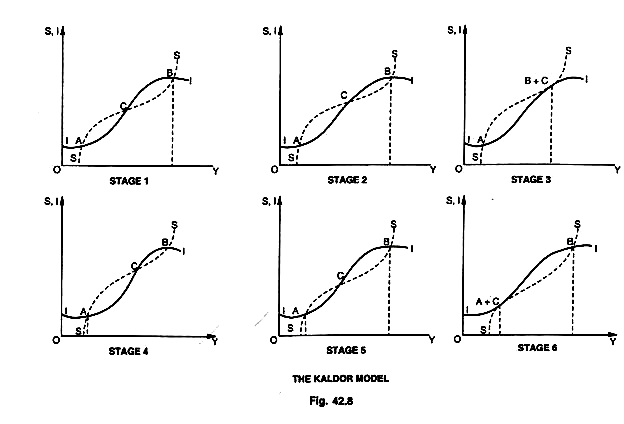

Kaldor identifies six phases of the business cycle, which follow each other alternately:

- Expansion: income is below the stable equilibrium level and investment is higher than saving. This generates an increase in aggregate demand and therefore in income through the Keynesian multiplier.

- Boom: income reaches stable equilibrium level and investment equals saving. This is the phase of maximum prosperity of the economy.

- Overheating: income exceeds the stable equilibrium level and investment is less than saving. This generates excessive aggregate demand which causes inflation and makes investments less profitable.

- Contraction: income decreases towards the unstable equilibrium level and investment exceeds saving. This generates a reduction in aggregate demand and therefore in income through the Keynesian multiplier.

- Depression: income reaches the unstable equilibrium level and investment equals saving. This is the least prosperous phase of the economy.

- Recovery: income falls below the unstable equilibrium level and investment is less than saving. This generates insufficient aggregate demand which causes deflation and makes investments more profitable.

The following figure graphically illustrates Kaldor's theory of the business cycle, with the saving (S) and investment (I) curves and the different equilibrium levels of income (Y).

Kaldor's critique of Thatcher's economic policy

First of all, let's put Mrs Thatcher's economic policies in the right historical context: remember that she became prime minister at the end of a long period of Labor governments which had pushed hard towards trade unionism and state intervention in the economy. Public giants, inefficient, were born in the aeronautical, construction, mining and automotive sectors.

This, combined with a series of very heavy sectoral strikes and inflation brought about by the oil crises, at a time when North Sea oil production was only in its infancy (it only became relevant in the late 1970s) led to a wave of fear of economic instability and the destruction of wealth which, in turn, brought Mrs Thatcher to power in 1979.

The excesses of the left led to the government of a non-traditional right, but hyper-liberal and close to the positions of the Chicago School.

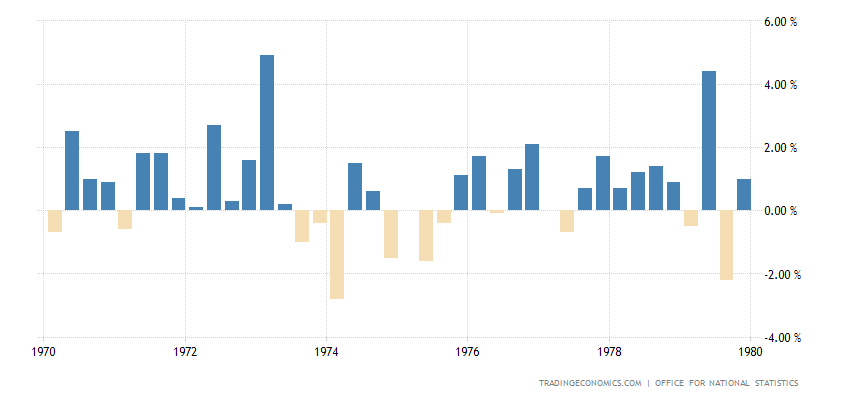

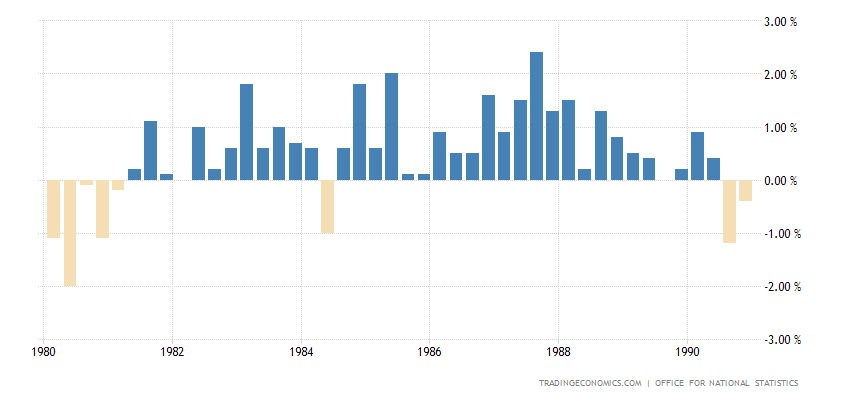

The reality, from a GDP standpoint, the 1970s data wasn't so terrible

And the eighties opened with a harsh recession. Mrs Thatcher probably would not have survived politically without the Falklands War.

Employment was always below 6% in the 1970s, and doubled in the 1980s.

Kaldor's critique of Thatcherism is based on his view of the economy as a dynamic and unbalanced system, in which growth depends on effective demand and income distribution. Kaldor rejects the idea that economic policy should focus on controlling the money supply and balancing the public budget, as the monetarists of the Chicago school argued. On the contrary, he argues that economic policy must stimulate aggregate demand, in particular that destined for manufacturing production, which has positive effects on productivity, innovation and employment.

Kaldor was a great connoisseur and supporter of industrial politics. He considered it the basis of the economy, so much so that in the 1960s he suggested legislation which privileged, for tax purposes, jobs in industrial production rather than in services, to keep British industry competitive.

Kaldor delivered several speeches in the House of Lords between 1979 and 1982, in which he attacked the economic policy of the Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher, based on monetarist ideology and the reduction of public spending. He accused Thatcher of adopting a strategy for inequality, of causing a severe recession, of destroying British manufacturing and of ignoring the lessons of economic history. He defined the economic consequences of Thatcher as "the greatest catastrophe that has ever occurred in peacetime" 1 . You can read some of her speeches in the book “The Economic Consequences of Mrs. Thatcher: Speeches in the House of Lords, 1979-1982”, edited by Nick Butle

According to Kaldor, Thatcher was destroying Britain's manufacturing base and wiping out industrial know-how that simply could not be recreated. He never spoke of deindustrialization, a new term at the time, but he carefully explained its consequences in his last speeches.

Who knows what he would have said seeing the current policies of the EU and the deindustrialization we are experiencing now

Thanks to our Telegram channel you can stay updated on the publication of new articles from Economic Scenarios.

The article Kaldor Vs Thatcher. Or when excesses cause excesses comes from Economic Scenarios .

This is a machine translation of a post published on Scenari Economici at the URL https://scenarieconomici.it/kaldor-vs-thatcher-ovvero-quando-gli-eccessi-causano-eccessi/ on Wed, 30 Aug 2023 12:23:47 +0000.