Submarine cables: neither China nor the USA adequately protect them

Future wars, or even acts of terrorism, could one day involve undersea communications structures, such as fiber-optic cables for data transmission. Yet neither China, nor the USA, nor supranational organizations have adopted the legislative instruments necessary for their adequate protection

In May 2018, the World Bank opened the tender to “any eligible company from any country” for a $72.6 million undersea fiber-optic cable system that sought to improve the internet infrastructure of three island nations of the Pacific: Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), Kiribati and Nauru (World Bank, May 1, 2018).

Companies such as Japan's NEC, France's Alcatel Submarine Networks and China's HMN Tech have entered the procurement frenzy. HMN Tech, formerly known as Huawei Marine Networks, bid 20% lower than its competitors and appeared to be well positioned to win. But in February 2021, the World Bank canceled the bidding process altogether, invalidating all participants as "non-compliant" with the "required conditions" (Nikkei Asia, March 18, 2021). The tender ended without an award.

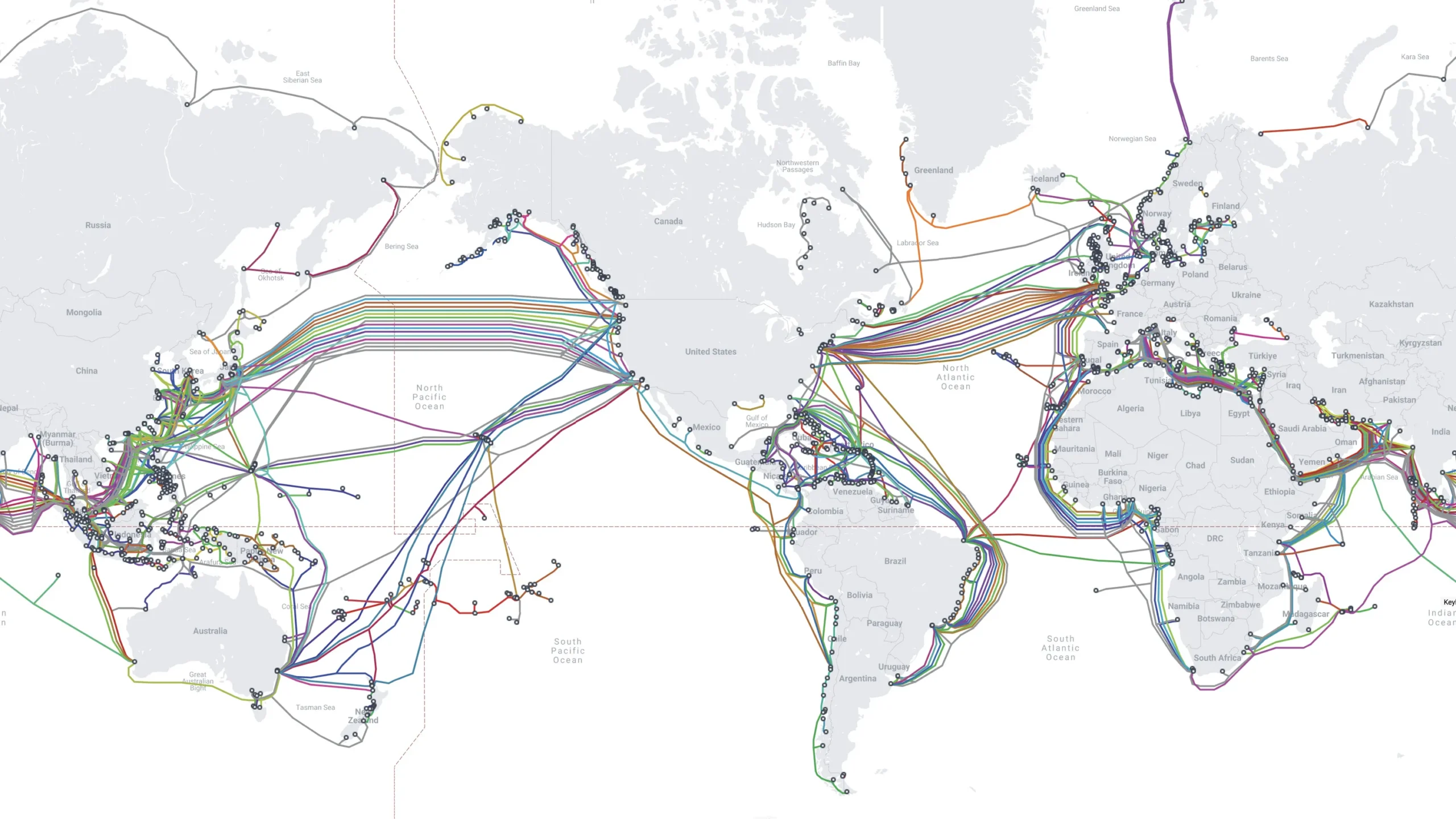

Later, it was revealed that the World Bank's decision was largely influenced by diplomatic pressure from the United States. In July 2020, a memo from the US State Department warned Micronesian officials that HMN Tech's involvement in laying the cable posed a security risk from espionage by the Chinese government. In December 2021, three years after the World Bank started the bidding process, the US, Australia and Japan announced they would finance a cable along the same route. Production work on the 1,398-mile-long East Micronesia cable system officially began in June. The story of the East Micronesian cable system is just one example of intensifying competition between Washington and Beijing for influence over the 800,000-mile-long undersea cable ecosystem.

These cables are crucial to the world economy and international communications: 99% of intercontinental data traffic, the SWIFT financial messaging network which transfers $5 trillion worldwide daily, diplomatic cables and military orders pass through these cables (Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, accessed August 3). However, the prominence of these submarine fiber optic systems also makes them attractive targets for sabotage and espionage. The US Office of the Director of National Intelligence has labeled cyberattacks against cable landing stations a "high risk" to national security.

Policy makers are increasingly viewing cables as critical infrastructure that needs to be protected. But wondering whether a particular cable is owned by China Telecom or supplied by HMN Tech is not enough to guarantee the security of a cable from foreign and domestic threats. Another important question is whether countries' legal regimes provide sufficient protection for undersea lines of communication in their waters. This article will analyze US and Chinese government regimes, assessing whether their domestic legal frameworks adequately deter against deliberate damage, comply with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and stipulate flexible policies to facilitate rapid remediation. in case of damage. On every metric, both Beijing and Washington fall slightly behind, albeit for different reasons.

The punishment does not fit the crime

The legal frameworks governing submarine cable protection in the United States and China each face a distinct set of challenges. In the case of the United States, the legal regime is hampered by outdated and inadequate domestic legislation to protect its submarine cables. Conversely, while the PRC has relatively modern national laws, the country's governance suffers from insufficient enforcement mechanisms. There are rules, but the implementing bodies do not use them adequately.

The most recent U.S. legislation to protect against submarine cable sabotage dates back to the Submarine Cable Act of 1888. Under 47 US Code Chapter 2, breaking a cable carries a maximum two-year prison sentence and a $5,000 fine (Code of the United States, consulted in August 3). This penalty offers little deterrence against potential cable saboteurs and cannot compensate for the cost of repairs, which average between $1 million and $3 million (International Committee on Cable Protection, consulted Aug. 3).

On the other hand, China does not have a solid track record of enforcing its laws. Under the "Regulation on the Protection of Submarine Cable Pipelines", Beijing imposes different fines depending on the type of criminal act. If a cable operator intentionally damages submarine cables or fails to take effective measures to ensure their protection, he will be ordered to cease operations and subject to a maximum fine of RMB 10,000 ($1,385) (State Council, January 9, 2004). Cable operators who lay submarine cables and pipelines without proper authorization face the harshest penalty, incurring a fine of RMB 200,000 ($27,700) (State Council, August 26, 1992). Despite these relatively robust measures, Beijing's more modern legal framework has not achieved much success due to a weak enforcement record; between 2008 and 2015, China experienced an average of 26 cable failures per year, the most of any nation. .

Inconsistencies with UNCLOS

Both the United States and China also have internal regulations that are inconsistent with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the international agreement often described as the "constitution of the oceans." China embraces an overly liberal interpretation of coastal states' rights, while the United States lacks domestic legislation making damaging an underwater cable punishable. Both countries also require cable-laying vessels to obtain permits before commencing operations in their respective waters, which contravenes UNCLOS Article 58.

China makes the delimitation of cable routes conditional on the consent of the coastal state, although the UNCLOS does not allow it. Under Article 79(3), “the delineation of the route for laying such pipelines on the continental shelf is subject to the consent of the coastal State”, and this requirement is not mentioned for submarine cables. This legal distinction reflects the different environmental impacts of a broken cable and a broken pipeline, the latter of which is much less environmentally friendly. According to the "Measures Implemented for Provisions Governing the Laying of Submarine Cables and Pipelines", foreign companies seeking to lay cables and inspect cable routes on China's continental shelf must notify the nation's State Ocean Administration and all the routes must receive the express consent of China (Ministry of Natural Resources, August 26, 1992).

The United States also has domestic laws that are inconsistent with UNCLOS provisions. Although Washington has not ratified the international agreement, US administrations have consistently treated the international treaty and its provisions as customary international law. Article 113 of the UNCLOS requires all states to adopt laws making breaking a submarine cable “intentionally or through negligence” as a punishable offence. As mentioned above, the United States has not updated criminal penalties for cable failures in over 130 years, since the Submarine Cable Act of 1888.

Permits, permits, permits

Both countries impose stringent licensing requirements that go against UNCLOS. Both states' licensing measures highlight their priority for national security considerations, but these regulations do not come without costs. Article 79(2) of UNCLOS authorizes states to take “reasonable measures” in the exploration of the continental shelf and exploitation of its natural resources, although such measures should not “prevent the laying or maintenance of such cables or pipelines” (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982). While states with licensing requirements might argue that they are necessary to ensure foreign cable ships are not engaged in potentially harmful activities, the UNCLOS legal text explicitly states that this remains outside the scope of their jurisdiction.

The licensing process in the United States is particularly complex. Under the Cable Landing License Act of 1921, all submarine cable operators must acquire a license from the FCC (FCC, accessed Aug. 3). For significantly foreign-owned cables – or cables connecting the United States with foreign landing points – applications must be submitted for consideration by the Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector, formerly known as “Team Telecom” (Federal Register, April 8, 2020). The cables must also receive a federal permit from the Army Corps of Engineers to evaluate its potential impact on the environment and any endangered species. [2] This requirement is precisely at the federal level; often state and local permits must also be obtained. Overall, the combined

licensing processes can take up to two years. A 2016 report prepared by an FCC working group on Improving the Resilience of Subsea Cables urged the US government to streamline its permitting requirements (FCC, June 2016). While many policy makers in Washington recognize the problem posed by such clearance standards, a viable solution remains to be found that sufficiently balances legitimate national security considerations.

In the case of China, cable-laying suppliers must first obtain a non-objection letter from the Chinese military before they can submit a formal application to land fiber-optic systems in Chinese-controlled territories or waters (Nikkei Asia, May 19 ). In the event that a foreign vessel successfully obtains a license and begins any laying and repair work, however, other onerous requirements remain. Foreign vessels must carry their vessel names, call signs and numbers; current locations and previous locations; and satellite telephone numbers to maritime authorities.

Chinese officials have also begun applying for permits to lay cables in its exclusive economic zone, the waters that extend between 12 and 200 nautical miles from a state's coast. This violates Article 58 of UNCLOS, which affirms the right of all States to "navigation, overflight and submarine cable and pipeline-laying and other internationally lawful uses of the sea connected with these freedoms" in the exclusive economic zone. In addition, Beijing reportedly has a lengthy approval process for cable projects within its "nine-dash line," a broad claim over much of the South China Sea that was rejected by an international tribunal in the United States. Hague in 2016.

Such bureaucratic requirements can significantly hinder the maintenance of broken cables. Between 2005 and 2009, there were 19 cable failures caused by fishing vessels in China's EEZ in the East China Sea, and repairs were delayed for a couple of weeks due to Beijing's requirements (Submarine Cables: The Handbook of Law and Policy, 2014). China is unlikely to lift such requirements in the foreseeable future. The China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, part of the influential Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, released a white paper in 2018 that recommended establishing a security review process for foreign enterprises aiming to participate in the undersea cable construction environment (China Academy of Telecommunications Research of MIIT, August 2018).

Beijing's cumbersome permitting processes have caused some multinationals to rethink plans to lay submarine Internet cables crossing the South China Sea. Examples include the Meta-supported Echo and Bifrost submarine cables, which are scheduled for completion in 2024. Meta aims to establish the first trans-Pacific cables blazing a new route across the Java Sea (Meta, Mar. 28, 2021). By the end of 2024, a consortium of companies including Meta, Google and Japan's NTT aims to complete Apricot, a 7,439-mile cable crossing Philippine and Indonesian waters. An executive involved in cable projects noted that "over the past two or three years, we have struggled with obtaining permits, particularly for territorial waters claimed by China" (Nikkei Asia, May 19). For many companies, navigating China's regulatory environment has become a major challenge for implementing cable routes crossing its declared waters.

Arguably, these clearance measures could be relevant to safeguard national security interests, especially given the sensitivity of critical infrastructure such as undersea cables. But such laws require difficult compromises. Current regulations drive up costs, slow down installations, and can consequently delay repairs to much-needed Internet access. These policies contradict the recommendations of the International Cable Protection Committee, an international non-profit organization that promotes the protection of the world's submarine cables. [3]

Conclusion

The United States and China are not alone in the need to modernize their regulatory arrangements for submarine cables. The same goes for the UNCLOS framework, which still fails to address several critical issues. For example, deliberate attack

Cables on cables that lie outside territorial seas are unlikely to constitute crimes under international law. Furthermore, coastal states have no legal obligation to adopt laws protecting submarine cables in their territorial seas. Yet these infrastructures are essential to modern society.

If UNCLOS does not update its cable governance regulations to ensure adequate national security protections, states will take their own steps to do so, and the trend towards a fragmented undersea cable landscape is likely to persist. Last March, the US House of Representatives passed the Undersea Cable Control Act, which would require the White House to develop a strategy to prevent "foreign adversaries" from acquiring American-made assets and technology used in the development of submarine cables. , as well as making agreements with allies and partners to do the same (US Congress, accessed Aug. 3).

Domestic regulations in the United States and China are particularly significant given both countries' importance to the international submarine cable market. State-owned China Telecom has a network of 33 submarine cables connecting 72 countries, and the United States boasts 88 FCC-licensed systems of the total 400 submarine cables worldwide (China Telecom Americas, accessed June 29; Submarine Networks, accessed 3 August). As policy makers in both capitals begin to analyse, review and update their respective legal regimes, submarine cable regulatory frameworks will remain a critical space to monitor.

Taken from The Jamestown Foundation

Thanks to our Telegram channel you can stay updated on the publication of new articles from Economic Scenarios.

The article Submarine cables: neither China nor the USA adequately protect them comes from Scenari Economics .

This is a machine translation of a post published on Scenari Economici at the URL https://scenarieconomici.it/cavi-sottomarini-ne-la-cina-ne-gli-usa-li-tutelano-adeguatamente/ on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:00:11 +0000.