Croatia, Greece, Italy (in alphabetical order)

Who won the Thirty Years War (which is the war that was so called because it lasted thirty years, from 1618 to 1648)? The answer shouldn't be very simple, so much so that even the source of sources hesitates to give it clearly, probably because it wouldn't make sense to do so, but in extreme synthesis it seems to be able to conclude that France and Sweden came out as winners, and a little ' reduced to " the emperor ". Does this mean that France and Sweden have been going from victory to victory for thirty years? Of course not. The legitimate aspiration to self-determination of many European peoples asserted itself (partially) through ups and downs. There was no definitive victory or defeat. We surrendered, rather than to the enemy, to the evidence of having taken an irrational path.

Any passing historian will shudder at the crudeness of these considerations of mine, more or less as happened to me reading certain comments on the previous post, all affected by a basic flaw: faith in (and expectation of) an event palingenetic, of a definitive victory (or defeat, depending on one's point of view). In short, the idea that permeates many religions (including the latest arrival: Science), that an external Deus ex machina will balance the score, relieving us of the burden of daily commitment. Unfortunately, this is not the case, and the idea expressed by many that Croatia's entry into the Eurozone will "finally" destroy the Eurozone (and/or Croatia) is tainted, in addition to this basic naivety, by a series of crude evaluations of orders of magnitude and from an incomprehensible oblivion of recent historical dynamics and of the elementary mechanisms of a financial crisis.

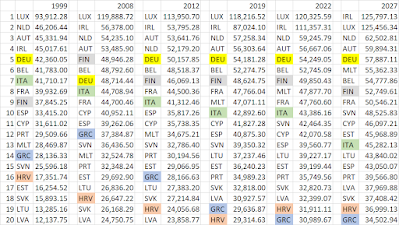

In the meantime, I am providing you with a chart that may be useful to you: the ranking of per capita income in the countries of the current Eurozone, measured in 1999 (the starting year), in 2008 (the year in which the global crisis broke out), in 2012 (the which austerity begins), in 2019 (the last year before the pandemic), in 2022 (the year that has just ended) and in 2027 (the year up to which the forecasts of the International Monetary Fund go, from which the data):

(data are expressed in dollars at 2017 prices and purchasing power parity).

There are many numbers and there would be many things to say, but I would start from the fact that in 1999 Croatia ranked sixteenth in terms of per capita income, and since then it has steadily fallen, arriving in 2019 at twentieth position (the last), except recover one position this year, overtaking Greece which has dropped to last place. A very different path from that of Greece and Finland (to mention two countries whose similarities we immediately highlighted – i.e. since 2012), both of which recovered positions between 1999 and 2008, only to then lose them, in the case of Greece disastrously. Croatia's path, in this sense, is much more similar to ours: we started in seventh position and have steadily dropped, reaching tenth today, and with the prospect of falling to thirteenth in 2027, being overtaken by Slovenia, Cyprus and Estonia .

Now, without prejudice to the trivial fact of nature that in order to "go the way of Greece" (that is, lose eight positions in the ranking of per capita income) Croatia would have to find itself twenty-seventh out of twenty countries (which is obviously impossible!), perhaps we should ask ourselves how the countries that then took the plunge managed to rise in the rankings, and those who have been here for a while already know the answer: by financing their growth with private debt, preferably towards foreign creditors. Now, if we compare what happened in Italy, Greece and Ireland in the nine years before 2008 (therefore from 1999 to 2008) with what happened in Croatia in the nine years before 2021 (therefore from 2012 to 2021) we see that the Croatia was the star of a totally different film:

While, as you should know, in Italy, Greece and Ireland before the crisis we saw private and external debt (understood as the net external debt position) grow (in the case of Ireland, explode) against a decrease or a slight increase in public debt, exactly the opposite has happened in Croatia over the past nine years. Now, of course, the fact that potentially dangerous financial imbalances have not accumulated outside the euro offers no guarantee that this cannot happen inside the euro. But as we know, these imbalances are due to the loss of competitiveness and the need to finance a persistent imbalance in the external accounts with debt (that is, to borrow to pay for the excess of imports over exports). This phenomenon is not visible for now, and as the experience of our previous crises demonstrates (not only that of 2008-2010, but also that of 1992), two elements are needed to arrive at the redde rationem : a long period of accumulation of imbalances ( spring loading), that is, typically, a long period in which the inflation of the candidate country with a bang is higher than that of the countries to which it is pegged; an external shock . These two things are not present in Croatia for now, maybe they never will be (it depends on how the country manages to manage its inflation) and maybe they will come in reverse order (it is probable that the external shock in the form of global financial crisis will present before Croatia has accumulated significant imbalances in the form of significant increases in private and external debt stocks).

As for managing its own inflation, Croatia's looks a little different than, say, Greece, Italy or Ireland fifteen years ago. More than depending on domestic demand pressures, financed by external debt, I believe that in Croatia's case it counts being pegged to the German economy and its relative vulnerability to supply shocks (gas price increases, etc.). So how Croatia fares will largely depend on how Germany fares, while how the inflation differential between Croatia and the other Eurozone countries evolves, at least in the light of current information, does not seem to depend crucially since Croatia's entry into the Eurozone (with the related "easy credit – overspending – pressure on prices – loss of competitiveness – further debt – bang" cycle, i.e. the Frenkel cycle).

I hope I have clarified better because I answered Eleonora like this :

and also why I answered her like this :

I would add a detail to the second answer. Not only was Greece's situation in 2008 very different in terms of dangerous (private) debt than Croatia's in 2021 (and today), but if we go back to the first table we can easily see that Croatia's downward slide in the per capita income ranking between 1999 and 2019 depends on the overtaking by Slovakia (joining the euro in 2009) and the Baltic countries (joining between 2011 and 2015). We can argue about how these countries would have fared had they stayed out, but in Croatia's national political discourse I suppose it was very easy to argue that those countries had fared better because they had entered.

So this further consideration :

by itself it is not "incorrect". Simply, for now Croatia can afford a currency link with which, as I showed you in the previous post, it has been living with for some time. As far as he can afford it, we will see it over time and in many years we should have understood that the variable that will warn us, the canary in the mine (more useful and unfortunate than the cow in the corridor), is the current account balance of the balance of payments ( foreign lending/borrowing).

I don't think you can even put it like this:

If their debt position improved without Monti, it means that they didn't need Monti.

But before entering into the fascinating question of why and how the Croatians have been spared a Planine , we need to answer a preliminary question: if what worries us, in one way or another, is the stability of the Eurozone , the possibility that it will resume a path of growth, that it will recompose the imbalances (made evident in this phase by the widening of the inflation differentials between the various member countries, a sign of dangerous macroeconomic divergence between them), perhaps more than a country that accounts for 0.5% of the GDP of the entire area (Croatia) it would be worth taking a look at the country which accounts for 29.6% of the total.

Or not?

We do it soon.

This is a machine translation of a post (in Italian) written by Alberto Bagnai and published on Goofynomics at the URL https://goofynomics.blogspot.com/2023/01/croazia-grecia-italia-in-ordine.html on Mon, 02 Jan 2023 16:36:00 +0000. Some rights reserved under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 license.