All China’s bluffs on the energy transition

China's cement, steel and petrochemical industries generate more than total European emissions. Enzo Di Giulio's analysis for Energy Magazine

Within the myriad of data that make up the new report of the IEA An Energy Sector Roadmap to Carbon Neutrality in China, there is one that more than any other makes us understand the enormity of the China issue for the climate: the industry of Chinese cement and steel generate more than total European emissions.

This comparison is enough to make us understand that without China any effort from other countries – Europe in the first place – is in vain. And it is good, therefore, that the IEA has dedicated this new study – the first of a series on the climate neutrality trajectories of countries – to the Dragon.

China's cement and steel industries generate more than total European emissions

An unscrupulous summary of the 304 pages of the IEA report could be the following: “it is difficult but it can be done”. A phrase that, after all, is the mantra of the IEA and of the policy makers around the world in the last two years since, ultimately, the esprit du temps is inspired by the aphorism "I prefer to be optimistic and be wrong than pessimistic and to be right".

You can't blame Musk, who recently revived it by recovering it from Einstein: you have to believe in it and work hard, even if what we are facing is a multiplied Everest. And yet, a little inside the numbers we need to look to understand what that year really is.

The IEA Report proposes two scenarios:

– The Announced Pledges Scenario (APS) which reflects the objectives announced by China in 2020 and foresees a peak of emissions before 2030 and zero by 2060;

– The Accelerated Transition Scenario (ATS) which assumes an even faster transition.

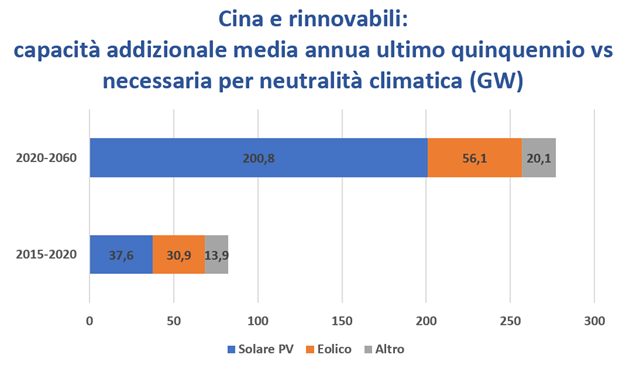

Focusing on ODA, in the search for a synthesis between the being and the having to be of China, perhaps the most significant data is the one that compares the growth of renewables in the period 2015-2020 and that required for climate neutrality in the four decades between 2020 and 2060.

From 82 to 277 additional GW on average per year, the necessary change of pace in renewables

The comparison is summarized in the graph that Timur Gül, Head of the Energy Technology Policy Division of the IEA, showed in the worldwide direct presentation of the Report but which – mysteriously – is not present in the more than three hundred pages of the volume. We have rebuilt it and show it below:

The necessary step change is visible to the naked eye. In aggregate, it is a question of going from 82 additional annual average GW in the last five years to 277 in the future. In other words, the future additional capacity will have to be 3.4 times the past one, which is conspicuous.

A comparison of this kind raises many doubts about the feasibility of the undertaking, but it is also true that the foreseen horizon – four decades – is very long and what appears prohibitive today may very well prove to be achievable tomorrow.

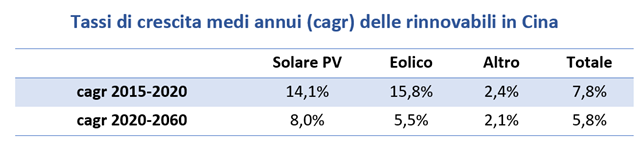

If you look at the average annual growth rates, the undertaking seems less difficult

The overwhelming collapse of the cost of generation from renewable energy testifies how, at times, even the most unlikely scenario can be realized. On the other hand, there is another point of view from which to read these numbers, and it is the one that no longer refers to absolute values but to average annual growth rates (cagr). We report them in the following table.

In this case, the comparison returns an opposite picture compared to the previous one with significantly lower annual average growth rates for the future than in the past.

The intuitive explanation is that as the overall level of accumulated capacity (GW) increases year after year, the same annual additional growth weighs less: hence the lower growth rate.

Faced with this kind of squint in reading the same phenomenon, we can opt for one or the other interpretation and, consequently, join the ranks of pessimists or optimists.

Same phenomenon, different lenses: but in essence, does something really change?

For example, referring to solar, it is undeniable that achieving 14% annual growth when capacity is around 300 GW is much easier than achieving 14% when total capacity is 6 or 7,000 GW. But what about an 8% growth in future capacity: is it worth even more than a 14% achieved in the past? We are in the sphere of uncertainty: beyond any statistical test that we can conceive, the scenario is so long that, ultimately, the interpretation of the phenomenon remains subjective. Therefore, each reader will be able to find their own answer.

Useful information for the formation of a possible opinion – whatever it may be – comes from the analysis of the data relating to investments: how much will it be necessary to spend to boost Chinese renewables?

The estimate made by the IEA is that it is necessary to invest, overall on the supply and demand side, 640 billion dollars in 2030, or more than 10% of the average of the last five years. And then, thereafter, in 2060 the amount would rise to 900 billion dollars.

Not just renewables: climate neutrality also passes from disincentives to fossils

The Agency considers these payments, apparently challenging, entirely feasible for China, so much so that it would go from the current 2.5% of GDP, to 1.6% in 2030 and to 1.1% in 2060. Therefore , the IEA seems to tell us, the money is there and the required leap is not that dramatic. Hence a certain underlying optimism of the Report.

Of course, a lot will depend not only on the flow of investments that will have to stimulate the green sector, but also on the disincentives that will have to curb the carbon ones. On this the Report is rather generic: it does not go beyond general references on the advisability of adopting carbon pricing policies. This seems to be an untouchable key.

Today, on the Chinese ETS – the largest market in the world covering about 40% of the country's energy sector emissions – a tonne of CO 2 costs about $ 7, or one-tenth of the European price.

Chinese carbon pricing is a kind of taboo: CO 2 costs 1/10 that in Europe

This is a market that covers 4.5 billion tons of CO 2 , but which over time is destined to expand to cover the emissions of sectors such as petrochemicals, steel, paper, domestic aviation (an additional 35 % of total emissions).

At the moment, however, the price of CO 2 on this huge market is languishing and is not yet able to convey significant signs of disincentive towards fossil fuels. In other words, it is as if a piece is missing from the IEA Report since the key issue of carbon pricing is not addressed, except in generic terms.

And that this issue is of extreme importance is highlighted by the fact that the Paris Agency has dedicated a certain space to it in the now famous report Net zero by 2050. A Road map for the global energy sector , where it explicitly stated values of price for CO 2 for both rich, emerging and poor countries.

In the IEA Report there is the push for investments, but the brake of carbon pricing is missing

Therefore, in the IEA Report there is the push – investments – but there is no brake – carbon pricing. And the brake is necessary because the transition car goes uphill and without it the gravity inherent in the fossil economy would take it back to the past.

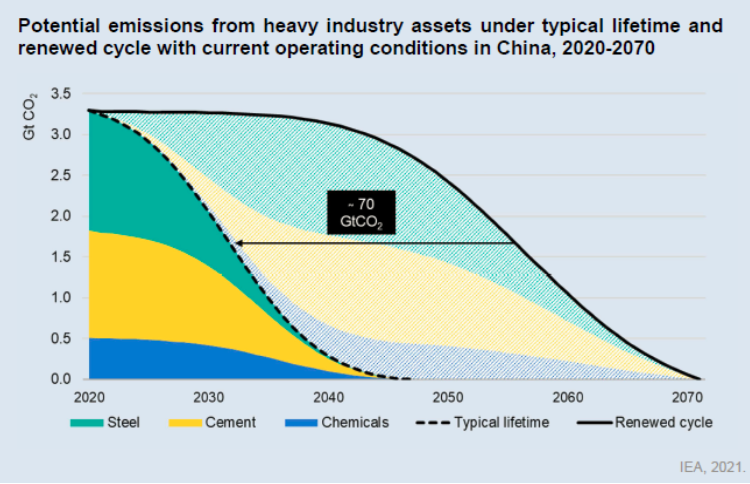

And the country today is literally poised between a past that should be overcome, but which is always there, and a future that must be born. The Paris Agency describes this situation very well by means of a single graph showing the life cycle of the three industries of steel, cement and petrochemicals.

These are three very large and carbon-intensive sectors – China produces half of the world's steel and cement – which, if they remained alive for a further cycle, would emit about 70 billion tons of CO 2 into the atmosphere. That's a volume of carbon that China – and the rest of the world – can't afford.

Is it possible to hinder its genesis without the barrier of carbon pricing?

The question is as valid for China as it is for Europe and the United States. These three economies are committed to achieving carbon neutrality but they are all as if poised in front of the precipice of a new fossil cycle in which they risk falling.

It is not enough to say that the carbon content inherent in a new life cycle based on fossil technologies must not be released into the atmosphere. Purpose does not have the gift of self-realization. Rather, it is necessary to create the conditions so that the new cycle does not set in motion, and the problem cannot be solved with the sole lever of green investments.

It is the market that dictates the rules – in Europe, in America and, to a lesser extent, in China – and therefore it is necessary to create a brake that hinders the animal spirits that inexorably push towards the reproduction of the fossil model.

Europe also needs to do more on carbon pricing

This brake is carbon pricing, but both the IEA report dedicated to China and the recent government interventions activated in Europe in order to calm the inflationary pressure induced by the rise in gas prices, indicate that there is not yet the strength to face this very thorny business.

Energy, today 80% fossil, irrigates the body of the world economy: hindering its flow requires courage and also a mixture of recklessness and technical knowledge, given that the operation has never been done before. At the moment, these three qualities do not appear to abound.

So, what to do? Of course, the path of the environmental standard always remains, a limit on emissions which, in some cases, can become a real ban. When the European Union conjectures to lower, in 2035, the level of carbon emissions from vehicles to zero, it is in fact taking the concept of environmental standards to the extreme until it becomes a real ban.

And it is in this way that the brake of carbon pricing is replaced by the dam of the prohibition that blocks the flow of investments and products towards the old carbon life cycles at the origin. The overhang of the fossil cycle is thus avoided and, apparently, everything was achieved with a simpler operation than carbon pricing.

(Extract from an article published in Energy Magazine)

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/energia/cina-acciaio-cemento-emissioni/ on Sun, 24 Oct 2021 06:37:57 +0000.