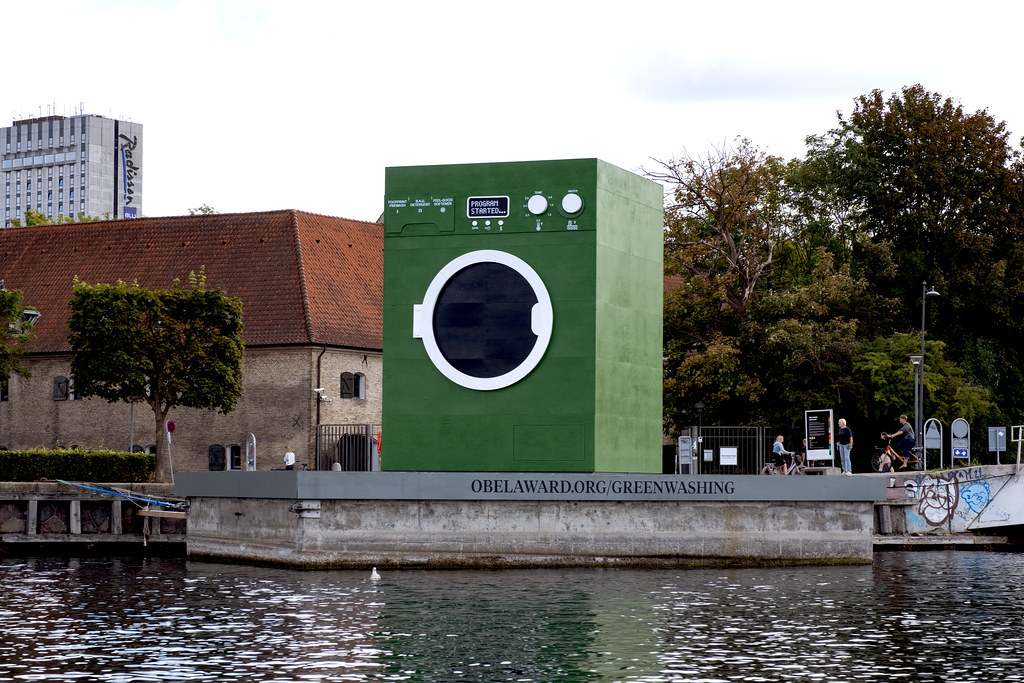

All the bluffs of green finance. Le Monde report

What's right and what's wrong with green finance. The in-depth analysis of the French newspaper Le Monde

“Do you want to completely exclude fossil fuels from your investments?”. These are the questions that banks asked their customers when, in the summer of 2022, a European directive came into force requiring them to ask for information on their environmental preferences. The aim is to develop green investments and combat greenwashing by helping private individuals formulate concrete requirements.

The introduction of these rules has sparked panic among French banks, reluctant to see expressed expectations that they cannot meet. As reported by Le Monde , the banking lobby has exerted strong pressure on the Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF), the French supervisory body, in an attempt to weaken the new rules.

The French Banking Federation (FBF) expressed its indignation in an email to the AMF dated 1 June 2023, consulted by Le Monde : “Allowing customers to define preferences in terms of sustainability that have no relation to customers products available on the market can only lead to their misunderstanding". Translation: If customers can freely determine the percentage of “sustainable” companies in their investment portfolio, banking institutions risk having nothing satisfactory in stock to offer them.

“There is a tension between the idea of collecting fairly free preferences and the desire of retailers to orient consumers towards a range of products available to them,” underlines Philippe Sourlas, deputy director of the AMF.

A “benevolent attitude” on the part of AMF

When the answer is unpleasant, what's better than reformulating the question? This is what the FBF tried to do in a long exchange of letters with the financial supervisory authority on the interpretation of the directive, obtained by Le Monde thanks to the laws on the transparency of administrative documents. The lobby suggested letting bank advisors propose “realistic thresholds” for environmental requirements to clients.

The FBF did not want to answer our questions, but innocently says it welcomes "provisions that improve product transparency" for consumers. According to exchanges obtained by Le Monde , the AMF has refused to give in to the banks by revising its requirements downwards. On June 9, 2023, for example, the authority disputed some of their requests, underlining the “risk of misunderstanding on the part of the customer”.

However, in 2022, its president Robert Ophèle assured the FBF that his institution will “exercise discernment” in applying the regulations. In the name of a “benevolent attitude” in a context of multiplication of new regulations, Ophèle indicated that the control of these “new requirements” will not be a “priority”. To date, the Gendarme des Marchés Financiers has not issued any sanctions in this area.

Insufficient climate indicators

The reason why the topic of customer environmental preferences is so sensitive is that it highlights the contradictions of the banking sector. While marketing rhetoric increasingly places emphasis on the environment and investment funds presented as "green" have become the majority in Europe, the level of ambition of financial operators is often not up to par, as reports on the climate that the law recently required them to publish.

Some, like BlackRock, have not set themselves a climate alignment strategy. The world leader in wealth management believes that investments “should be made according to client instructions”.

Others play on their methodology to green their balance sheets. HSBC Asset Management, for example, only accounts for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the oil extraction process, without taking into account downstream fuel consumption, which accounts for the majority of emissions.

Some banks are more rigorous in this exercise, even if the results are not necessarily more reassuring. BNP Paribas Asset Management, for example, has calculated that 56% of the assets in its investment portfolios are held by companies "not aligned" with the Paris Agreement.

Amundi also calculates the "temperature" of its portfolios, i.e. the trajectory of global warming corresponding to its investments. The result: the trajectory is +2.8°C by the end of the century, far from the 1.5-2°C desired by the international community.

The defects of the ISR label

Several recent experiences confirm the shortcomings of "green" finance. In 2023, experts from the French Environment Agency (Ademe) have developed a methodology – still experimental – to evaluate the climate strategies of some financial institutions. The results, presented at COP 28 in December, speak clearly: not a single climate transition plan was deemed convincing.

One of the main pitfalls of current regulations is that they are essentially limited to transparency obligations. We must abandon the idea that publishing climate information is enough to redirect financial flows,” says Anatole Métais-Grollier, co-creator of the initiative together with Stanislas Ray of Ademe. It is the assessment of climate performance that is essential.

In France, the Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) label, created under the aegis of the Ministry of Economy, should help investors choose virtuous products. “If you are looking for funds that are climate positive, you can consult our list of funds with the SRI label,” explains a Boursora consultant as a sign of seriousness. Promise: “there will be no TotalEnergies”.

Wrong: SRI label specifications are much more permissive than you might think. According to a study by Epsor, a company specializing in employee savings plans, as of December 31, 2023, half of the funds that obtained the label invested in at least one company in the fossil fuel sector. The oil and gas giant TotalEnergies is even one of the most represented companies in these investments…". The annoying thing about the SRI label is that on the website you see wind turbines and bicycles everywhere, while that's not what you find in the funds at all,” complains Julien Niquet, president of Epsor.

Although this point was raised already in 2020 by the General Inspectorate of Finance, the rules for awarding the label were only tightened several years later. Starting March 1, 2024, funds applying for the label will no longer be able to invest in companies involved in fossil fuel expansion. Funds that have already obtained the SRI label, however, will have until 2025 to comply with the rule.

The setbacks of the SRI label and other attempts to establish a framework for green finance highlight the complexity of the issues at stake. “For financial flows to be redirected consistently, a truly common framework is needed to define which companies are environmentally virtuous and which are not. But this is a huge political burden that no one seems willing to take on,” observes Ademe's Stanislas Ray.

Despite the banking industry's reluctance, progress has been made in the fight against greenwashing in recent years. “There is a whole regulatory architecture being built in Europe that we hope will provide greater clarity,” says Julie Evain, financial regulation specialist at the Institut de l'économie pour le climat (I4CE). The fact remains that “financial operators are very good at making people believe that they are doing things. You have to read between the lines a little."

In his opinion, the fight against greenwashing cannot be limited to regulations: “We must also ensure that financial operators are aware of their responsibilities.

(Excerpt from the foreign press review edited by eprcomunicazione )

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/economia/tutti-i-bluff-della-finanza-verde-report-le-monde/ on Sat, 23 Mar 2024 06:13:52 +0000.