April 25 is Fyodor Dostoevsky’s conception of freedom

The Notepad of Michael the Great

For the second consecutive year tomorrow will be celebrated in a minor tone, without parades and rallies in the squares; and yet April 25 has never been the feast of all Italians. On the contrary, it was mostly experienced as a derby between opposing supporters: fascists against anti-fascists, right against left, bad against good. The truth is that, three quarters of a century after the insurrection that liberated the north of the country, we still do not have a shared memory, also because we have not yet fully come to terms with our past.

In 2019 the then Minister of the Interior Matteo Salvini preferred to spend it in Corleone to inaugurate a police station, arguing that the real liberation of Italy was that of the mafia. In 2020, however, a well-known FdI parliamentarian proposed turning it into a celebration of national harmony, in which to honor the victims of all wars. A singular idea, especially if we consider that national concord does not seem to be in the ropes of that party even at the time of the coronavirus.

Of quite another political-cultural significance, however, was to convert the Liberation Day into a Freedom Day, advanced in 2009 by Silvio Berlusconi in a speech given in Onna, a town symbol of the earthquake in Abruzzo. A serious and intellectually honest speech, in which the appeal to overcome a historic division did not diminish the reasons of the winners and the wrongs of the vanquished. Indeed, for the first time, the Knight unambiguously recognized the decisive contribution of the Resistance to the birth of republican democracy. Yet, it was submerged by a sea of controversy, and someone (the then governor of Puglia Nichi Vendola, not to mention names) flatly dismissed it as the profession of an "ugly revisionism, smelly and muddy".

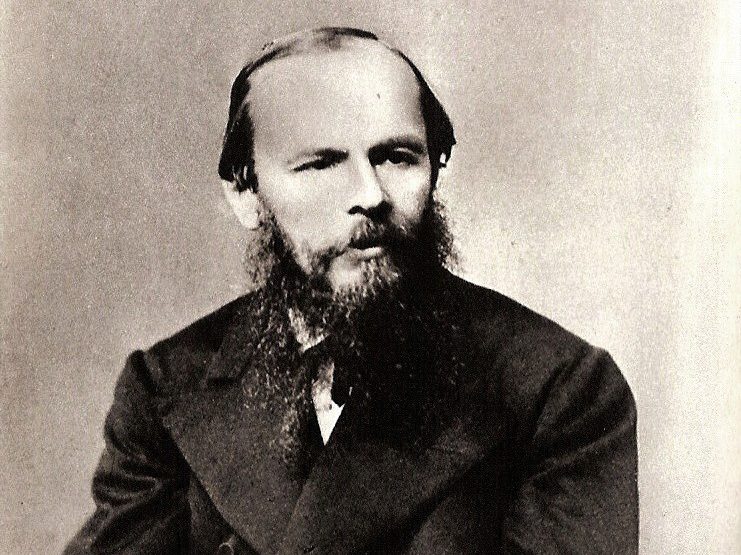

In my opinion, that speech would have deserved a more calm reception, and could be exploited to better reflect on a crucial question, namely whether Freedom (with a capital letter) can be considered a value, albeit the highest and most indispensable. Nobody is scandalized by it. I mean that, in reality, it is the condition for this or that freedom (with a lowercase) to be given. In this sense, he can decide for good as well as for evil, with sovereign indifference. It can even reverse itself in the act that denies or cancels it. In short, freedom – as Pascal's reader Dostoevsky well knew – comes before good and evil.

Be careful though. Because, as the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdjaev wrote, Dostoevsky himself “understood more deeply than anyone else that evil is the child of freedom. But he also understood that without freedom there is no good. Good too is a child of freedom. The mystery of life, the mystery of human destiny is connected to this. Freedom is irrational and therefore can create both good and evil. But to refuse freedom for the fact that it can produce evil means to produce an even greater evil ”( La Conzione di Dostoevskij , Einaudi, 2002). From this we deduce that, for the author of Crime and Punishment , freedom represents the foundations of the human building, and that its tenants are willing to suffer all the sufferings that the world can inflict in order to feel free. This is true not for everyone and not always, of course.

However, with April 25, 1945, was it not precisely the rebellion of a few that determined the freedom of all?

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/la-concezione-della-liberta-di-fedor-dostoevskij/ on Sat, 24 Apr 2021 05:30:31 +0000.