April 30, 1993, story of a lynching

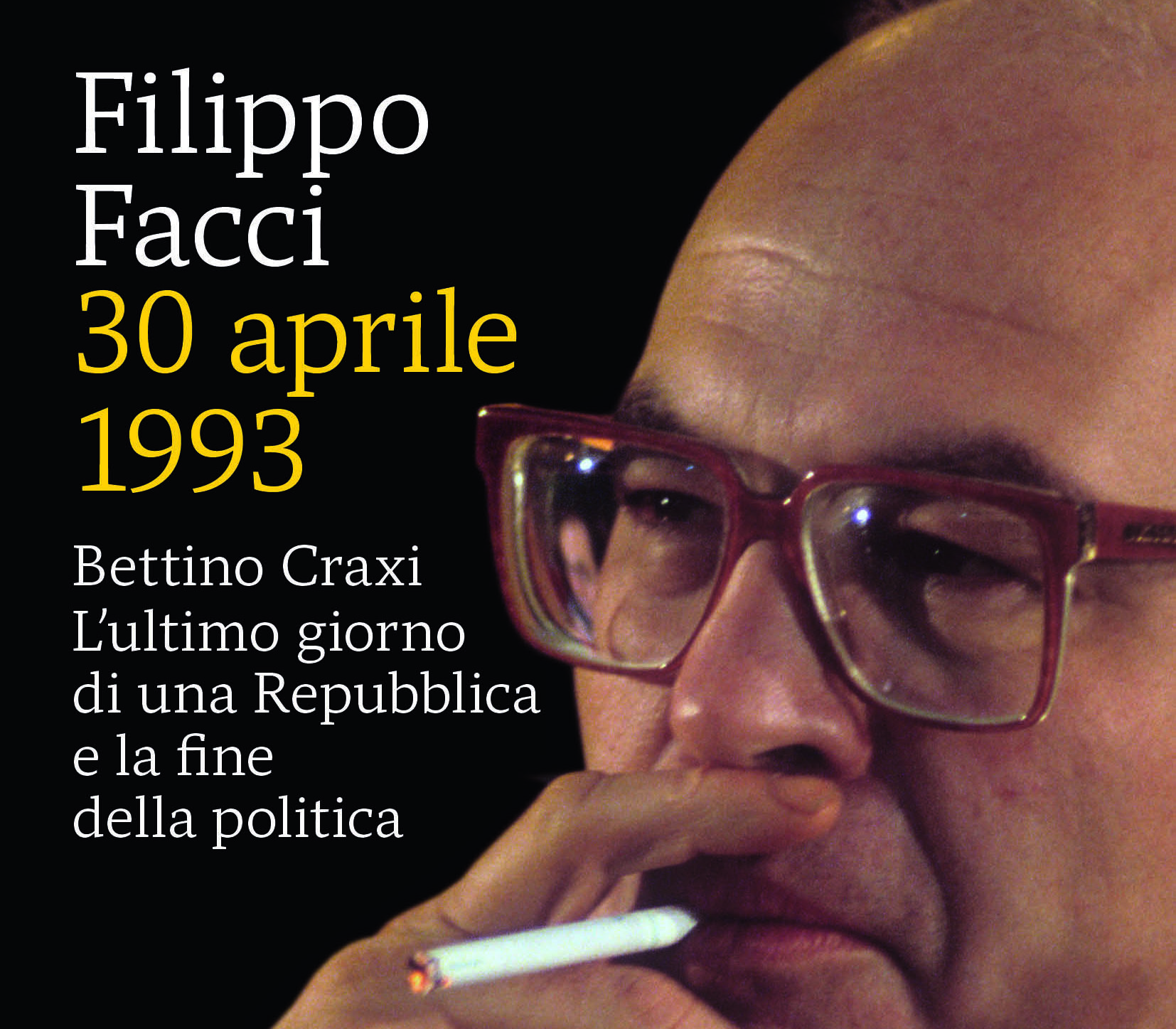

Facci's book "April 30, 1993 – Bettino Craxi, the last day of a Republic and the end of politics" (Marsilio publisher) yesterday was previewed by the Craxi Foundation. Paola Sacchi's point between news and history

Filippo Facci, as in a film, in frames, scenes that have remained unpublished until now, seen and experienced from the inside, not only from the outside, describes the "lynching", "violence, real violence" against Bettino Craxi, almost minute by minute.

Hotel Raphael, not just a toss of coins, an avalanche of coins, the tinkling of "metallic rain", but also of cobblestones, bricks, even an umbrella. The first "squadristic" aggression (words of Craxi who also defined them as "ruble takers") right up to his private residence which had never before been a political leader, former premier of the longest-serving government of the First Republic.

Facci's book "April 30, 1993 – Bettino Craxi, the last day of a Republic and the end of politics" (Marsilio editore), previewed yesterday by the Craxi Foundation with the publishing house, recalls Stefania Craxi, who founded the he historical institute, and today a senator of Forza Italia, "is the day in which the executioner monster was born". It is "the watershed date between the First Republic and today", says, introducing the works, the secretary general of the Craxi Foundation Nicola Carnovale.

"A bludgeon in the stomach, to re-read what happened in those 48 hours (after the Chamber denied many of the authorizations to proceed for Craxi, ed )", confesses Margherita Boniver, who was former minister at Raphael that day, and today president of the Craxi Foundation. Senator Stefania, now vice-president of the Foreign Affairs Commission of Palazzo Madama, does not give a testimony only as a daughter.

As Facci tells in the book, at the end of that April 30, at 11.50 pm, while she was in bed due to a complicated pregnancy, she was reached in Milan by a pained but dry and few words phone call from her father who told her: "A Craxi does not cry ”. Stefania emphasizes that hers is "a political battle". Because "Craxi fought in defense of the primacy of politics". Craxi, in fact, "did not defend an old and obsolete system, he asked for a political solution, but only part of the heirs of the PCI was preserved by Clean Hands", admonishes Stefania. He glosses: "Today Italy finds itself with all those unresolved issues, starting with the need for institutional reform, the one that my father launched with the Great Reform …". With very bitter irony the senator comments: "If Craxi was called the wild boar, Facci makes us feel the breath on the neck of the branches …".

Giuliano Ferrara, from whom Craxi, coming out that evening from the Raphael from the main door, refusing to take the secondary one, uselessly suggested to him by the escort for an entire afternoon, went on TV for the program "The investigation", stigmatizes "that disgusting Italy" of the "lynching". But the founder of the Foglio , who immediately denounced the serious precedent of the attack on a leader under the private residence, uses nuances that sound softer on today's Italy.

And instead, even for the former PCI Fabrizio Rondolino himself, "we went more towards the worst". Rondolino remembers that that evening he was right in front of Raphael a bit casually and since then the political notist of the Unit does not hesitate to say that he went away "frozen, with a changed idea about Clean Hands and also (here Rondolino breaks the taboo of a certain sacredness on Berlinguer, ed ) on the anti-socialism of the PCI secretary ”. He concludes: “Facci's book is beautiful and distressing, precious to remember”.

Fabio Martini, journalist of the Press , highlights what Facci denounces immediately in the book, which is one of the main reasons why he felt compelled to write it, namely that that attack in the newspapers of the next day practically did not exist, " drowned in a few lines of lead ". Just to Raphael some time before, Vittorio Feltri, director of Libero , the newspaper for which he writes today Facci, Feltri, the inventor of the term "the wild boar", tells of having changed his mind about Craxi: "He kindly received me in his apartment, it was not at all that palace that was described, it also seemed quite modest to me … ".

Craxi – with whom Facci in the book also remembers without rhetoric his personal friendship as a young twenty-year-old reporter, direct empathy, almost as if he were an ordinary man, with whom he immediately tuned in to the one who was instead a statesman – spent " the day he began to die ”with an apparent, cold calm. He only finally kicked the elevator as the crowd grew outside. And the police were finding it harder and harder to contain it. The leader and former socialist premier also apologized during the siege to the tourists who remained hostage with him inside the hotel.

Facci reminds us that most of the demonstrators came from Achille Occhetto's PDS demonstration, held in the adjacent Piazza Navona, and that there was also a minority close to the MSI. The Northern League was not there "because a procession was stopped earlier", according to the many testimonies collected. It reconstructs the dramatic moments in which the escort unnecessarily told Craxi not to go out the main door. And the leader of the PSI pretended not to hear. The same socialist entourage said to a policeman: “Enough. You tell Craxi to come out from the back ”. Out of the main door, the historic driver, Nicola Mansi, who remained with him at the end of the days of Hammamet , which would be an understatement to define only a driver, had a bloody head. Valeria Coiante, the journalist of Giovanni Minoli's “Mixer” shouted, under that assault, “they throw everything, they are pulling everything”. Let us remind you that only thanks to the TV, to that reporter, to a Mediaset operator and to a photographer who climbed on the roof of a restaurant, today we have the images of that April 30, which he felt the duty to remind the thirty and forty year olds of today. Not forgetting the chilling testimony of one of the "shooters": "We had to tear Craxi to pieces …". The beginning of "the false revolution, with fake heroes and fake revolutionaries". These are the words of Craxi, in a video, with which the presentation of “April 30th 1993” closed.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/30-aprile-1993-storia-di-un-linciaggio/ on Fri, 30 Apr 2021 07:56:25 +0000.