Are there no more clothes than they used to be?

The Notepad of Michael the Great

Why in the turn of the century, first in a silent form, then gradually more noisy and striking, did the distrust in parties explode so sensationally? At least in Italy, the answer that has perhaps received the most credit is also the simplest: the "caste" has become unbearable because the leaders have worsened. As they say, "there are no more the bosses they used to be". The elites are no longer, as Vilfredo Pareto wrote, elected classes made up of those who excel in various fields, including that of the art of governing (see Marco Revelli, “Finale di parte”, Einaudi, 2013).

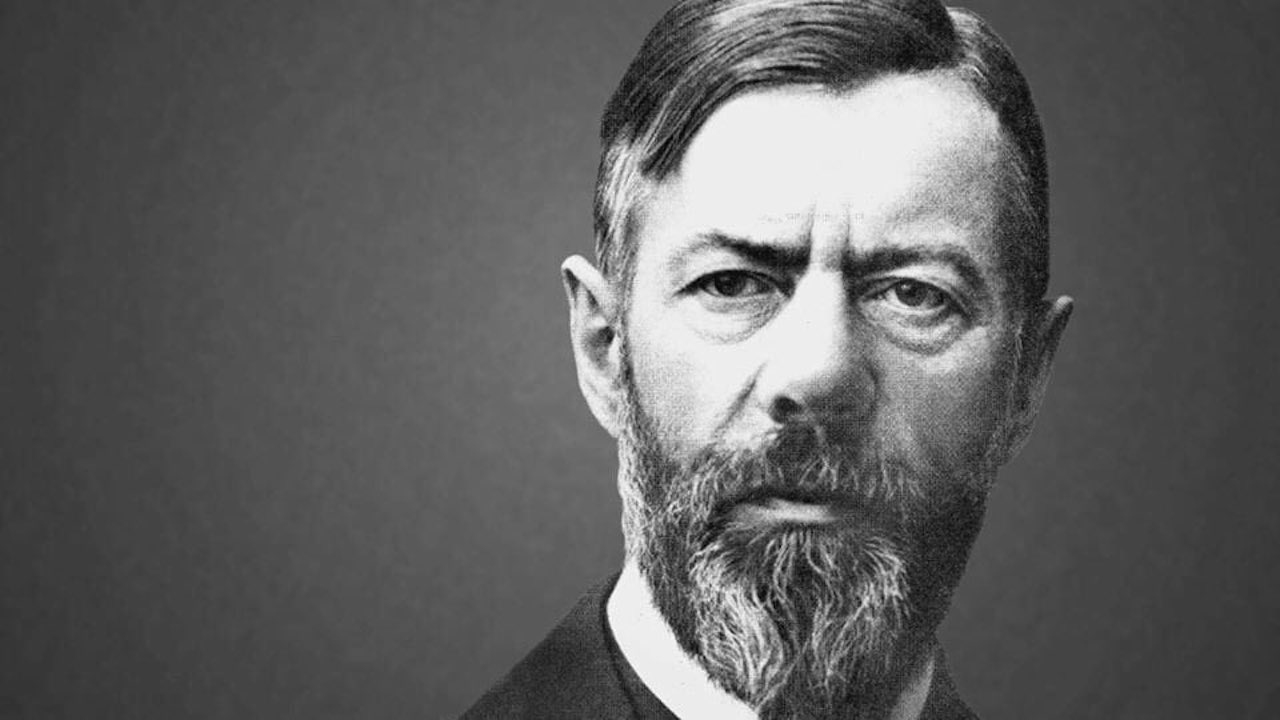

In Roberto Michels' analysis it was assumed that the garments were better than the crowd. Above all "in the parties of the proletariat – he wrote in 1911 – in terms of culture, the dukes are far superior to the army". As we read in the "Sociology of the political party" (il Mulino, 1966), "the gratitude of the masses to personalities who speak and write in their name, who have created a reputation as defenders and advisers of the people, […] is natural and often transcends the real tendency of the masses to venerate leaders ”.

None of this seems possible today. The current party leaderships are widely discredited, so much so that the only unanimous demand that arises "from below" whenever there is talk of electoral reform, is that of removing the power to decide candidacies from the party secretariats. The crowd of officials and middle managers who occupy the apparatuses, as well as the multitude of parliamentarians, are often considered as examples of unpreparedness, poor knowledge of problems, inefficiency and parasitism. They are also branded as venal and business, marked by the vice of privilege and a corporate spirit, as well as by widespread servility.

However, it would be necessary to understand why today the mechanisms of representative democracy, rather than the best, select the worst. There is an endless literature on this issue, which attributes to the system transformations – which took place in the final decades of the twentieth century – the reasons for the deterioration of political representation in democratic regimes. In one of his fundamental essays of 1974, "The decline of the public man" (Bruno Mondadori, 2006), Richard Sennet placed at the origin of the progressive erosion of public life, which we have witnessed for some time, a real cultural apocalypse, marked from the emergence of a hypertrophic and at the same time empty ego, which tends to project its narcissistic subjectivity onto the public space: feelings, emotions, drives, desires for success and visibility.

The same public space is thus invaded by the languages and narrative styles of a soap opera, in a continuous, banal and serial unveiling of oneself now free from any mystery or shame. This is what another acute investigator of the "culture of narcissism", Christopher Lasch, summarized in the essay "The culture of narcissism" (Bompiani, 2001) with the expression "rebellion of the elites", attributing to the dominant minorities the same vices and the same weaknesses that in 1930 another interpreter of the crisis of modernity, Ortega y Gasset, had attributed to those who should constitute their representatives (“La rebellione delle masse”, SE Editore, 2001).

****

According to Max Weber, the strength of the charisma lies in the divine ancestry which – be it kings or prophets – is usually associated with the leader, and in the messianic nature of his message. The charism is born from a state of grace, almost always combined with an openness to sacrifice as a palingenetic occasion. The charismatic leader by his nature promises a new beginning, and in this promise lies his ability to drag the crowds (see “The leader”, Castelvecchi , 2016).

When the great German sociologist was writing his theses, there was still no radio as an entertainment channel. The cinema was making its first silent steps. And television was not even imaginable. However, he had not underestimated the potential of charismatic power. With this brilliantly foreshadowing the irruption, after a few years across Europe, of visionary and magnetic leaders. Although they made extensive use of press propaganda and, from a certain moment on, of the radio, their appeal to the crowds was mediated above all by physical gatherings, by "oceanic gatherings".

What would have happened – a lucky TV ad about Gandhi will ask – if the charismatic leaders had had the modern means of communication at their disposal? Perhaps less than one might imagine. Because, as the new videoleaders would have learned the hard way, the media have the ability to make a new character and his message famous in a very short time; but, in equally rapid times, they can wear it down and destroy it. Of course, without taking anything away from the fact that television and social media have transformed the thousand real squares of a country into a single virtual square, with a practically unlimited capacity for communicative fire. Innovation that has also changed the nature of the message – and of the language – with which the new leaders address their audience (see Mauro Calise, "Offside. The left against its leaders", Laterza, 2013).

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/non-ci-sono-piu-i-capi-di-una-volta/ on Sat, 10 Jul 2021 05:27:50 +0000.