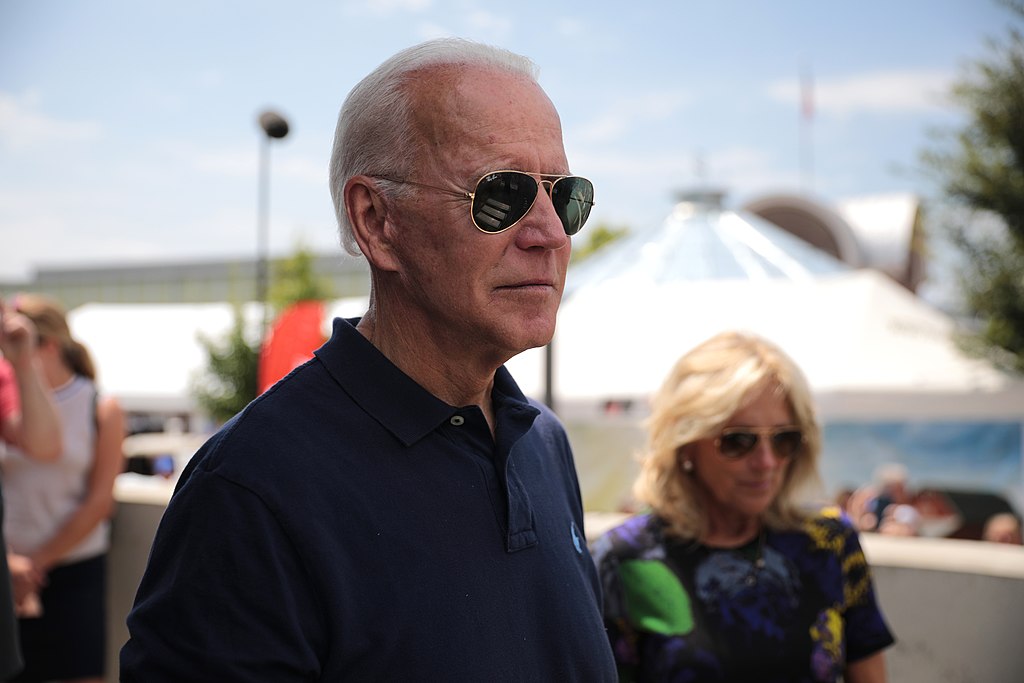

Because Biden wants more oil drilling. Economist Report

Biden has staked everything on the energy transition, yet right now his slogan is "drill". The Economist in-depth study

The global energy crisis caused by Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine has given Joe Biden's presidency a slogan usually associated with Republicans talking about energy independence: "drill, baby, drill". In addition to releasing 1 million barrels of oil a day from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the Department of the Interior will resume sales of new leases for oil and gas drilling on public land, reneging on Biden's campaign promise to end. to practice. Sounding a little less like a Republican, the president also suggested that long-term energy independence will only come from America's weaning off fossil fuels – writes The Economist .

Pump discomfort is most acute in California. On April 14, the average price of a gallon of gasoline in America was $ 4.07; in Los Angeles, full of freeways, it was $ 5.82 a gallon. Yet for all its gasoline consumption, California claims to be the greenest state in America. In a recent speech Gavin Newson, the Democratic governor of the state, proclaimed that "California is unmatched" in climate policy. Its annual budget proposal includes a $ 22.5 billion climate wish list that it would invest in electrifying transportation, strengthening public transportation infrastructure, and protecting people from droughts and fires. This follows decades of ambitious environmental policy that has influenced officials in other states, in the federal government, and abroad. How will the Golden State's green reputation hold up at a time of deep energy concerns?

Two policies stand out for their impact within the state and beyond. The first is California's unique ability among US states to set their own standards for vehicle emissions. In the 20th century, Los Angeles' growing population, topography, and expansion of the port contaminated its air. The sky was so dirty on a summer day in 1943 that Los Angeles residents feared they might be the victims of a war-related gas attack. Officials enacted limits on exhaust emissions in 1966 to try to tame the city's noxious smog.

Because California's rules preceded the 1967 Air Quality Act and the 1970 Clean Air Act, when federal officials first established national air quality standards, the feds granted the state waivers. which allowed it to establish its own stricter pollution rules. California has requested more than 100 waivers since 1967. Today, states can choose to adopt the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations for vehicle emissions, or those of California. By 2022, 16 states will follow California standards. The state's focused focus on car exhaust stems from two concerns: local air pollution and the global climate crisis. Transportation accounts for 29% of America's greenhouse gas emissions and fully 41% in California.

Los Angeles air quality is still often repulsive, but it has improved a lot over the past 40 years. Yet the Trump administration lifted California's waiver in 2019, arguing it shouldn't set standards for other states. The decision was the most serious manifestation of President Donald Trump's resentment of California's environmental leadership, says Richard Revesz of New York University. The EPA reinstated the waiver last month around the time it announced new federal pollution limits for buses, vans, and trucks based on similar rules in California.

The second reference policy dates back to 2006, when California passed a law requiring it to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. Britain was the first country to set a legally binding target for emissions, but only in 2008. Six months after the passage of the law Arnold Schwarzenegger, the governor of the time, was on the cover of Newsweek with a globe balanced on one finger. Mary Nichols, a former head of the California Air Resources Board (CARB), the state's air pollution regulator, recalls giving a lecture in Switzerland to crowds of people "who wanted to hear what California would do under Arnold Schwarzenegger. regarding climate change ".

The target was reached early in 2016. Lawmakers then called for the state to cut emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. Today California still has the second highest total emissions (after Texas ) among the 50 states. Yet in 2016 only New York had lower emissions per person.

California has been ahead of the cut in emissions for several reasons. First, it enjoys rare bipartisan support for bold climate action. CARB was created during Ronald Reagan's governorship in the 1960s. "Arnold Schwarzenegger was quite alone among Republican governors who deeply believe in tackling climate change," says Bill Ritter, a former Colorado governor who runs the Center for New Energy Economics at Colorado State University. States without climate-conscious democratic or conservative supermajorities cannot hope to move as fast. Voters are also on board. In a recent poll, 68% of Californians said the effects of climate change are already being felt, and nearly three-quarters said they support the 2030 target.

Second, California has the money and the manpower to invest in climate mitigation and adaptation. The Golden State is the fifth largest economy in the world. Thanks to a colossal budget surplus, Newsom's $ 22.5 billion climate project is nearly double President Joe Biden's 2023 budget request for the EPA. (Although the EPA is just one of many federal agencies that formulate climate policy). More than 1,700 people work for CARB.

Finally, Californians have been suffering from the effects of climate change for years. Fires have incinerated cities and their smoke has dirtied the air. The drought has dried up the water reserves. The extreme heat has baked cities and farms. And rising seas threaten coastal communities.

Few dispute California's past successes. But recently some have argued that his great successes – such as the implementation of a cap-and-trade system in 2013 – are long gone. State politicians are used to being criticized by their counterparts in Texas and Florida, but the harshest criticisms of the climate often come from within. “It is one thing to set goals, which we did very well,” says Anthony Rendon, the speaker at the California state assembly. "Another thing is to really reach them."

It could be heaven or hell

Skepticism about the state's ability to meet its climate goals may be justified. Last year a state auditor report said CARB failed to accurately measure the success of its electric vehicle incentive programs, leading it to overestimate emissions reductions. Data collection is only one of the problems. Some obstacles, such as the need to build transmission lines to import wind and solar energy from more inland states, are to be expected. But many obstacles have been created by California itself.

Consider Diablo Canyon, the state's only nuclear power plant, which is expected to be closed by 2025 despite being a clean and reliable source of energy. Diablo supplies California about 9% of its electricity production and accounts for 15% of its clean electricity production. California plans to replace the plant with other low-carbon sources, but can't afford to give up on basic power when it's trying to electrify everything from cars to stoves.

The Golden State's tireless NIMBYs are also hindering the fight against climate change. Anti-growth activists have used the California Environmental Quality Act to block public transportation projects and new housing, which are often denser and more energy efficient than old buildings and single-family homes. Estimates suggest California could produce 112 gigawatts of offshore wind power, but NIMBYs fear floating turbines will ruin California's coast.

Making matters even more complicated is the need to address short-term problems – such as high gasoline prices – while aiming to accelerate decarbonisation. The dispute in Sacramento over what to do about California's higher fuel prices embodies the state's contradictions on climate policy. Newsom's proposal to send $ 400 to all car owners has baffled some Democrats in the legislature, who argue that helping just motorists leaves out the poorest Californians who don't drive but are also crushed by inflation. Subsidizing gasoline also seems like a curious way to encourage motorists to buy an electric car or take the bus. The $ 750 million that Mr. Newsom would spend on subsidizing public transportation pales in comparison to the $ 9 billion he would spend on fuel discounts.

Californians in oil-rich Kern County are clamoring, like Mr. Biden, to drill, baby, drill. Most of the new fracturing permits were denied as California sought to phase out oil production. As fuel and electricity prices rise, lawmakers have to contend with ways to decarbonise without harming more and more residents and losing businesses in cheaper states. Republicans fear that the state's web of regulations, steep energy costs, and high taxes imposed in the name of greenery are hurting California's competitiveness. A 2021 report from Stanford University's Hoover Institution, a conservative think-tank, found that companies cited all three reasons they decided to leave the state, usually for Texas. In 2021, the cost of electricity in California was the third highest among the states, after Hawaii and Alaska. Part of this is because consumers pay the bill for utilities to upgrade their equipment to cause fewer fires. Rates are projected to continue to rise.

Years of climate denial under Trump and the current dysfunction in Congress mean states are leading the country's fight against climate change. California is one of four US states that helped found the Under2 Coalition, a group of subnational governments committed to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

But even if California and other green states can achieve their goals, a coalition of the willing can only do so much. The Rhodium Group, a consulting firm, estimates that 60% of emissions come from states with no climate targets. To force high emitters, such as Texas, to act, "joint action with the federal government is absolutely necessary," says Mr. Ritter. Last year Joe Manchin, the Democratic Senator from West Virginia, demolished his party's hopes of passing $ 555 billion in climate provisions that were part of the huge Build Back Better bill. democrats on a possible energy package).

While Congress stands idle, CARB has proposed banning the sale of new gasoline-powered cars by 2035. Biden's most modest national goal is for half of all cars sold in 2030 to be electric. . Regulators are also studying what it would take to decarbonise California by 2035, pushing the state's goals forward a decade. "I think sometimes there is an aversion to following California's lead because other parts of the country can have a strong reaction to the idea of being like California," says Aimee Barnes, a Jerry Brown climate advisor. former governor of the state. "And I think this is a mistake."

(Extract from the press review of eprcomunicazione)

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/energia/biden-petrolio/ on Mon, 25 Apr 2022 06:01:30 +0000.