Exorcism in the history of the Catholic Church

Michael the Great's Notepad

Forget the sensationalist stories about devil-possessed people you've read. The family massacre that occurred in the first ten days of February in Altavilla Milicia is just a story of macabre madness, of mystical deliriums, of improvised esoteric rituals, of torture with domestic utensils (a hairdryer, a pan, fireplace tongs), of disturbance of personality with criminal implications. However, the tragedy that took place on the outskirts of Palermo "during an exorcism", as numerous newspapers headlined, understandably alarmed public opinion and the community of believers. So much so that the International Association of Exorcists (IEA) immediately issued a note in which it expressed strong concern for the growing number of "unauthorised, false and scammers, who exploit people's pain and credulity, taking advantage of the religious ignorance and superficiality of which, unfortunately, many today are victims". Because "exorcism is carried out in the name and for the authority of the Catholic Church, by ministers appointed by the Catholic Church and according to the rites established by it".

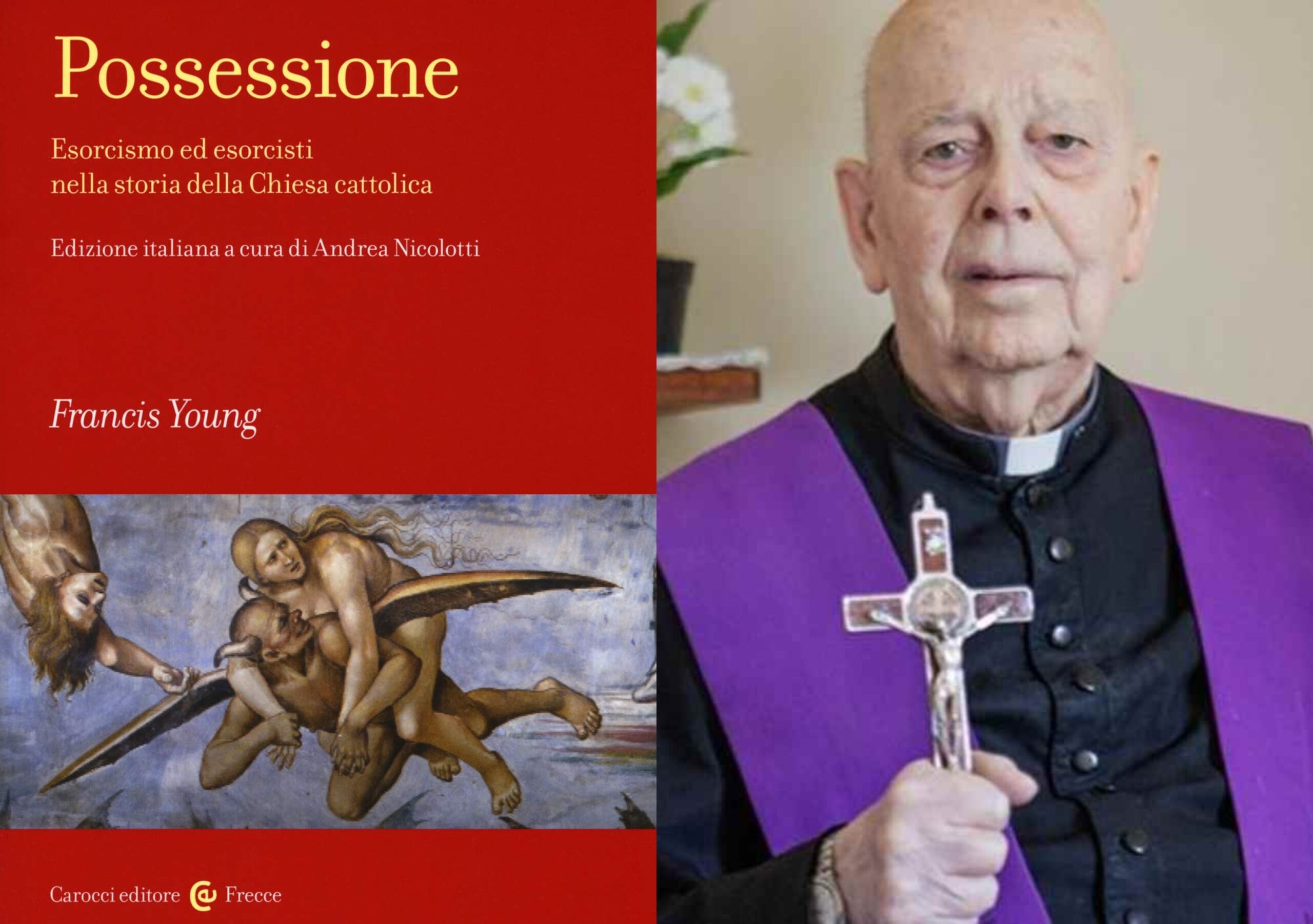

A copious popular literature has focused more on these rites, on the spells, the orders to the evil forces, the sprinklings with holy water, the contortions of the possessed, the vomited objects, than on the reasons for resorting to exorcism and its use as an instrument of power and propaganda. Francis Young is responsible for a masterly analysis of these reasons. The English historian observes that in its most flourishing periods exorcism is always characterized by the coexistence of two phenomena: divisions within the Church and fears towards an external enemy (the heretic, the sorcerer, the rationalist, the Freemason). The practice of exorcism, however, goes into crisis when one of the two is missing, or when more progressive theological currents prevail which seek to interact with science and the modern world (Possession. Exorcism and exorcists in the history of the Catholic Church, Carocci, 2018).

But let's go in order. We know first of all that the baptismal exorcism, established around 250, was a constitutive element of Christian initiation. True liturgical exorcism appears in the Carolingian sacramentaries of the eighth century, and throughout the Middle Ages it lives in competition with alternative methods of fighting demons, such as the charismatic power of the saints. In its current form exorcism was born in the sixteenth century and is the son of the Counter-Reformation. Previously it was aimed mainly against heretics and witches. Later, the “Rituale Romanum” (1614) regulates its rules and its exercise by priests. Finally, followed by the European rationalism of the Enlightenment and by the needs of social control of the popular classes, in the eighteenth century the practice of exorcism began a slow decline which ended in the following century, when it was bitterly opposed by the secular regimes in Spain and France.

“Spain and its territories – writes Young – represented the heart of the conservative tradition, while France was the center of a Catholic Enlightenment that expanded the boundaries of orthodoxy. Rome, trapped between the superstitious practices of overly enthusiastic exorcists and clerics ready to boldly deny the very reality of demonic possession, attempted to mediate, imposing increasingly severe supervision on the practice of exorcism: these controls, despite assurances that the doctrine did not had changed, produced the inevitable consequence of pushing exorcism to the margins of Catholic life." From 1740, in fact, the practice of exorcism clashed not only with the hostility of the ecclesiastical and civil authorities, but also with that of the medical professions, which denounced its fraudulent aspects. On 22 June 1744 Benedict When it comes to exorcising mobsters, it is essential to first discern whether the person who is claimed to be possessed by the devil really is."

The belief in a satanic and Masonic conspiracy to dominate the world led Leo XIII to compose the influential "exorcism against Satan and the apostate angels" codified for the first time in the "Ritual" in 1893. Exorcism thus returned to the fore in Twentieth century. Prominent exorcists such as Gabriele Amorth and José Antonio Fortea do not disdain the study of parapsychology and place emphasis on the dangers of satanic worship. In a general audience in November 1972, Paul VI reiterates the Church's teaching on the devil: “Evil [Satan] is no longer just a deficiency, but a living being. Terrible reality. Mysterious and scary." A dark metaphor, which cinema and the media have contributed to sedimenting in the collective imagination. Think of the success of the film "The Exorcist" by William Friedkin (1973), of the morbid curiosity aroused by the proliferation of satanic sects, of television programs dedicated to occultism, of editorial cases such as An Exorcist tells of Father Amorth (now in its twenty-first edition).

The presence of evil among men, of Satan with his army of demons, has occupied a very large space since the dawn of Christianity. The New Testament presents the Evil One as the great enemy God who prevents the advent of the messianic kingdom. All the biographies of the martyrs are interwoven with the incessant struggle with the devil, where temptation materializes in images, suggestions, disturbing or seductive, horrible or persuasive figures. The various hagiographic traditions and popular tales were not too subtle, and told of relationships with incubus devils: "For six years he abused her and tormented her with incredible lust" (Jacopo da Varazze, Legenda aurea, 1260-1298). We read about sexual relations between angels and women in Genesis, and in De civitate Dei Augustine (354-430), as Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) recalls, takes up an ancient myth which was still widespread in the Middle Ages: "Yes we hear repeatedly, and many confirm having experienced it, […] that the Sylvans and the Fauns, commonly called incubi, often dishonestly came forward to women, demanding and obtaining sexual union […]".

Another is the problem of demonic possessions, attested by the New Testament tradition and the lives of the saints. The devil who takes possession of a human body performs an entirely possible action. According to Bonaventura da Bagnoregio (1217/1221-1274), “Demons, due to their subtle and spiritual nature, can penetrate all bodies and remain in them without any obstacle, and can torture them unless they are prevented by a force superior” (Liber Sententiarum). Even Benedict of Nursia (480-547) had tested, at the beginning of his ascetic life, the temptations of the flesh from which he freed himself by throwing himself into a bush of thorns sharper than fire. On the other hand, Saint Francis (1181-1226), to free himself from "carnal heat", threw himself into the snow.

If the repugnant constitutes a constant sign in the apparitions of the devil, from the most ancient apocalyptic literature to the epic and chivalric poems up to the iconographic representations of modern times, another characteristic accompanies the devil as a symbol of the different: the color black, his "nigredo ”. The devil presents himself as “niger puer” to Anthony of Padua (1195-1231). Black as coals are the “unclean spiritus” that populate hell in the vision of the Irish knight Tnugdal (12th century). And it is always a "demon with the appearance of a very black Ethiopian" who torments the monk translator of the Koran Peter of Cluny (1092-1156). Another disturbing presence of demons is linked to the practices of magical arts, which are often combined with astrology. Sometimes, however, the devil is also capable of correct, almost exemplary behavior: in one of his sermons, Jacopo da Vitry (1165-1240) tells of a man who, to escape his "quarrelsome and adulterous" wife, decides to go on a pilgrimage in San Giacomo di Compostella. She asks him who he will leave in custody of her, and he angrily replies: “To hell with it!”. Immediately the devil shows up and prevents the wife's lovers from fornication. When her husband returned, she said goodbye with these words: "I would have preferred to look after ten wild mares rather than this terrible woman." And he leaves without asking for any reward.

At this point, let's try to sum up. Faith, the Bible, the Gospels, the lives of the saints, the Church attest to the existence of evil demons and make Christian spirituality a continuous "certamen" against them. This struggle responded to a crucial problem in religious experience: the active presence of adverse forces, of evil, of disorder. A difficult problem to explain in a universe which, as in the myth of Genesis, is formed by Yahweh, who on the sixth day rejoices in the goodness of his work: "And God beheld the things which he had made, and they were very good" ( 1.31). In the path of salvation that began with the temptation of Adam and Eve and the condemnation of Yahweh, the figure of Satan is therefore central. Throughout history the “civitas Dei” coexists with the “civitas diaboli' (Agostino, De Trinitate). In 1213 Pope Innocent III once again identified Muhammad as the Antichrist in his appeal for the crusade; shortly thereafter, the great clash between Frederick II and the papacy is also included in an apocalyptic scenario, as the extreme event of the struggle between the forces of good and the forces of evil, before the end of the world. Even the dramatic fall of Constantinople (1453) will be the work of the "precursor of the Antichrist, Sultan Mohammed II, "wicked and bitter persecutor of the Christian people" (E.Kantorowicz, Emperor Frederick II, Garzanti, 2017).

Later, Lucifer will infest Europe with "possessions", never as numerous as in the era of the scientific revolution and the birth of modern political thought, ranging from Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) to Hobbes's Leviathan (1651) . Furthermore, in the sixteenth century Satan was the author of the dramatic breakdown of Christian unity when he was identified, according to different polemical perspectives, as the Pope or Luther. The latter, who took refuge in Wartburg castle – where he translated the Bible into German – after his excommunication (1521), heard not mice, but legions of devils in the noises coming from the ceiling of his room. In this battle against the devil the Jesuits are at the forefront, and Ignatius of Loyola, in his Spiritual Exercises (1522-1535), meditated on the army of Satan theatrically arrayed against the army of Christ. And perhaps it is no coincidence that in the interviews and homilies of the Jesuit Jorge Mario Bergoglio the reference to the "prince of darkness", to the cunning serpent, is so frequent. As for Pope Montini, also for Pope Francis the devil is not a mythological figure, he is a real person, he is the "liar" who denies that Jesus is the Christ. However, a question could remain: if the fall of the angel and of man depends solely on the free will of the creature, and if the forgiveness of man was included in the merciful love of the Father, who predestined the redeeming Son Jesus, why does the concrete order chosen by God include that fall and therefore the reality of sin? This question is still difficult to answer: perhaps because it belongs to the "thought of the Lord", to his "unfathomable judgments" and his "inaccessible ways" (Paul, Letter to the Romans, 11, 32-34).

Let's go back to the present day. According to the Association of Catholic Psychologists, every year half a million Italians turn to an exorcist. The ecclesiastical instruction published in 1999 (“De exorcismis et supplicationibus quibusdam”) recommends that the exorcist consult with a psychiatrist “competent in spiritual realities” before starting the canonical rituals. Obviously the Poor Man of Assisi could not do it, but he taught an extraordinarily effective exorcism to Brother Ruffino. The friar was assiduously tempted by the devil who, in the guise of Christ, urged him to leave the ascetic life. Since prayers and fasting were not needed, Francis advised him on what he should say to the devil if he came back to tempt him. Ruffino, obediently, followed his instructions. Here is the devil who says to him: "What does it profit you to grieve while you are alive, and then when you die you will be damned?". And Brother Ruffino immediately responds with the words suggested by the Poverello of Assisi: “Open your mouth; I'm shitting you now." At which the devil, indignant, immediately departed with such a storm and commotion of stones from Mount Subasio which was high up, that for a long space the ruin of the stones falling down was enough" (I Fioretti di san Francesco, edited by B. Bughetti, Città Nuova, 1999).

* The paper

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/esorcismo-nella-storia-della-chiesa-cattolica/ on Sat, 02 Mar 2024 06:07:55 +0000.