I’ll explain the effects of the demographic winter on the labor market

It didn't take much to understand that Italy was on its way to a demographic winter: that's why. Giuliano Cazzola's analysis

Among the great emergencies of the country there is one that for some years has conquered its "place in the sun", in the sense that it has become evident, so much so that it raises concerns not only among those working in the sector (in our case the demographers , statisticians and actuaries), induces governments to take measures, but which is unsolvable (assuming and not granted that the situation is not already compromised) if not within the space of several decades and many generations.

This emergency has been given a name, like the typhoons that periodically devastate the Gulf of Mexico (and its surroundings): it is called demographic winter, and it indicates an inexorable decline in the population residing in the Bel Paese, caught in the grip of aging and of the falling birth rate.

As regards this last aspect, in the span of a generation we have gone from the historic peak of 1.1 million births in 1964 to 398 thousand in 2021 (a figure which in the past was the consequence of tragic events such as a war or a 'epidemic). Obviously these processes are not determined by a sudden collapse but by a long haemorrhage which gets worse year after year, due to a progressive decline: when the generations (net of other cultural, economic and social factors) decrease in number, they trigger a supply chain that will produce a further decline in the subsequent ones.

The presence of a decreasing number of fathers and mothers (of childbearing age) brings with it the inevitable consequence of a reduction in the number of children, in a sequence that is dragged downwards as the cohorts succeed one another. Demography is almost an exact science because it reasons on certain data, because it has already taken place (births) and on generally predictable variables (except in exceptional cases). It didn't take much to understand that Italy was on the path to decline. Even politics was aware of this. I remember that at the beginning of the 1990s, in my role as a trade unionist, I happened to meet Carlo Donat Cattin, then Minister of Labour, on the question of pensions during a legislature in which all the holders of that Dicastery had ventured (unnecessarily ) with attempts at reform that not only did not succeed but also failed to enter and leave the Council of Ministers. Donat Cattin put the demographic question on the table by evoking gloomy scenarios in the not too distant future. But he too was induced by politics to allocate huge resources to the treatments in force, under the pretext of the so-called annual pensions, or by putting an ex post remedy to regulatory changes which had penalized pensions over time.

The reforms of the system began in 1992 by the Amato government; then they continued including structural reorganizations and steps backwards, but almost always safeguarding the generations close to retirement to the detriment of future ones. Basically, the baby boom cohorts were able to put in synergy with rules that (albeit with modifications) favored early retirement without penalties with favorable demographic trends, long periods of early, stable and continuous employment, lengthening of life expectancy in reason of one year every ten.

And herein lies the bottleneck that the trade unions refuse to see: in the next few years the number of pensioners classifiable as old/young will increase while the number of taxpayers in a pay-as-you-go financing system will decrease – because they were not born to an adequate extent. All this net of many other reasons such as the employment and economic conditions of the generations who will enter the job market.

It would not take much to understand what consequences the interweaving of these processes will bring about: falling birth rate, ageing, increase in life expectancy and the prevalence of early retirement which is safeguarded – albeit in a messy and contradictory way – also by the first budget law of Meloni government.

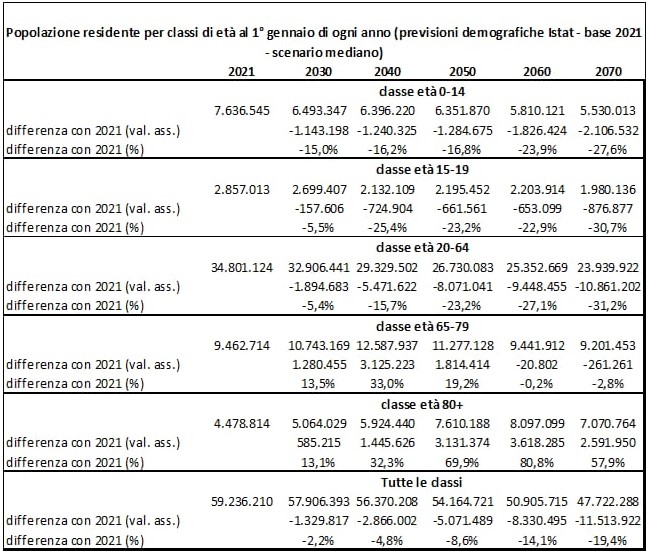

The table that is published below helps to understand at a glance what effects are expected on the labor market side. In the central cohorts between 20 and 65 years of age, at the end of the decade 1.8 million people will be missing, who ten years later, in 2040, will become 5.7 million, who cannot be replaced by the following cohorts, also in a decreasing trend. It should be noted that this is a resident population: which means that flows of foreign workers are also included. However, since 2014 the contribution of immigrants is no longer able to compensate for the negative balance of Italians.

It is also appropriate to note the typification of the demographic decline. In 2040 – a near goal – the resident population will decrease by 4.8% compared to 2021. If we go further, the data is sensational. The ''gap'' is located precisely in those cohorts which are central to the labor market. More generally, it is not reassuring to observe that in 2050 the very young (from 0 to 14 years) will be overtaken even by the over 80s. Already in 2040 the residents who – according to the current rules and those that many alleged reformers have in mind – will be in retirement or pensions (aged 65 and over) will amount to more than 18 million, to which must be added the 6 million of the under 14s. Not bad for a combined population of 56 million.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/economia/inverno-demografico-mercato-lavoro/ on Wed, 28 Dec 2022 06:17:05 +0000.