Is the US bank Charles Schwab creaking?

After a month of the Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse cases, the symptoms of a potential banking crisis starting from the USA have not subsided, as can be seen from the numbers of Charles Schwab. Here because. The analysis by Stefano Feltri, former director of the newspaper Domani and editor of the Appunti newsletter

Just a month has passed since the sudden crisis of the Silicon Valley Bank , the bank of reference for technology companies, which went bankrupt in a weekend due to the sudden exit of deposits due to a crisis of trust among account holders and the consequences of the increase in interest rates of interest.

The American authorities then guaranteed all the deposits, even above the threshold of 250,000 dollars, and in Europe the regulator and the Swiss central bank organized the rescue of Credit Suisse by UBS, the epilogue of another crisis of confidence not directly connected to the sooner but at least as dangerous . And now, is it all over?

Serenity seemed to have returned to the stock market, in the last month the Stoxx Europe 600 banking index even gained 6.53 percent . And yet it's not over. Just not at all.

WHAT HAPPENS TO CHARLES SCHWAB?

Now the focus is on Charles Schwab , a bank with a balance sheet nearly three times that of Silicon Valley Bank, with assets of $552 billion.

Unlike Svb, Charles Schwab is a bank specializing in retail services, i.e. to ordinary customers, rather than start-ups and investment funds.

Deposits at Charles Schwab are down 30 percent from a year ago, and 11 percent year-to-date.

This is not a good sign: the flight of deposits can cause a bank to fail. As was the case for Svb and in the age of smartphones, there is no longer even a need for a physical “bank run” to trigger the collapse, just a few clicks on your bank's app to move the money elsewhere.

Banks are structurally exposed to the constant risk of bankruptcy, their entire business model is based on the assumption that depositors do not all go together to ask for the money back that they have short-term loaned to the bank.

Even if we never think about it, the money in our current account isn't all really there: we lent it to the bank which then uses it as it sees fit (and as the rules permit).

In practice, it is financed at almost zero cost by us depositors, indeed usually it also charges us commissions for the management of the current account, but then it lends that money in the long term at higher rates, for example for business loans or real estate mortgages for families.

If depositors start asking for their money back, the bank is simply not in a position to please them all.

The guarantee of the Fdic fund (in the US, Fitd in Italy) should discourage the "bank run", in the sense that it should defuse the motive to rush to withdraw the money before the bank fails and is unable to repay it.

But it cannot prevent depositors from calculating and understanding that it is much more rational to move the money elsewhere because, simply, it yields more than in the current account.

An issue that did not arise when interest rates were around zero or below zero, but now that safe government bonds yield around 5 per cent, and that inflation is eroding the sums still in the account, the more rational savers move their money elsewhere. And even the banks themselves, as Charles Schwab's balance sheet shows.

AFTER SVB, CHARLES SCHWAB?

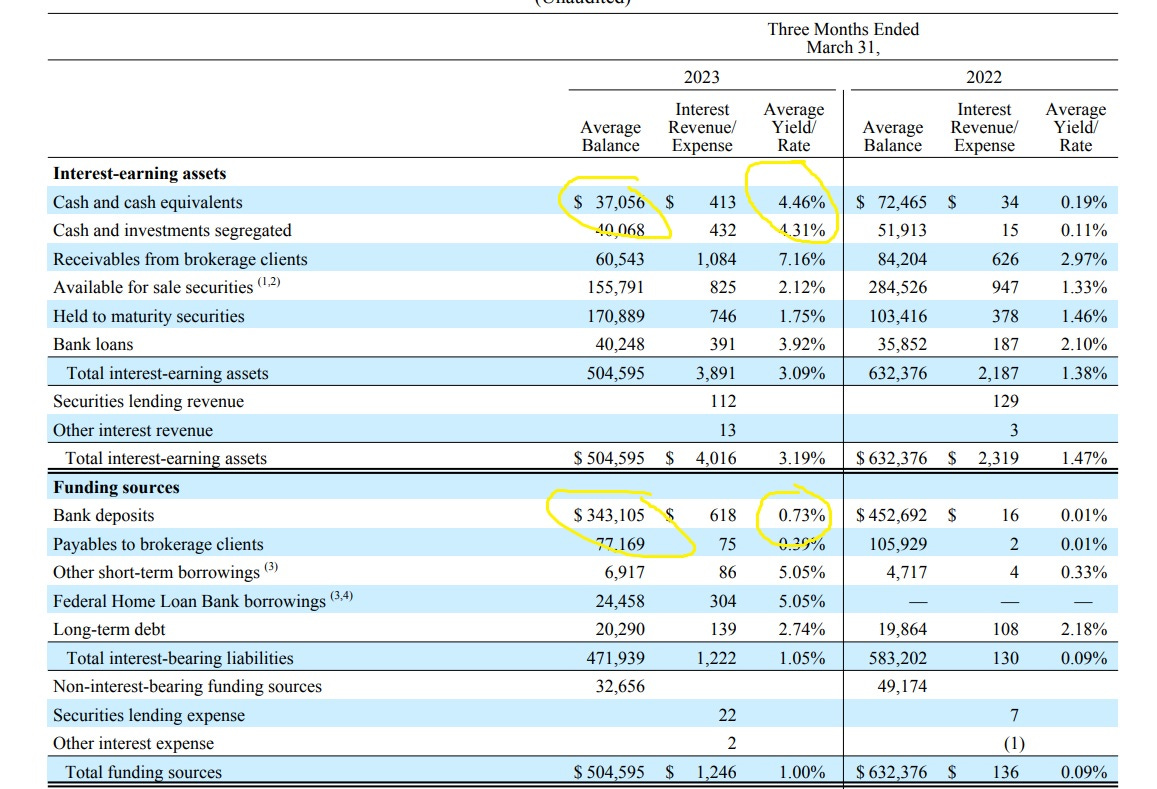

Deposits at Charles Schwab fell from an average $452.7 billion in 2022 to $343.1 billion in Q1 2023. This form of financing costs the bank just 0.73 percent in remuneration to depositors, which is to say depositors collect almost nothing.

Very liquid and short-term securities, so safe and marketable that they are classified together with cash (under the heading "cash and cash equivalents") yield Charles Schwab 4.46 percent while in 2022 they averaged 0.19 percent , before the Federal Reserve started raising rates

Charles Schwab's smartest customers are therefore shifting their savings from current accounts to safe and profitable forms of short-term investment, as demonstrated by the fact that the money market funds managed by the same bank have almost doubled the sums invested, from 144.7 billion in 2022 to 316.4 in 2023.

In short, with these numbers, banking crises seem not only inevitable, but even rational. Why should savers give away the returns guaranteed by interest rate increases only to the banks, while also bearing the costs of inflation?

Like banks, insurance systems are also based on the fact that not everyone is compensated at the same time.

The Fdic, the fund which should now guarantee all American deposits up to 250,000 dollars, has an endowment of around 128 billion , just right for a medium-sized banking crisis. Certainly not to really repay millions of account holders in the event of a systemic crisis.

INSOLVENT

One ingredient is missing from this potential slow-motion catastrophe: the effect of rising interest rates on the value of bonds on the balance sheet. Both SVB and Silvergate, the other bank that went into liquidation before the bank run, had invested the bulk of their assets in securities with maturities of at least 10 years ( 79 per cent of SVB's assets and 73 per cent percent of Signature ).

Customers can get their money back with one click, banks take a decade: the balance is fragile and relies, in fact, on customers' willingness to let inflation erode their savings while banks make money on the difference between the low rates paid to depositors and the high rates collected on loans or investments.

However, if interest rates rise as a reaction to inflation, the value of those long-term securities falls: nothing wrong if the bank keeps them on the balance sheet and simply collects the coupons waiting for repayment, but has to sell them to repay the depositors who claim their savings back, then the capital loss materializes and the bank risks collapsing (as happened to Svb).

So how many US banks are potentially insolvent? Probably all, answer the economist Lawrence Kotlikoff and the investor Rick Miller , in an article on ProMarket.org, if the bonds on the balance sheet were valued at market values.

(Excerpt from an article published in the Appunti newsletter by Stefano Feltri, former director of the newspaper Doman i)

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/economia/la-banca-americana-charles-schwab-scricchiola/ on Tue, 18 Apr 2023 06:36:06 +0000.