Italian intellectuals and the myth of Vietnam

The Notepad of Michael the Great

By the mid-1960s, the Viet Cong liberation struggle had already become a myth. Neither the guerrillas then active in Asia and Latin America, nor the Algerian or Palestinian resistance won such broad international support. In Italy, the communists and the exponents of a magmatic and minority neo-Marxist intellectual environment contributed above all to the birth of that myth. As Francesco Montessoro wrote in a golden writing to which these notes are indebted, however, Catholic and liberal socialist circles also played a not inconsiderable role, close to the positions of liberal Americans, Protestant churches, European social democrats, variegated Third World nationalism ("The wars of Vietnam ", Giunti).

To a large extent, that myth was based on the political and military choices of Ho Chi Minh and General Giáp aimed at defending the independence and unity of the country, crushed by the authoritarian regime of Saigon and by American prevarication. On the international level, the idea of their full legitimacy was rapidly affirmed, as they sought to remedy a vulnerability dating back to the non-application of the Geneva agreements of 1954. Hanoi was thus able to obtain substantial political, military and economic support from China and Soviet Union; and it was a question of support that was by no means taken for granted, also due to the disagreement that then opposed Moscow to Beijing.

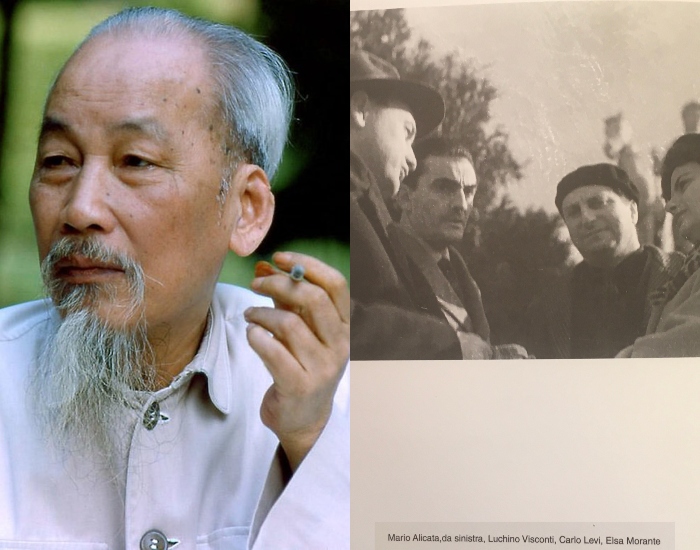

With the other America for peace in Vietnam! ”: With this title the PCI daily“ l'Unità ”announced, on November 27, 1965, the beginning of a vast popular mobilization against the American invasion. The choice of date was not accidental. On the same day, in fact, protest marches were planned in numerous European countries and an impressive march of American pacifists in Washington. Its promoters included Albert Sabin, Saul Bellow, Arthur Miller and black leader James Farmer. In Rome, a famous vigil at the Adriano theater attracted the support of politicians of different orientations, trade union, cultural and religious organizations. Dozens of intellectuals and artists responded to the appeal of the promoting committee (first signatories Eduardo De Filippo and Luchino Visconti), including Norberto Bobbio, Giacomo De Benedetti, Walter Binni, Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the New York Times published shortly thereafter the famous "Call of the Forty-Six", signed by European artists and intellectuals. Alongside those of Jean-Paul Sartre, Heinrich Böll, Simone de Beauvoir, Margherite Duras, Max Ernst, and then of Günter Grass, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Karlheinz Stockhausen, there were also the signatures of eight Italians: the filmmakers Michelangelo Antonioni, Cesare Zavattini, Francesco Rosi, the sculptor Giacomo Manzù, the writers Alberto Moravia, Ignazio Silone, Lorenza Mazzetti and a democratic, cosmopolitan and heretic anti-communist like Nicola Chiaromonte.

Beyond the fascination exerted by the resistance of the Vietnamese people, in many of them there was a prevailing interest in the areas of the Third World where revolutionary processes were underway: Cuba and Latin America, Algeria, China and , in fact, Vietnam. Moravia, in 1967, wrote on the Chinese cultural revolution benevolent cursives, and at the XXVIII Venice Film Festival, in the same year, films with evocative titles such as "The Chinese" by Jean-Luc Godard and "China is nearby" by Marco competed. Looker. At that time Renato Guttuso and Italo Calvino were also very active, who in September 1966 had agreed to write a short text against the Vietnam War for a British publisher.

Calvino, who had left the PCI in 1957, stated in that text that "in a world where no one can be satisfied with himself or at peace with his conscience, in which no country or institution can claim to embody a universal idea and not even just their own particular truth, the presence of the people of Vietnam is the only one that throws a ray of light ”. In a united Vietnam "under the rain of bombs and napalm", he continued, there were three exemplary images: "the righteous and patient men of Hanoi who rule a country victim of excessive and abominable violence"; the guerrillas of the countryside of southern Vietnam, “which of all the partisan struggles of our century is the most widespread and the most supported by the inhabitants, the most ingenious”; the Buddhist monks, "who in order to shout the word peace louder than the noises of war" make "the flames of their own bodies sprinkled with petrol" speak.

Giovanni Arpino, Riccardo Bacchelli, Giuseppe Berto and Mario Luzi also responded to the request of the curators of “Authors take sides on Vietnam”. Arpino admitted that he did not know what to suggest to end the war. Bacchelli refused to give any appreciable opinion. Berto classified the Vietnam issue among the gossip and wasted time of the Italian political class. Mario Luzi, on the other hand, denounced the American intervention in Vietnam as an example of the old power politics. In 1966, the musician Luigi Nono dedicated the notes of “A floresta è jovem e chea de vida” to the National Liberation Front of Vietnam. Subsequently, in April 1967, while participating in a famous meeting at the University of Rome, he expressed decidedly radical opinions, which he specified in an intervention published by the PCI weekly "Rinascita" "[…] Vietnam is also in our house, in Italy as in France […]. Vietnam in Europe is also and above all in the factory an essential component of society, in which capitalism exercises the maximum of oppression and exploitation ”.

In May 1967 "Rinascita" also hosted an article by Marcello Cini, professor of theoretical physics at Sapienza. A member of the PCI, but later one of the founders of the magazine and then of the newspaper "Il Manifesto", he was part of the Russell Tribunal delegation sent to North Vietnam to document the devastation caused by American bombing. In reality, his accounts did not describe so much the struggle to reconstruct the unity of a nation divided by the logic of opposing blocs, as the original character of the socialist society that Ho Chi Min was building. Sensitive to Maoist suggestions, he concluded that "on the part of the workers' movement of the western capitalist countries […] support for Vietnam must go beyond the dutiful protest against injustice and generous solidarity with an attacked country, but it must become aware of the close interdependence that binds all the struggles for socialism in the world ”.

Even in secular and progressive circles that were not prejudiced against the American background, the anti-colonial demands that were germinating in the countries of the Third World were welcomed with sympathy. In the early 1960s, the first articles on Vietnam appeared in periodicals such as “Il Ponte” or “Comunità”. “Comunità”, the magazine commissioned by Adriano Olivetti, hosted one of the first contributions on the Vietnamese question in the spring of 1963, and it was significantly an appeal by intellectuals and personalities from overseas in favor of peace. A culturally similar role to “Community” was played by Il Ponte, a monthly linked to what had been the Florentine Action Party, and around which famous figures such as Piero Calamandrei, Tristano Codignola, Giorgio Spini gravitated. Under the direction of Enzo Enriques Agnoletti, the monthly stood out for the first-hand information it provided on the international campaigns that were being organized in those years to challenge the policy of Lyndon Johnson's administration.

The names of Danilo Dolci and Aldo Capitini also stood out in this cultural milieu. The first, clear figure of a pacifist linked to Capitini himself, committed against the mafia in Sicily, became a member of the Russell Tribunal in 1966 and the following year organized a peace march in Vietnam that crossed Italy, urging the Moro government to distance yourself from the American invasion. Even more clear are the positions of Aldo Capitini, the organizer in 1961 of the first "march of peace Perugia-Assisi".

Anti-fascist and democrat, pacifist and non-violent, animated by a profound and free religious spirit, Capitini wrote in 1964 some articles on the Vietnam War in which he praised the deeds of the Vietnamese Buddhists, for whom "suicide becomes the ultimate attempt to protest choosing between the death of the other and one's own – as if death ultimately takes us to change the situation – one's own death ”. The recognition of such a value to the extreme manifestations of the protest of the bonzes led him to indicate neutralism as the only and desirable possible political perspective: "Not only in Viet-Nam, but also elsewhere is this orientation: building neutrality […], and if neutrality is broken, rebuild on the unifying basis of the nonviolent method. In order to oppose communism and establish strategic positions, the Americans believed they would find the right man in Diem […]. It is not excluded that after the bankruptcy the United States will pass to an even more visibly imperial dominion. Praise be to the Buddhists for having faced the oppressor ”.

The Vietnamese question appeared relatively late in the literature of the radical left, especially in that which aimed to free itself from the hegemony of the PCI. Only in the first months of 1964 was it dealt with in the columns of the quarterly “Quaderni Piacentini”, translating some letters from South Vietnamese partisans. On the other hand, a talented Sinologist, Edoarda Masi, in 1965 had published in the "Quaderni Rossi", the Turin periodical founded by Raniero Panzieri, "Revolution in Vietnam and the Western labor movement". An essay, published by Einaudi in 1968, which would have profoundly influenced the debate on the meaning of the Vietnamese revolution. Masi interpreted it as an unequivocal sign of the crisis of the capitalist system, which required a new strategy of the international workers' movement.

At the end of 1967, "Quaderni Piacentini" published a document drawn up by the editorial staff of Quaderni Rossi, "Vietnam and the international situation", intended for discussion in the student movement. The Vietnam theory was returning as a "test bed" of possible revolutionary experiences in the West. Even the bimonthly "Quindici", linked to exponents of the literary avant-garde such as Alfredo Giuliani, Edoardo Sanguineti, Angelo Guglielmi and then, among others, as Nanni Balestrini, Alberto Arbasino, Umberto Eco, considered the Vietnamese question as crucial to understanding that rebellion youth who, on both sides of the Atlantic, raised the portraits of Che Guevara, Mao and Fidel Castro.

In Italy, at the time of the pontificates of John XXIII and Paul VI, the request for renewal of the Catholic world arising from the Second Vatican Council had opened a discussion on the commitment of the believer in society. In this context of cautious dialogue with Marxist culture, the Vietnamese conflict became a sort of watershed between the pro-American positions of the leadership of the DC and the exponents of "dissent" led by Giorgio La Pira. Trained at the school of Emmanuel Mounier, Jacques Maritain and Luigi Sturzo, deployed on the Dossetti left, the former mayor of Florence played a notable role in the pacifist movements that fought against the danger of nuclear war. In 1959 he went to Moscow, in 1964 to the United States and, the following year, he met Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi. On his return to Italy, he was the bearer of a message from the president of North Vietnam which was delivered, through Foreign Minister Amintore Fanfani, to Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

The same ecclesiastical hierarchies and Vatican diplomacy did not fail to pay close attention to the development of the revolutionary tensions that swept through Asia and Latin America. In the encyclical "Christi Matri" (September 1966), Pope Paul VI exhorted all the belligerent parts of Vietnam to "fair negotiations". An invitation aimed at blunting the extremist and traditionally pro-American attitudes of Vietnamese Catholics, who in the 1950s had expressed a very questionable personality such as Ngo Dinh Diem, supported by Cardinal Spellman and guarantor of an inflexible anti-Communist crusade.

In a subsequent encyclical, the "Populorum Progressio" (March 1967), Pope Montini will emphasize the renewal anxieties of a part of the Catholic world, but without justifying armed rebellions: "The temptation to let oneself be dangerously carried away becomes more violent. towards messianisms full of promises, but makers of illusions. Who does not see the dangers that derive from it, of violent popular reactions, of insurrectional agitations, and of slips towards totalitarian ideologies? ”. But it was a tempered condemnation, so to speak, from these words: "We know that the revolutionary insurrection – except in the case of an evident and prolonged tyranny that seriously undermines the fundamental rights of the person and dangerously harms the common good of the country – is a source of new injustices, introduces new imbalances, and causes new ruins ”.

Of another opinion was "Testimonials". Expression of radical Catholic circles, linked to the experience of the Isolotto community, the Florentine monthly became the seat of heated debates on various ecclesial, ethical and political issues, including that of the legitimacy of violence for "just reasons". The Vietnam War began to be cited in its columns with greater frequency starting from 1966. The Vietnamese question, in particular, was dealt with in a reflection on Father Ernesto Balducci's "Populorum Progressio": "The Church cannot fail to recognize a total equality of civil and ecclesial rights for all peoples and all races, but, by virtue of its actual situation, it cannot fully recognize those rights, for fear of losing the human guarantees of its very survival ”. Balducci then urged the Church to carry out courageous gestures: "How can we become heralds of peace and meekness to the Negroes, the Vietcong, the guerrillas from all over the world, we who in the past have justified wars waged for a just cause?" . And he concluded: “Thus we find ourselves, for having sinned against the absolute imperatives of the faith, to appear in solidarity with the rich and oppressive peoples, and not to have sufficient moral prestige […]. I find the sign of so much anguish in me, a convinced supporter of non-violence, when, faced with some extreme situations of these times, I find myself wondering if violence is not the only way imposed by love ".

Far more prudent were the positions of Catholic civilization . The organ of the Italian Jesuits did not skimp on precise information on the Vietnamese question, without, however, any particular emphasis. The articles, always anonymous but probably written by the Jesuit Giovanni Rulli, were included in the “Abroad” section of the “Contemporary Chronicle” column: a low profile position. In these articles, of moderate inspiration and substantially pro-American, the author usually emphasized the strategic value of Washington's humanitarian aid to the Saigon regime, to the point of considering it a necessary tool to pave the way for a negotiation. A thesis destined to be blatantly denied by the progressive resurgence of the conflict, which ended on April 30, 1975 with the fall of Saigon.

Historical similes are always arbitrary, but there is no doubt that, despite all its ambiguities, illusions, ideological ambitions, the Italian progressive intellectuality during that conflict did not hesitate to "get its hands dirty". Thinking about today, that is, his commitment against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the confrontation is merciless. Four of the nine books of the famous "Stories" of Herodotus are dedicated, according to the division of Alexandrian grammarians, to those "Persian wars" which for about twenty years (499-479 BC) saw the Greek polis engaged against the empire founded by Cyrus the great. As they have been interpreted and handed down by the historian of Halicarnassus, they were wars of freedom waged by a small people against a powerful adversary; and that precisely because he fought for a great cause, which was the cause of freedom, he is ultimately victorious.

It is no coincidence that Herodotus establishes a direct relationship between the end of the tyranny in Athens and the help given to the Ionians who were about to rebel, help that determines the aggression of the immense armies of Darius and his son Xerxes. Now, it is not so much a question of judging the historical truth of this story, as of reflecting on the strength of an idea that is independent of the greater or lesser correspondence to the reality of the facts. Perhaps those of my no longer green age remember how left-wing intellectuals, both from the parliamentary and radical left, celebrated the heroic struggle of the Vietcong who defended the freedom of their country against an enemy considered invincible. Today some of them, and those who consider themselves their heirs, have become champions of realpolitik, to the point of suggesting to the Ukrainians massacred by the Russian bombs to lay down their weapons to avoid further bloodshed. They may not be Putinians, but they are certainly the expression of a cynical and hairy pacifism.

A term coined by Roland Barthes comes to mind, the term "Neneism". It consists in establishing two opposites and weighing them against each other so as to reject both: I want neither this nor that. It is a magical procedure, specifies the prince of French semiologists, through which one equates how embarrassing it is to choose to get rid of a reality that does not correspond to one's prejudices. From yesterday's “neither with the State nor with the Red Brigades” to today's “neither with NATO nor with Putin”, our most recent history is full of neneists. Pale stunt doubles of Romain Rolland author, shortly after the start of the Great War, of "Au-dessus de la mêlée" ("Above the fray"), they do not have the courage to assume the first responsibility that Norberto Bobbio attributed to intellectuals : that of preventing the monopoly of force – I am obviously speaking of the Moscow autocrat – from also becoming the monopoly of truth.

On the contrary, old academia caryatids and improvised geopolitical experts preach "neither here nor there", they believe that their task is, precisely, not to get their hands dirty, to look with aristocratic disdain at the dogs that fight ; and perhaps to continue to speculate, predicting misfortunes, on the outcome of the "special military operation". They are those scholars who, professing to be neutral, believe "to float on the waves – Bobbio said – like the lords of the storm, and are rejected, without realizing it, in an uninhabited island".

In the present time, where the supreme values of liberal democracy are at stake, there is no room for third-party (aka anti-Western) positions. You have to choose which side to be on: either here or there. To take up a metaphor dear to Julien Benda, between Michelangelo who accuses Leonardo of his indifference to the misfortunes of Florence, and Leonardo who replies that the study of beauty occupies his whole heart, the self-styled partisans of peace should have no doubts in siding with the sculptor of the Pietà. There is a verse from the "Bellum Civile" of the Latin poet Lucano which reads: "Victrix causa deis placuit / Sed victa Catoni". Its meaning is: Caesar's cause won because it was supported by the gods, while Cato the Uticense lost for having espoused the cause of republican freedom. Does this mean that the vanquished are always wrong just because they are vanquished? But can't today's winner be tomorrow's winner?

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/gli-intellettuali-italiani-e-il-mito-del-vietnam/ on Sat, 25 Jun 2022 05:42:00 +0000.