Pope Francis and Immanuel Kant: which comes first, peace or freedom?

Considerations (of a Crocean Christian) between philosophy and religion on war and peace. Michael the Great's Notepad

From the beginning of his pontificate, Pope Francis' appeals cannot be counted so that peace, that is for him the "absolute good", should prevail over war, that is always for him the "absolute evil". Despite the high and noble magisterium of the pontiff, this absolute evil, however, does not seem eradicatable from human history. This also poses to a non-believer like the writer, but who considers himself a Christian, a question that was first put forward, in its most radical formulation, by Epicurus (341-270 BC) with his famous "equation": "The divinity or wants to abolish evil and cannot; or he can and does not want to; or he doesn't want to or can't; or wants and can. If he wants and cannot, we must admit that he is powerless, which is contrary to the notion of divinity; if she can and does not want, let her be envious, which is equally alien to the divine essence; if she does not want and cannot, let her be both impotent and envious; if he wants and can, the only one that suits his essence, where then do evils come from and why doesn't he abolish them?”.

The response to these objections is known and has ended up prevailing in Christian theology, in Origen's version as in that of Augustine: evil is nothing other than the absence of good ("privatio boni"). But it was above all Augustine who insisted on the congenital corruption that derives, by transmission, from the original sin of the "protoplasts" (i.e. of the "progenitors", Adam and Eve). Congenital corruption which is the mother of a moral evil from which only the unfathomable grace of the Lord frees the predestined.

The modern age knows three great theodicies: that of Leibniz, Spinoza and Malebranche. Although starting from different assumptions, they reach an identical result: God could not have created a world different from the current one. Modern theodicies claimed, therefore, to make evil fully intelligible and justifiable. In a short writing published in 1791, "On the failure of all philosophical attempts in theodicy", Kant considers it execrable that God judges with rules different from those of men, and that what appears bad to us is legitimate for him. According to the author of the three "Criticisms", it is Job's suffering and indignation that are moving; the "words in defense of God", however, irritate and do not console. Kant's demolition of theodicy and the horrors of the "short century" contributed to the crisis of the Augustinian doctrine which denies the reality of evil.

One last consideration. The crisis of the "stop-gap God" (the expression comes from the Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhöffer, hanged by the Nazis in 1945), exacerbated by the trauma of the Shoah, should have dismissed the idea of an instrumental evil that serves to make goodness shine better of a wise alchemist God, who brings good from evil.

****

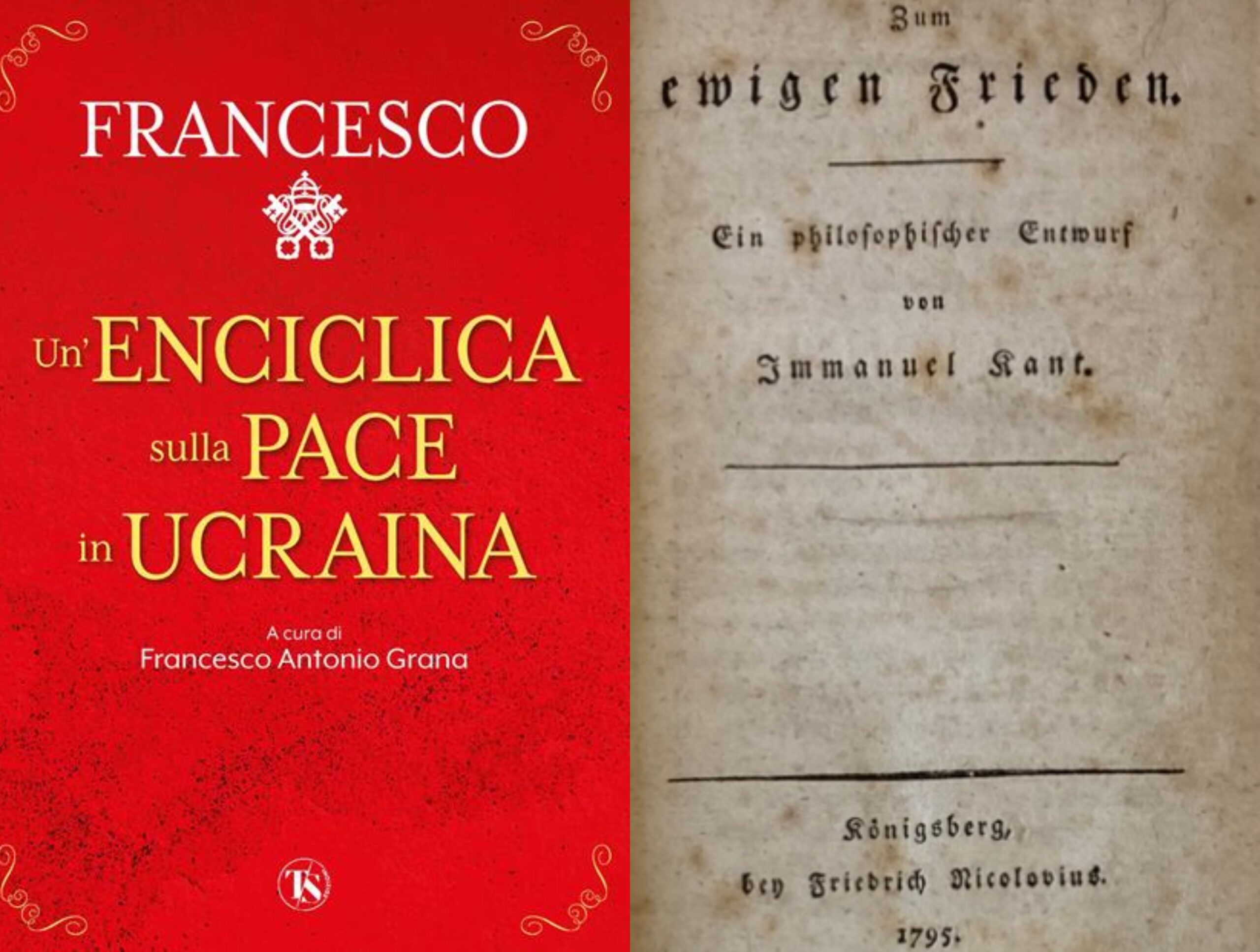

His name is sometimes evoked to claim the quarters of nobility that the doctrine of "peace at any cost" has. In the articles of the most diehard intellectuals of ethical pacifism, however, it is often cited to legitimize a sort of conscientious objection to sending weapons to Ukraine. The name is that of Immanuel Kant , the author of “Zum ewigen Frieden”, known in Italy with the improper but now canonical title, “For perpetual peace” 1795). It is considered one of his most famous and evocative texts, an authentic masterpiece of unparalleled elegance and extraordinary originality. But, unlike pacifist fundamentalism, anchored to the Erasmian assumption that "the most unjust peace is better than the most just of wars", or that peace is the supreme good, to be placed unconditionally before any other value (including freedom), Kant decisively rejects the idea of peace achieved at any price, even at the cost of being built on the "cemetery of freedom". And, although he recognizes war as a "scourge of the human race", he does not consider it an "incurable evil" like the much more feared "tomb of a single dominion". In fact, he warns against the risks of a universal and lasting peace achieved "under a single sovereign", destined to lead to the "most horrible despotism".

However, if the eighteenth-century image of a pacifist Kant is largely unlikely, the specular thesis of a Jacobin Kant is without foundation. His "peace of reason", based on the recognition of the "peaceful contrast between peoples", certainly has very little in common with the naive pacifist utopia which dreams of the extinction of all conflict. Moreover, without prejudice to his undisputed sympathy for republican France, the warnings and fears expressed by the philosopher in various places in "Zum ewigen Frieden" concerned precisely the indiscriminate resort to "peacemaking" war theorized by the most radical wing of the French revolutionaries, convinced supporters of the idea that, on the altar of future peace, any means could be justified, even a war of extermination. The Kantian project of replacing war with law, in short, is sidereal distant both from revolutionary and messianic fundamentalism, for which all means are legitimate in order to obtain the final pacification of the European states under French domination, both by the "peace of love" of Robespierre: of a love, however, destined to triumph fully only after having eliminated by force those that suffocate him.

Unlike Robespierre, Kant's perpetual peace is not the fruit of love between men, nor must it benefit their well-being and happiness, but "it is solely in conformity with law": it is not at all "an ethical final state- religious” nor “an earthly paradise”, but rather the pure “legal regulation of antagonisms”. Animated by a philanthropic, messianic, apocalyptic, expansionist ideology and certain of its rectitude, the French Jacobins instead aimed at the elimination of all antagonism and the universal establishment of a perennial peace – that is, definitive and absolute – through a revolutionary war that would inaugurate , thanks to a final “spasm of violence”, a new era of bliss.

The connection between perpetual peace, the happiness of peoples and the golden age, understood as the ideal condition for the peaceful enjoyment of earthly goods, is completely foreign to Kantian thought, but rather seems to echo, as the former mountaineer Danton had intuited, archaic and never completely forgotten folkloric beliefs in the legendary "Land of Cockaigne": that mythical place where well-being, abundance and pleasure are within everyone's reach. Paradoxical as it may appear, the pacifist Kant on the contrary feared – no less than the "war-mongering" Hegel – the ruinous effects of a "long peace", in which the predominance of "low personal interest", "cowardice" and "softness" ” would have corrupted “the character and mentality of the people”.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/papa-francesco-e-immanuel-kant-viene-prima-la-pace-o-la-liberta/ on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 06:30:29 +0000.