Scandalous avarice

Michael the Great's Notepad

The desire to get rich at any cost, the passion for business, the greed for profit, the pursuit of well-being and material enjoyment are the most common passions in this society. They spread easily to all classes, penetrating even those who had hitherto been more alien to them, and will soon weaken and degrade the entire nation if nothing will stop them.

(Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the Revolution, 1856)

Below a certain amount of money, noted Roland Barthes, a judicial case is always a simple news story. For there to be a scandal, "a modern equivalent of the old treasure, of the trunk full of jewels and sequins" is needed (Che cos'è un scandala, in Miti d'oggi, Einaudi, 1994). An observation that confirms the incomparable critical acumen of the French semiotician. The Qatargate affair, for example, exploded when a few bulging sacks of euros were discovered. It was then that the show of indignation was staged, in which the spectators, in the shadow of the gallery or the stalls, await the apocalypse of the corrupt (not of the corruptors) rather than the verification of the truth. But who are the investigators, witnesses, accusers fighting against? Only against a clique of lobbyists, businessmen, fixers, officials, debatable MPs? In fact, they are also fighting against an invisible enemy. An enemy that must be fought with the weapons of law, not with moralistic appeals to honesty. This enemy is avarice, the most indomitable of the seven deadly sins. In accordance with its rapacious character, it boasts a multiplicity of synonyms: greed, covetousness, covetousness, gluttony, up to some more specific metonymies such as stinginess or simony. Whatever you call it, it is constantly reborn from its own ashes like the Phoenix, the mythological bird of the ancient Egyptians. In a famous page, Max Weber writes that "he was and is found in waiters, doctors, coachmen, artists, cocottes, soldiers, bandits, crusaders, in those who frequent gambling dens, in beggars – one can say: […] in all ages in all countries of the world” (The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 1904-1905).

“Radix omnium malorum avaritia”, St. Paul ruled. But whether a religion associates or distinguishes vice from sin, all of them – from Hinduism to Taoism, from Buddhism to Christianity – agree in considering avarice the most treacherous of our seven demons. In Judaism, long before Sinai and the delivery of the Tablets to Moses, there was Noah with the seven laws, or "mishpathim", presented in the first eleven chapters of the book of Genesis. In the order in which the biblical text lists them, the first "mishpat" or sin is blasphemy, followed by idolatry, theft, murder, illicit sex, perjury, eating meat cut from live animals. Over time many rabbis decided that the most serious of these sins was theft, since all the others depend on theft. Adultery is stealing from a husband or wife. To blaspheme is to steal God's name for vile reasons. To kill is to steal someone's life, and so on. But theft, in turn, was nothing more than a manifestation of the incontinent character of avarice.

In early Christianity, while the corruption of a crumbling empire became more and more oppressive, the maxim of the apostle of Tarsus was often transcribed vertically by the faithful, like an acrostic, like a satirical cartoon on the dissolute customs of Rome:

Radix

omnium

Malorum

Avarice

It was this kind of graphic game that defined avarice more than any other vice, because it was the most social and, by extension, the most political of sins. Later, Aurelius Clement Prudentius (348-413) resumed the Pauline conception of the holy war against the "kingdom of darkness", which quickly became the aesthetic foundation and basic principle of Western art, thought and theology. In fact, we owe an allegorical poem, Psychomachia ("Battle of the soul") to the imaginative inspiration of the Spanish ascetic. It is the story of seven battles, one for each capital vice, and in which each vice has a human form. In a nutshell, after a bloody massacre of slaves, as if to demonstrate her absolute depravity, Avarice tries to corrupt a group of priests devoted to the service of the Lord. Suddenly Reason appears, inciting them to rebel. The unexpected reaction arouses the wrath of Avarice, who promises that she will take by deceit what she cannot conquer by force. Then, however, he changes his attitude and feigns a certain nobility of mind. With the imaginative power of his verses, Prudentius gives avarice a female identity with congenital duplicity. This representation of him became very popular in the medieval religious belief system, in which the primacy of pride, a typical feudal sin, begins to be ousted by greed, a typical bourgeois sin.

In a closed economy, where money circulation was scarce, usurious interest was not yet a big problem. The monasteries provided the majority of the credit needed. It becomes so when the wheel of fortune begins to turn not only for knights and nobles, but also for the merchants of the cities that are buzzing with work and business. The Church is shaken by it. Pope Innocent IV (1195-1254) attributes to the cult of Mammon (symbol of iniquitous wealth) even the scourge of the countryside abandoned by landowners, who were also attracted by those gains which blatantly betrayed the verb of Luke the evangelist: "Mutuum date, nihil indesperantes” (Lending without expecting anything in return).

On the other hand, the Divine Comedy is an anthology of invectives against avarice, described as a she-wolf who "has such a wicked and evil nature / that she never fills the greedy desire, / and after a meal she is hungrier than before" (Hell, canto I). Furthermore, Dante places usurers among the violent because they harassed those who needed the "cursed flower" (the florin, the currency of Florence) for commercial or family needs. The usurers who appear in Hell are above all wealthy bankers: the Gianfigliazzis, the Obriachis, the Scrovegnis. But one thing “the doctrinal execrations were, another the effective reality. In the homilies the rejection of usury was total. In practice, it was opposed with prudence and moderation. It was even tolerated, provided that the interest rate requested was not too much higher than the market rate” (Jacques Le Goff, The stock exchange and life. From the usurer to the banker, Laterza, 2013). A prudence, moderation and tolerance advised by the new values and new lifestyles that were establishing themselves in the nascent mercantile society.

The fifteenth-century humanist Poggio Bracciolini interprets it in a dialogue, De avaritia (1428-1429), which overturns Dante's condemnation. In fact, for the future Florentine Chancellor there is a difference between "avaritia" and "aviditas". Every activity would fail if there were no desire to increase one's wealth and well-being. Every city needs misers who mobilize labor to increase the value of the goods produced. In short, avarice is not a vice but a virtue. A reading of avarice that anticipated the sixteenth-century "century of the Genoese", highly skilled speculators in manipulating everything that was on paper. It was also the century in which the Protestant merchant, "fed on the Bible and the Old Testament, confusing the designs of Providence with the prosperity of his fortune, could pray to God for success in business" (J. Le Goff, Tempo della Chiesa e tempo of the merchant, Einaudi, 1977). It was also the century in which great Flemish painters such as Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder coined new images of avarice, marked by strong realism.

Almost two hundred years later, it is Bernard de Mandeville who sings the praises of avarice, impressed by the prosperity and power of Great Britain. His apologist The Tale of the Bees (1705) was particularly appreciated by Kant, and it can legitimately be argued that it predates utilitarianism. In 1776 Adam Smith published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. which remains one of the most insightful analyzes of how avarice works in a market economy. So much so that it was studied by the founders of game theory, i.e. the science of strategic decisions. In short, with the Scottish philosopher's masterpiece, the bourgeois ethos linked to the success of industrial and financial capitalism promoted by the English Revolutions of the seventeenth century takes shape, while France will abandon monarchical absolutism only with the Revolution of 1789.

As the historian Gabriella Airaldi observes in a learned and compelling essay, it is remarkable that in Genoa, the city of the "lords of money", there is no mask depicting the miser, as instead exists in Venice where, since the sixteenth century, dominates that of Pantalone and “where, not by chance, Shakespeare places his Shylock. However, Venice has a different history, a history of the market and not of finance” (Being miserly. History of possession fever, Marietti 1820, 2021). And yet Carlo Goldoni was Venetian, author of a one-act play, "The Miser" (1756), who revisited Molière's comedy of the same name, performed for the first time in Paris in 1688. In 1833 Balzac chose agrarian France to tell the parable of Eugénie and her father, the elderly winemaker Grandet who got rich thanks to an infallible nose for business and a proverbial avarice. From 1843 is Dickens ' Christmas Carol, which narrates the surreal existence of the stingy banker Ebenezer Scrooge. “My stuff, come with me!” shouts the stingy and swindler Mazzarò in a novel by Giovanni Verga from 1880. In 1933 Otto Dix, the “obscene and degenerate” artist hated by the Nazis, turns avarice into a horrendous hag . And so do Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht with the "Seven deadly sins of the petty bourgeois". Freud too delves into the psychic labyrinth of the miser, with a reference to Luther's "dung of the devil".

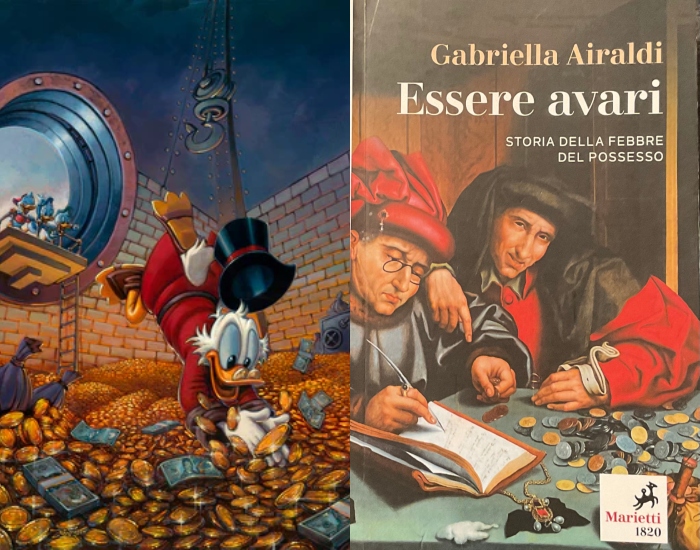

But it's not easy to resist the seduction of money, Grimaldi rightly argues. It has been sung by Pink Floyd, Liza Minnelli and many others to this day. After the war, the American "way of life" fascinated everyone. In 1947 he made his debut in the world of comics and cinema Uncle Scrooge McDuck, or Scrooge McDuck. His biography reflects the dream of every emigrant to whom the States appear as a happy and longed-for destination. McDuck, a poor shoe shiner of Scottish origin (perhaps the choice is not accidental), after many vicissitudes and a thousand trades arrives in the fabulous Klondike of gold seekers. He therefore accumulates enormous wealth that he does not want to share with anyone and which makes him the subject of constant extortion and robbery, forcing him into an unnerving existence. But the world of Scrooge McDuck, now far away, was "the prelude to another America which, together with many successes, also brought with it the story of Gordon Gekko, the New York financier who has now become the symbol of greed without limits which two famous films tell about: 1987's Wall Street and the 2010 sequel Wall Street. Money never sleeps” [Grimaldi]. Says Gekko: “Greed, I can't find a better word, is valid, greed is right, greed works, greed clarifies, penetrates and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed in all its forms: greed for life, for love, for knowledge, for money, has set the forward momentum of all humanity”.

Twenty-three years after this hymn to the "auri sacra fames", in the USA still in shock from the attack on the Twin Towers (we are in early December 2001), the Texan energy giant Enron goes bankrupt. It is the beginning of a kind of American Tangentopoli, which overwhelms the credibility of the most important financial market on the planet. The cracks of other large European companies in Holland, France and England follow closely. A storm that also hits our country, which Mario Draghi comments as follows: "[as if] the market, the savings of Italians, the fate of companies in important sectors of the national economy, had been prey to the arbitrariness and plots of few individuals” (“Final considerations”, Banca d'Italia Shareholders' Meeting, 31 May 2006). And yet the market, as Draghi knew and knows well, is not governed by "pater nosters". After all, even Keynes believed that the most aggressive instincts of the individual could be harmlessly vented on the bank account. However, it is Keynes himself who, participating in a conference held in Madrid in June 1930, concluded his lecture "On the economic prospects for our grandchildren" with moving idealism with these words: […] I therefore see free men returning to principles more solid and authentic than traditional religion and virtue: that avarice is a vice, the exaction of usury a crime, the love of money contemptible […]. We will reevaluate the ends over the means and we will prefer the good to the useful […]. But beware! The time hasn't come yet." Sadly, it still hasn't come even today.

*The paper

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/scandalosa-avarizia/ on Sat, 31 Dec 2022 06:42:44 +0000.