The betrayal of Munich and Winston Churchill’s greatest speeches

Michael the Great's Notepad

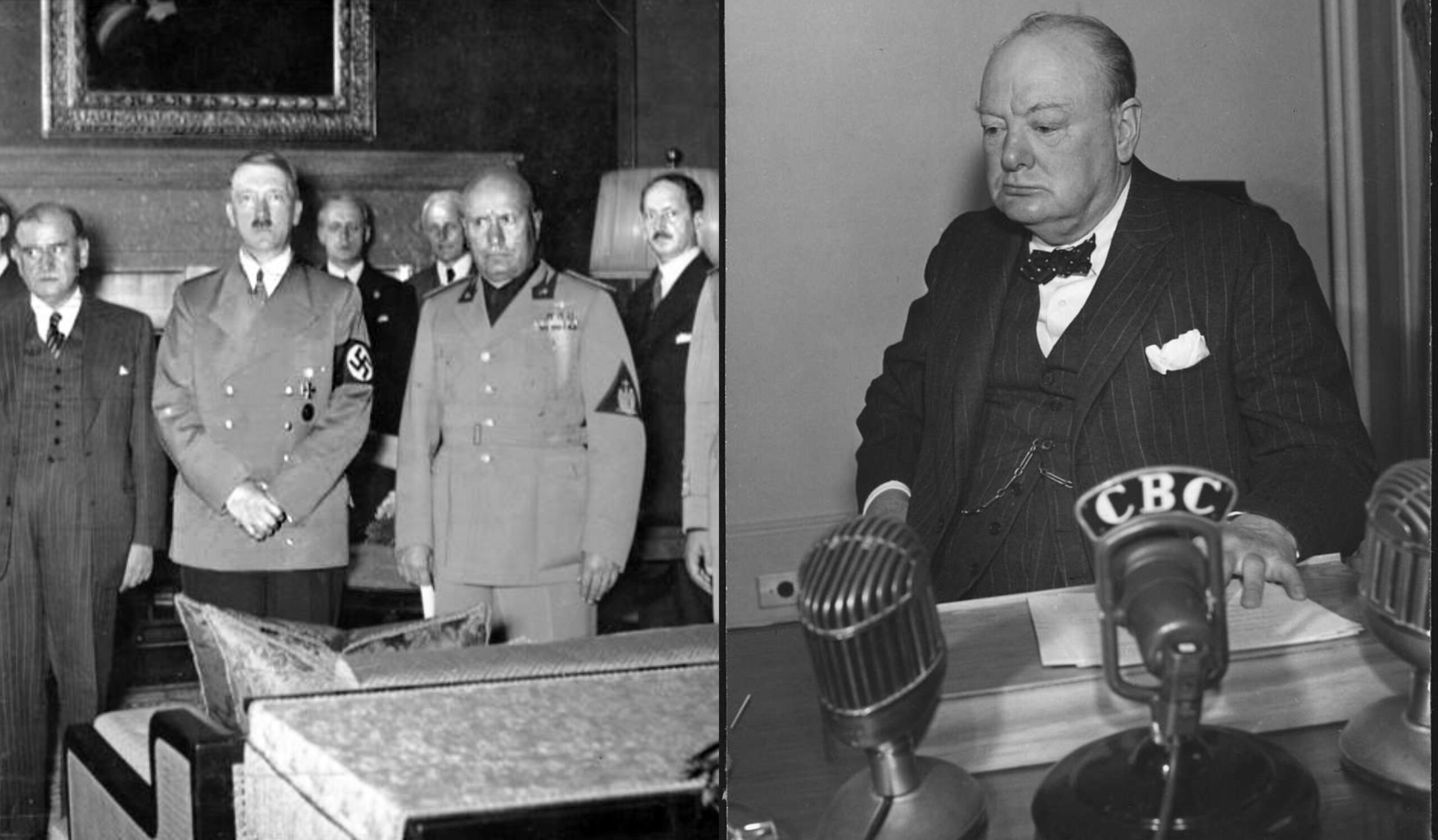

On 29 September 1938 Hitler met the English Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, the French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier and Benito Mussolini in Munich. The following morning they signed an agreement allowing the German army to complete the occupation of the Sudetenland region. Britain and France told the Czechoslovakian government that it could either resist the Nazi invasion alone or surrender and accept the deal. Abandoned by its allies, Czechoslovakia quickly threw in the towel. Upon their return home, Chamberlain and Daladier were greeted by cheering crowds, convinced that a disastrous military conflict with the Third Reich had been avoided and its hegemonic ambitions on our continent had been quelled. In March 1939 the Führer broke the agreement by annexing the whole of Bohemia and Moravia (an about-face known to history as "The Betrayal of Munich").

In October 1939, Emmanuel Mounier published an essay entitled “Les Chrétiens devant le problème de la paix” in the magazine “Esprit”. Published for the first time in Italy in 1958, Castelvecchi (“Christians and Peace”) has recently been reprinted. With a clear allusion to that "betrayal" the philosopher of "personalism" writes: "This pacifism , in September 1938, did not have at heart the justice of the Sudetenland, nor that of the Czechs, nor that of the Treaties, nor that of their victims, nor the injustice of the war, but he had only one obsession: that his dreams as a pensioner would not be interrupted. […] Peace is compromised not only by warmongers but also by the cowardly […]. Is this perhaps the behavior befitting the faithful of a religion whose cornerstone is a God made man on earth?”. They are noble words, the expression of a "Christian realism" siderally distant from the political realism exhibited in imaginative peace plans by some domestic maître à penser.

Late May 1940: Germany was winning the war and Hitler calmly awaited England's surrender. After the defeat at Dunkirk , his days seemed numbered. The rest of the world was silent, with the USSR on the sidelines, the United States far away, Italy and Japan lurking. The great American historian John Lukacs explained why the Führer did not immediately deliver the final blow to the British army: he was awaiting the outcome of the confrontation, in the conservative party and in the government, between the Foreign Minister Edward Halifax, Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister whom Winston Churchill had replaced after the Nazi occupation of Norway, and Churchill himself (“Five Days in London”, Corbaccio, 2001). Halifax and Chamberlain were in favor of finding a diplomatic solution to the conflict that would allow a peace agreement with the Third Reich. Churchill, on the other hand, was against any idea of appeasement with the Germans. On May 28, when news arrived that Belgium had surrendered, he declared, knocking out his internal enemies: “Our only hope is victory, or we will cease to be a state.”

With this granitic moral and political conviction he delivered the "greatest speeches", the great speeches that animated the resistance against Nazism until its defeat. There is no doubt that Europe and the whole world should be more grateful to the eminent statesman, who led Great Britain to victory against the Axis powers, than to a cowardly politician like Chamberlain or a snobbish dubious man like Lord Halifax .

Historical similarities are always arbitrary and, as Antonio Gramsci said, if history is a teacher of life it has always had terrible students. However, remembering lessons from the past can sometimes be helpful in better understanding the present.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/il-tradimento-di-monaco-e-i-greatest-speeches-di-winston-churchill/ on Sat, 21 Oct 2023 05:15:32 +0000.