The Betrayal of the Clerics by Julien Benda

Michael the Great's Notepad

Shortly before his death (2012), Eric Hobsbawm observed with a hint of nostalgia that the era in which “intellectuals were the main public face of political opposition now belongs to the past.[…] In a society dominated by the incessant mass entertainment, activists looking for useful supporters of good causes prefer to turn to famous actors or rock musicians rather than intellectuals […]. We live in a new era, at least until the universal noise of self-expression via Facebook and the egalitarian ideals of the Internet have had their full effect on the public scene” (Intellectuals: Role, Function and Paradox, in The End of Culture. Essay on a century in identity crisis, Rizzoli, 2013).

The British historian of the "short century" thus described the decline of one of the central figures of the twentieth century, whether he was in the service of power, organic to a party, a "maverick". But the intellectual has always been a strange beast. In fact, what is his job? Luciano Bianciardi, intolerant of any cultural establishment, after asking himself this question in his "Six lessons for becoming an intellectual, dedicated in particular to young people without talent" (published in 1967 in the ABC magazine), concluded that it was an indefinable profession . For the author of Vita agra the true intellectual, ultimately, is (or should be) a slave to everyone and a servant to no one. But the fact that the intellectual Hobsbawm regrets is also a dying breed in the time of social networks, overwhelmed by the course of history and new forms of politics, is certainly nothing new.

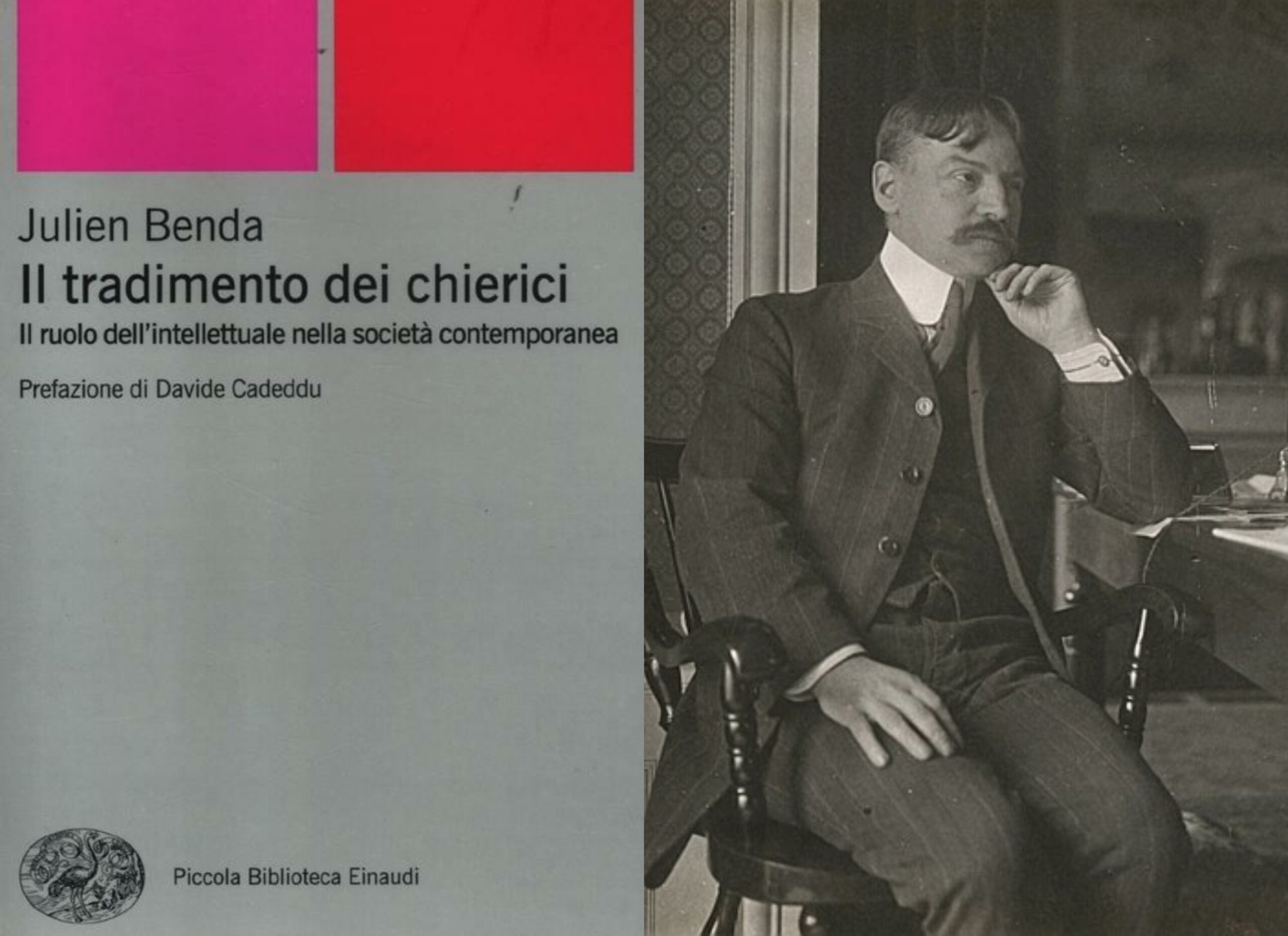

Almost a century has passed since the publication of Julien Benda's pamphlet , The Betrayal of the Clerics (1927), in which the French philosopher denounced the subservience of the intellectual to the interests of the dominant classes (or, rather, of their political representatives). He defended his image as a guardian of the values of truth and justice, alien to any partisan involvement that could distract him from his tasks of rational education. In this regard, he recalls the great names of the past who remained alien to political passions, unlike those (Theodor Mommsen, Maurice Barrès, Charles Maurras, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Rudyard Kipling) who had instead challenged them with the "thirst for results immediate".

It is in particular the patriotic passion that Benda argues most bitterly with, and he attributes its primogeniture to the German intellectuals between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But "the humiliation of the universal" also occurred to the advantage of the class, for which Georges Sorel's Réflexions sur la violence (1906) are largely responsible, a lesson in hatred that is found in parallel in Italian fascism and Bolshevism Russian. Only in some circumstances, here the reference to the Dreyfus affair is explicit, are intellectuals allowed to enter the political arena without failing in their function. In general, however, the correct course of action for the "cleric" in the modern world is to protest verbally and drink hemlock when the State orders it. Any other action is treason.

The century of betrayals is the title of a book by Marcello Flores, in which the debate sparked by Benda's theses is masterfully reconstructed (il Mulino, 2017). The one contesting them was a young communist novelist who, in 1931, had published a text that would make him famous, Aden Arabie, which was followed the following year by Les chiens de garde, his response to La Trahison des clercs. Nizan's is in some ways the first coherent formulation of a theory of intellectual commitment. For the twenty-seven-year-old writer from Tours, referring to the eternal values of truth and justice without talking about colonialism, war, industrialization, unemployment, love, death and politics, that is, all the problems that beset the majority of the planet's inhabitants, was just an attempt to obscure the miseries of contemporary reality. It was necessary to take sides: with the oppressed or against. Reversing Benda's argument, for him the "watchdogs" are the intellectuals who refuse to get their hands dirty and defend the privileges and wealth of the bourgeoisie.

Around the mid-1930s the theme of the commitment of intellectuals was at the center of a series of events of international importance. In September 1934 the first congress of Soviet writers took place, attended – among others – by the French André Malraux and Louis Aragon together with Nizan himself, the Spaniard Rafael Alberti, the American Mike Gould, although the main talks were held by two of the highest leaders of the CPSU, Nikolai Bukharin and Andrej Zhdanov, one on the way to a dramatic decline and the other on an unstoppable rise.

However, it is the congress that opened in Paris on 21 June 1935, dedicated to the "defense of culture" in the face of the advance of Nazi-fascism in Europe, that became the very symbol of that engagement that would be Jean Paul Sartre's mantra. There is a lack of supporters of Trotskyism and conservative-oriented personalities, such as François Mauriac and Henry de Montherlant. The totality of those present, however, constituted a prestigious assembly. It was Gide, who had recently converted to communism and was destined to abandon it sensationally a few years later, who inaugurated the meetings.

Benda, who would later become an intransigent defender of the most tragic phase of Stalinism, contrasted communism with Western civilization as irreconcilable. Nizan harshly contested this. Only Robert Musil asks to be able to "escape the demands" of politics, inviting colleagues to learn the "noble feminine art of not indulging". The Austrian playwright, author of one of the milestones of literature, The Man Without Qualities, also invites freedom, meaning by it a psychological idea, audacity, restlessness of the spirit, the pleasure of research, frankness and the sense of responsibility, because "no culture can be founded on an oblique relationship with the truth".

The question of truth was taken up with leonine courage (in that context) by Gaetano Salvemini, then a professor at Harvard. It is he who raises the "Serge case", creating great embarrassment in the audience. At the end of his speech, causing scandal and disapproval, the illustrious Italian anti-fascist states: “I wouldn't feel entitled to protest against the Gestapo and the fascist Ovra if I tried to forget that a Soviet political police exists. In Germany there are concentration camps, in Italy there are islands used as places of punishment, and in Soviet Russia there is Siberia […] – it is in Russia that Victor Serge [follower of Leon Trotsky, accused of anti-Soviet activities] is a prisoner […] -one can understand the necessity of the current Russian totalitarian state on condition that one hopes for its evolution towards freer forms, but it must be said and it cannot be celebrated as the ideal of human freedom”.

For the left-wing cultural milieu dazzled by the "sol of the future", the myth of the USSR seemed like a good ploy to preserve its revolutionary faith, even at the cost of hiding the reality: that of a grandiose utopia of emancipation of work that was turning into its most suffocating and bureaucratic coercive apparatus. The intellectuality that had made the vocabulary of Marxism-Leninism its own had a new period of glory between the end of the Second World War and the collapse of the Soviet empire, that is, during the massive mobilizations for nuclear disarmament and against the invasion of Vietnam . Subsequently, trust in the unstoppable march of progress gave way to the fear of an inevitable environmental catastrophe, seen as the perverse fruit of unregulated globalization. Despite this, it cannot be said that intellectuals in our country, whatever their tendency, show themselves to be very concerned about the future of humanity. A little bad. After all, it would be enough if they didn't turn into acrobats in the equestrian circus that performs every day on the national political scene.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/il-tradimento-dei-chierici-di-julien-benda/ on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 06:30:45 +0000.