The delusions of freedom

Michael the Great's Notepad

The poor fortune of liberal ideas in our country is still subject to the reservation of Guido De Ruggiero, who considered Italian liberalism only the reflection of foreign doctrines. The Neapolitan philosopher attributed his weakness to the concurrence of multiple causes. Secular ethics had been depressed because Italy had known the Counter-Reformation without the Reform. The formation of a national citizenship had been hindered by municipalism in the North and by enslavement to foreigners in the South. The industrial revolution had given birth only in some areas to an autonomous and productive bourgeoisie, i.e. a middle class capable of sponsoring the general interest (History of European liberalism, 1925). Ancient delays that serve to explain how, not having found a fertile womb in civil society, "Italian liberalism has developed in itself an inclination to detach itself from Italy as it is" (Valerio Zanone, L'età liberale. Democrazia e capitalismo nella open society, Rizzoli, 1997). And which also serve to explain the reasons why the liberal ruling class has not stabilized into a constitutional party on the British model; and how in the same liberal statesmen – from Cavour to Giovanni Giolitti – the awareness of swimming perpetually against the tide was explicit.

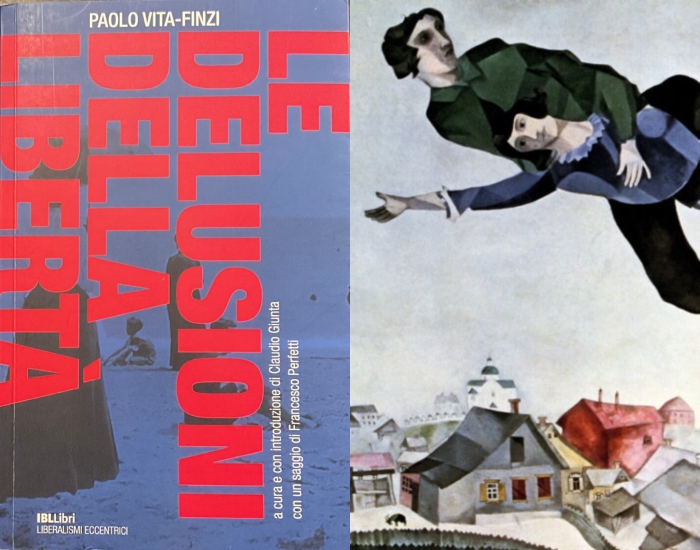

It should therefore come as no surprise that in the Italy of the "short century" liberal ideas were defended and disseminated above all by secluded intellectual figures, extraneous to academic and editorial consortia. One of these figures, familiar only to a small circle of experts, is certainly that of Paolo Vita-Finzi (1899-1986). Perhaps it will be a little less so thanks to the reprint – embellished with two masterful introductory essays by Francesco Perfetti and Claudio Giunta – of one of his most significant texts, The delusions of freedom ( IBLLibri , January 2023). Published for the first time in 1961 thanks to the interest of Giuseppe Prezzolini at the publisher Vallecchi, it collects eighteen short writings that appeared between 1954 and 1958 in Mario Pannunzio's weekly "Il Mondo". As Giunta points out, they are surprisingly current. In fact, reflecting on the attitude held by Italian and French intellectuals at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, they touch on themes that remain at the center of public debate: distrust of parliamentary democracy; impatience with its procedures, which slow down the decision-making process; the hatred for the conspiratorial elites and, symmetrically, the almost messianic devotion to the people, perhaps by those who are alien to the people by wealth and culture; the reduction of the political question to a moral question.

Yet Vita-Finzi was not a scholar by profession. Born in Turin into a Jewish upper middle class family, he fought as a volunteer on the Piave front in the last months of the Great War. Upon his return, he studied and worked in the Turin of the red two-year period, met Piero Gobetti and Antonio Gramsci, but without falling under the fascination of either the former or the latter. Raised in the cult of the Risorgimento, he had no sympathy for those who glorified factory councils and the storming of the Winter Palace. A friend of Piero Sraffa, he had had the opportunity to meet and visit the founder of "Ordine Nuovo" in the economist's home. In his memoirs he portrays it mercilessly but not without admiration: “Gramsci had always reminded me of a black ember, or something similar. He was hunchbacked, perhaps one meter forty tall, with an enormous head planted on a stunted little body: his eyes were beautiful and large, sparkling with intelligence, his laughter quick and sarcastic, his clothes very careless. Sometimes it seemed to me that he had something of Marat” (Distant days. Notes and memories, il Mulino, 1989).

Equally sharp is the judgment on the "cherubic Jansenist": "If I admired Gobetti's intelligence and vertiginous activity, his ideas had always left me perplexed: however elastic the word 'liberal' is, I could not persuade myself that the revolution Russia was an act of liberalism" (ibid.). The truth – warns Perfetti – is that the liberalism of Vita-Finzi was starkly distant from the revolutionary impulses and Jacobin enthusiasms of the two "Dioscuri", from a vision of the spontaneity of the masses as the demiurge of "fulfilled socialism". In this sense, it is remarkable how utopians of all ages describe their imaginary societies in minute detail. Plato in the Republic prescribes meticulous rules to regulate the sexual relations allowed for procreation. Thomas More in Utopia deals with the clothing of the islanders to distinguish married from celibate. Tommaso Campanella in the darkness of the prison dreams of a City of the Sun in which the names of the inhabitants are decided by a magistrate, the Metaphysician. In short, at the basis of all utopias there is a model of perfect society which, in order to be such, needs to annihilate the freedom of individuals. Vita-Finzi was well aware of this when, retracing his youthful acquaintances, he mentions his political creed at the time in these terms: "[…] influenced above all by the lessons of Luigi Einaudi […], I was a lib-lab, a liberal slightly in favor of moderate social reforms. They say that at twenty you have to be an extremist in order to be conservative at fifty: then I am an anomalous case, and I almost blush for having been such a respectable twenty-year-old, so juste milieu, so little Sturm und Drang” (Ivi).

In 1938 the racial laws forced him to abandon his diplomatic career, which began in 1924 with stops in the offices of Düsseldorf, Sfax, Tblisi, Rosario, Sidney. He then moved to Buenos Aires, where he directed a magazine, "Domani", a point of reference for the Italian anti-fascists sheltered in the Americas, in which Stefan Zweig, HGWells, Ernesto Sábato, Jorge Luis Borges collaborated. Returning to Italy in 1947, he returned to the ranks of the Foreign Ministry: he was consul in London, then minister plenipotentiary in Finland, then ambassador to Norway and Hungary. In this long wandering, endowed with an extraordinary erudition and master of four foreign languages (French, German, English and Russian), he is very active as a publicist with elzeviri, travel reports, comments on international politics. Almost all stays abroad offer him ideas for writing. He dedicates the journalistic correspondences for the "Corriere Mercantile" to Weimar Germany. From the Argentinian experience derives the essay Perón myth and reality (1973). In 1972 he published Land and Freedom in Russia, in 1975 the Caucasian Diary, in 1980 Half President. The presidential election in the United States.

Of this rich and heterogeneous library The delusions of freedom is the most militant book, the one aimed at the "unconscious precursors" of fascism. Its genesis dates back to the reading of the Histoire de quatre ans, a fictional political story by Daniel Halévy (1903). He was a leading exponent of the transalpine intellectuality, collaborator of the literary periodical "La Revue Blanche" -which boasted the signatures of Proust and Gide, Apollinaire and Debussy- and of Charles Peguy's "Cahiers de la Quinzaine". After the outbreak of the Dreyfus affair (1894), which had split France between guilty and innocent, both Halévy and Peguy had sided with the latter. In reality, both had not failed to express doubts about that "power of the crowd" – and therefore about democracy itself – which another conservative liberal, Gustave Le Bon, had denounced in his famous pamphlet of 1895. Not by chance with them Vita-Finzi opens its gallery of "restless spirits". From the ranks of Dreyfus' defenders came Georges Sorel, even if he had nothing to do with the liberal tradition. Their portraits are joined by those of other protagonists of the cultural scene of the time, such as Émile Faguet, author of Le culte de l'incompetence (1910), and Robert de Jouvenel, author of La République des Camarades (1914). They were characters not close to the reactionary circles of "Action Française", such as Charles Maurras, or to the Bonapartist ones, such as Maurice Barrès, but rather intellectuals of various backgrounds, who let themselves be seduced now (on the left) by the idolatry of the nation, now (on right) from that of the strong man.

Despite the impressive documentation available to Vita-Finzi, the synthesis – Giunta claims- has a cost: complex thinkers such as Vilfredo Pareto, Gaetano Mosca, Giuseppe Rensi, Benedetto Croce, are summarized in a few pages, and exclusively in the perspective of their affiliation to the club of pioneers of totalitarianism but, beyond the criticisms that can be leveled at some too peremptory judgments, The delusions of freedom – with its subtle and ironic skepticism and with its political realism which invites us to distrust false prophets and dreamers of despotic societies- remains an exemplary text of contemporary Italian liberalism. That it was important for the understanding of the parable of fascism immediately became clear to leading personalities of communist and, more generally, progressive culture. Even Palmiro Togliatti (with the pseudonym of Roderigo di Castiglia) reviewed him in a long article in "Rinascita", the official magazine of the PCI. Delio Cantimori did the same in the magazine "Itinerari" (May 1961). Both the leader of Botteghe Oscure and the historian of the Normale di Pisa had appreciated the pages on the "anti-democratic and anti-parliamentary" Croce and on those revolutionary trade unionists in whom one could already glimpse "chrysalis of hierarchs". Four years later Mussolini the Revolutionary (Einaudi, 1965) was released, the first volume of the monumental biography of the Duce by Renzo De Felice, who, quoting some passages from Vita-Finzi's work, implicitly recognized its historiographical value. From that moment on it was no longer possible to question the fact that in the family tree of fascism there were flourishing branches both to the right and to the left.

In the essay Gli intellectuals and fascism (1968), the Turin diplomat resumed the thread of the discourse: “The popular fascism of 1919-20, 'tending to be republican' and anti-clerical, was very different from the strong-handed totalitarian regime of twenty years later; it is easy to understand how some intellectuals may have been initially attracted by it and then rejected it”. These are words that also constitute a kind of self-defense, since the ambiguity towards "tendingly republican" fascism was also his, he too left for Spain to fight alongside Franco's supporters. And he will bitterly recall that participation, which would later be harshly reproached. As a civil servant, his loyalty to the country was, for a period of his professional life, also loyalty to the fascist state. He went through "that process, common to a large part of Italian Jews, of adaptation to a regime which, despite its authoritarian involution, seemed to exclude the risk of anti-Semitic degeneration: that regime, to understand, where Mussolini, in conversation with Emil Ludwig, exalted the national virtues of the Jews and underlined the profound relationship between Judaism and the Risorgimento, between Zionism and the Italian homeland” (Giovanni Spadolini, Paolo Vita-Finzi between history and diplomacy in sixty years of Italian life, Fondazione Nuova Antologia, 1988).

In the early 1960s, Le Delusions of Liberty had, as has been said, a fair amount of notoriety. Today it should be read as a valuable analysis of moods and ideologies which, like a karst river, resurface in the history of European civilization. However, that analysis contains a warning that is also valid in this third decade of the third millennium. Suffice it to quote the following passage: “Demos is the enemy of competence, and that is of the specialization of functions, because 'he wants to do everything by himself, without intermediaries'; his ideal would be direct government as in Athens, what Rousseau called 'democracy'. From time to time he entertains the idea of an imperative mandate, which would transform the people's representatives into mere commission agents […]. And perforce it must rely on those people who have few personal ideas, mediocre education and no other resources outside of a political career, so that they are inclined on the one hand, and forced on the other to interpret the desires and follow the passions of the crowd ”. How can we fail to think of the success enjoyed by neo-populist movements and sovereign parties (those who want to put things back in order) in our house?

During the "Trimalchionis Dinner", the only large surviving fragment of Petronius' Satyricon, the guests – enriched freedmen, corrupt municipal officials, vain and tyrannical wives – discuss politics amidst sumptuous dishes and awkward poetic performances by the host and culture, lamenting the decadence of customs in the Neronian era. At a certain point of the lavish banquet, Echione, a ragpicker, takes the floor. A profession which at the time had a respected social function. In Rome, in fact, the "collegium centonarum" (a sort of association of firefighters) used rags ("centones") to put out fires. Addressing the only intellectual present at the symposium, the rhetorician Agamemnon, Echion asks him in his ungrammatical language: "Quia tu, qui potes loquere, non loquis?" (Why, you who know how to speak, don't you speak?). Today the same question should be asked of the intellectuals who, in the face of ruthless and proud, intolerant and illiberal autocracies, have chosen the path, if not of complicity, of silence: "Why are you silent? Out of cowardice or out of convenience?”

*The paper

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/le-delusioni-della-liberta/ on Sat, 06 May 2023 05:19:58 +0000.