The drop in inflation is not thanks to the ECB

The fall in inflation does not depend on ECB rates. The analysis by Ugo Arrigo and Giacomo Di Foggia for Lavoce.info

Over the past two years, the European Central Bank has had to deal with the problem of rapidly rising and, subsequently, high inflation for the first time in its history. Even if the acute phase of the problem manifested itself during 2022, with the Russian gas crisis, the Euroarea trend inflation rate had already reached 3 percent in July 2021 and 5 percent in December, a significantly higher than the 2 percent target.

In July 2022, when the ECB decided on the first of ten consecutive increases in its rates, inflation was almost 9 percent, before reaching a peak of 10.6 percent in October. In the twelve months that have passed since then, however, it has continuously reduced until reaching 2.9 percent in October 2023, the value of August 2021. But in that month, with inflation already growing for a year and a persistently good dynamic of GDP, the main ECB rate was at 0.5 percent, while now, with inflation falling rapidly and economic growth having completely disappeared, with real GDP at the level of a year ago, the rate is at 4.5 percent one hundred, four points above.

Two questions

These numbers raise two questions, the first prospective and the second retrospective.

The first is whether current monetary policy is not excessively restrictive, generating or risking generating significant costs in terms of recession compared to the limited or non-existent benefits of further anti-inflationary pressure.

The second question is whether inflation actually returned during 2023 as a result of the restrictive monetary policy and not due to the exhaustion of the initial push generated by the import prices of energy goods. Is it possible that monetary policy was so quickly and surprisingly effective?

The first question does not appear to be present in the assessments of the ECB board, expressed after the meeting in Athens at the end of October. In fact, the Central Bank appears to still fear inflation and, although it does not deem it necessary to insist further in a restrictive sense, it believes that current rates are at such a level that, if "maintained for a sufficiently long duration", they will be able to give "an important contribution" to mitigating the inflationary phenomenon. Therefore, the start of a decline in rates in the short term is categorically excluded. Meanwhile, the real economies of the Eurozone countries are languishing, with the area's GDP stuck at the level of a year ago and that of the large German economy preceded by a minus sign.

Regarding the second question, the ECB's chief economist explained in Athens that, based on the macroeconomic models used, the full manifestation of the effects of monetary policy is expected within a two-year period and therefore by 2025. The statement is consistent with the vast literature on monetary policy delays and their variability, started with Friedman's contributions in the 1960s. But, if the effects have yet to manifest themselves, what has happened so far? We are certain that recent inflation is not a very different phenomenon from that fought for a long time in the Seventies and Eighties, the latter a "one shot" event, while the other was a long-term inflation, fueled by the spiral wage prices and at the time counteracted by restrictive monetary policies, effective precisely because they lasted for a long time?

The limits of the trend rate

What is certain is that the measurement of inflation based on the trend rate was suitable for that era, as it was applied to a phenomenon that persisted without undergoing sudden changes. However, it is inadequate to record the change in trend when it occurs in a short period of time. The trend rate tells us how much the prices have changed in percentage in twelve months, but it does not inform us about what exactly happened in the period: they grew more in the first months and then stopped, or they are even decreasing, or it is time who run?

Emblematic in this regard is the case of Italian inflation, measured through the Nic index of the entire community: in September the trend was at 5.3 percent, but in October it collapsed, reaching 1.8 percent. What happened during the year did not require the most recent data to interpret. In fact, the last significant increase in prices was in October 2022, equal to 3.5 percent on the previous month, in the following eleven months prices no longer grew, totaling an overall +1.9 percent, less than two tenths on average per month, a speed in line with the ECB's 2 percent target. So, how do we answer the question of whether inflation was high in recent months? Looking at the trend it was high, but using only the trend is wrong. In reality, Italian inflation has already been low in the last eleven months, although we had to wait until the twelfth for the trend rate to realize this.

The ECB also relies on the trend to measure inflation and decide its policies. In doing so, however, he behaves like a doctor who measures the temperature of his patients with a particular thermometer, capable of certifying whether there has been a fever in the last month, but not of dating it, of saying whether it occurred four weeks ago. ago and then disappeared or if it is currently ongoing. So how can you be sure that you are administering the right medicine at the correct times and in the correct doses?

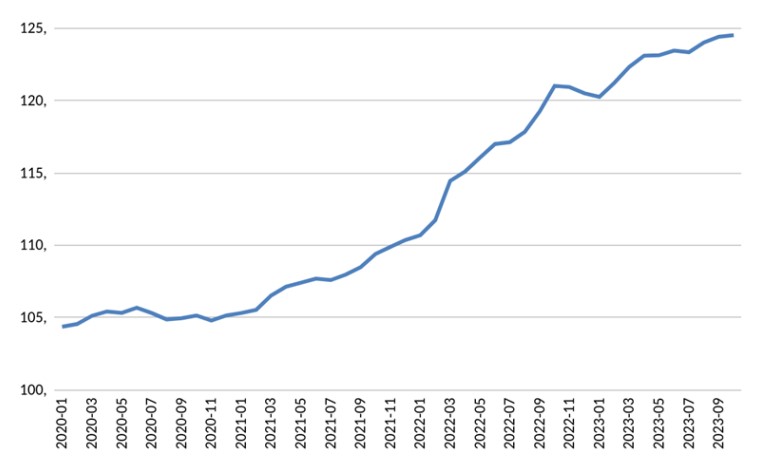

If we want to know the actual price trend we must observe the precise trajectory, obtaining a segmented trend by observing their index number (alternatively using annualized monthly rates as long as they are calculated on a seasonally adjusted index). Based on figure 1 we then see that in the last four years consumer prices in the Euroarea have traveled at very different speeds in four different sub-periods, each of different duration:

- throughout 2020, the first year of Covid, and until February 2021, the price index remained stable;

- from March 2021 prices start to grow again, and until January 2022, the month before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, they travel at an annualized rate of just over 5 percent. During this period there was no change in ECB rates;

- from February 2022 inflation accelerates and in the nine months ending in the following October consumer prices increase overall by 9.3 percent, corresponding to an annualized rate of 12.6 percent. In this period, ECB rates remain stable until July, the month in which the main rate is raised from zero to 0.5 percent, before rising to 1.25 percent in September;

- in the following twelve months the speed of price growth reduces drastically, starting in November 2022, and drops to 3.5 percent annualized in the first of the two semesters and to 2.3 percent in the second, a value compatible with the objective of 2 percent of the ECB.

In the last twelve months, however, the ECB's restrictive monetary policy has intensified and the main rate rose to 2 percent in November 2022 and then, in three successive stages, to 3.50 percent in March 2023 and finally, in four more stages, to 4.5 percent last September. Two thirds of the overall increase over time were decided by the ECB when the speed of price growth had drastically reduced and the inflation phenomenon was spontaneously returning to normality.

If the treatment did not precede the recovery but, as it seems, largely followed it, it cannot have been the cause. How is it possible, in fact, that monetary medicine has erased the disease of inflation in just four months from the start of the administration, which took place in very mild doses from July 2022, when all the studies on the delays in monetary policy indicate times that are of multiples? The theory suggested here that the ECB's monetary policy was excessively restrictive and untimely requires further investigation that goes well beyond this brief note. However, they are necessary, considering that if medicine were now devoid of useful remedies for the no longer existing disease it claims to cure, it would have important side effects in terms of economic recession, probable unemployment and growth in the burden of debt, both private and public, which can only be avoided with a prompt rethinking of current monetary policy.

(Article published on lavoce.info )

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/economia/calo-inflazione-bce/ on Sat, 25 Nov 2023 06:22:21 +0000.