The Jews and the genesis of mercantile society according to Montesquieu

The Notepad of Michael the Great

In the Spirit of the Laws of Montesquieu (1748), the Jews acted as pioneers in the transformation of trade from a despised activity, associated with usury and pawnbroking, to a worthy and esteemed profession. Around the period of the first transoceanic voyages – he writes – trade ceased to be "only the profession of low people" and therefore the exclusive field of "a nation then covered with infamy" (and here he means the Jews), and "returned, for so to speak in the bosom of probity ”(Book XXI, chap. 20).

In this context, for him the descendants of Abraham are at the head of an authentic political and cultural revolution, for which, for the first time, trade "could evade violence". How did they trigger this colossal change and move Europe towards a modern, secure and secular mercantile society? To this complex question Montesquieu gives an answer that is only apparently simple: “they invented the exchange letters”.

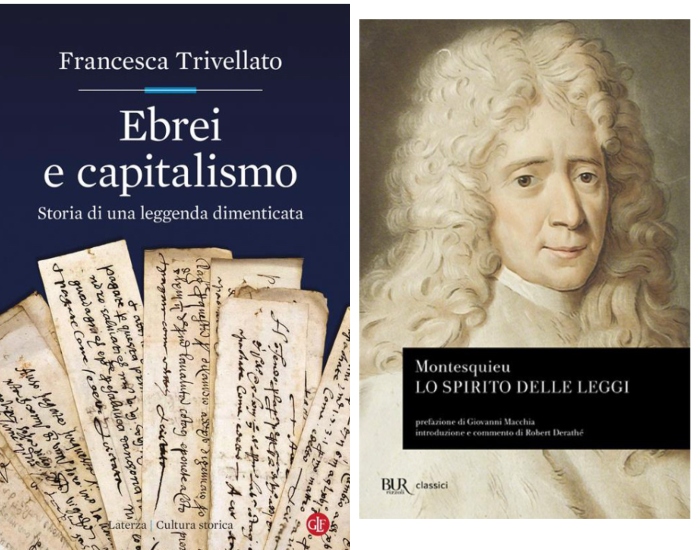

Most of the studies on the French thinker gloss over the meaning of this statement, says Francesca Trivellato in a volume of supreme erudition: Jews and capitalism. Story of a forgotten legend (Laterza, 2021). According to the Princeton professor, exchange letters, or bills of exchange, represented in pre-industrial Europe what constitutes the most sophisticated financial securities in today's capitalist society. Founded at the end of the 13th century to facilitate long-distance trade, they made it possible to transfer funds abroad, eliminating the risks associated with the transport of gold and silver.

Over time they became not only means of payment, but also instruments of speculation. Scams, subterfuges, opacity: these fears for the improper use of bills led theologians to develop rigid schemes to separate the lawful ones from the illicit ones, because they broke the prohibitions against usury. Faced with such uncertainty, resorting to the Christian repertoire of the alleged Jewish credit oligopoly was almost a conditioned reflex.

Thus it was that in the mid-seventeenth century, when the circulation of exchange letters reached its peak, the idea began to emerge that they had been invented – together with insurance policies – by Jews expelled from France during the Middle Ages, anxious to save their riches. A legend, in fact, on the one hand favored by the invisibility of bills of exchange, which moved sums of money by abstracting the monetary value from the material one; and, on the other hand, by the invisibility of the Jews, perceived as a widespread and influential presence but also hidden and indecipherable. A legend, moreover, which owes its international resonance to a text inexplicably neglected by specialists: Le us et coustumes de la mer , a collection of maritime law regulations edited by Étienne Cleirac and published in Bordeaux in 1647.

His Middle Ages are a mixture of reality and fiction. As Trivellato recalls, at that time it was known that ship insurance and bills of exchange were the prerogative of the great Christian merchant-bankers, that is, of the ruling class of the Italian and Northern European municipalities. At the time, Jewish lenders mostly limited themselves to lending to the poor in exchange for pledges and to princes in exchange for the right to reside, albeit with many restrictions, in the state.

The late medieval Jewish bankers ignited Cleirac's imagination as he saw in them the embodiment of overt usurers ("usurarii manifest"), those who lent in public, holding shops in designated spaces, wearing distinctive signs on their clothes, not unlike prostitutes. Cleirac's image of Jews was a prisoner of the past, but her success was due to the widespread concern among her contemporaries about the growing impersonality of market exchanges, a phenomenon that threatened to crumble established social hierarchies and forms of ancient authority, if not divine inspiration.

With Montesquieu, therefore, the invention attributed to the traitors of Christ becomes instead a symbol of modernity. A despot, perhaps to appease anti-Jewish popular sentiments, could be tempted to confiscate land, houses, ingots or goods, but certainly not pieces of paper that he was unable to redeem. Once limited in their power to plunder, the sovereigns had no choice but to behave "with greater wisdom than they would have thought themselves"; thus, finally, Europe was able to begin "to heal from Machiavellianism and it will continue to heal every day".

Meanwhile, still according to Montesquieu, the Church , which equated trade with "bad faith", lost its grip on society and "theologians were forced to reduce their principles". With the rise of the spirit of commerce, moderation triumphed in the spheres of government and social mores: "It is fortunate for men to find themselves in such a position that, while passions inspire them to be evil, their interest is do not be "(XXI, 20).

Montesquieu's interpretation of the genesis of mercantile society exerted a strong influence in France and abroad, providing the most authoritative formulation of the "doux commerce" theory: "Commerce heals from destructive prejudices, and it is almost a general maxim that wherever there are mild customs, there is trade; and that wherever there is trade, there are mild customs "(XX, chap.1). Not by chance, after the publication of the Spirit of the Laws , the bill began to appear alongside the three great inventions – the press, the compass and gunpowder – which, in the wake of Francesco Bacon, were considered the midwives of the modern world.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/gli-ebrei-e-la-genesi-della-societa-mercantile-secondo-montesquieu/ on Sat, 25 Dec 2021 07:21:53 +0000.