The season of the majority: a generous illusion

Michael the Great's Notepad

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Italian futurist avant-garde exalted variety because it was marvelous and eccentric, anti-intellectual and popular, capable of astounding, entertaining, exciting, duping spectators with the speed and sensationalism of its message. The theater of surprise, as the manifesto signed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Francesco Cangiullo in 1921 headlined, therefore had to throw away any elitist dross and become "alogical". Artifice, comedy, unpredictability, meager texts and insignificant characters were the canons and values of Futurist dramaturgy. In 1961 Martin Esslin published The Theater of the Absurd, where the names of Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Genet stand out, progenitors of a literary genre famous for its grotesque humor, its surreal atmospheres, its repetitive, fragmented, devoid of of sense. Well, in the eighteenth legislature, one of the most messed up in republican history, both forms of entertainment alternated without stopping.

The nineteenth risks tracing his misadventures, thanks to a reckless electoral law, which has encouraged the search for spurious alliances supported by contradictory programmes. This confirms that the thirty years of the "Italian majority" represented, in its variegated "bastarde" versions, a textbook example of heterogeneity of ends. In fact, it has not stabilized the political framework, which has suffered multiple and sudden setbacks. He further parceled out the representation. It has tribalized, not civilized, the competition between parties and factions. It has favored "transformative behaviors and the formation of composite and transversal majorities, different from those declared to the voters" (Carmelo Palma, "Proportional representation, a good idea that risks remaining a mirage", Public Policy , 6 May 2022).

The history of the Second Republic was, under many points of view, the history of a generous illusion, i.e. of the hope – which turned out to be vain – that with institutional engineering operations it would be possible to cure endemic ills of the political system. In the space of three decades, the country has thus been subjected to an unprecedented twist in the panorama of Western democracies: a series of electoral reforms, in two cases (Porcellum and Rosatellum) designed above all to cut the nails, respectively, of the centre-left and the Five stars; and, more generally, aimed at creating a two-party model from above, without however having the courage to impose it to the end, but by building a bizarre mechanism of pre-electoral coalitions. The result was "a limping hybrid, with ephemeral parties that merged and split every few months, forced alliances that vanished after each election, held together by the sole objective of preventing the victory of the adversary" (Francesco Cundari, "Fragile Constitution ”, Linkiesta Magazine , August 6, 2021).

In short, the transition that began with the referendum on the single preference (1991) never ended. The battle against the degeneration of parliamentarianism has taken on a palingenetic and even moral significance, by virtue of an analysis which attributed to proportionalism the responsibility of party politics, the source of all corruption, clientelism and backwardness, as well as of the unsustainable public debt. A justicialist opinion movement has thus established itself, which identified in the electoral referendums the decisive lever with which to pass from the "democracy of the parties" to the "decisive democracy", guaranteed precisely by the majority and by a bipolar coalition. A change equated to a constitutional change, not for nothing still told today, according to French usage, such as the transition from the First to the Second Republic. The result has been that every trivial government crisis has turned into a systemic crisis. This is why the political forces, when they weren't busy challenging each other on the electoral law, did so on the reform of the Constitution, where every attempt at broad understanding, from the "Bicamerale D'Alema" (1997) to the "Renzi referendum" (2016), it has aroused clamorous protests, with tones of civil war, which have always decreed its failure.

Of course, the crisis of mass parties and the decline of twentieth-century ideologies were underway well before the 1993 referendum, but the change in the electoral system has considerably accelerated both processes. With the result "that, when there was a government crisis and the letter of the Constitution and parliamentary practice were followed, building new majorities led by new prime ministers, the immediate reaction was triggered by vast sectors of public opinion who shouted coup and the betrayal of the popular mandate. They were wrong in point of law, but they grasped a real problem” (Cundari, ibidem).

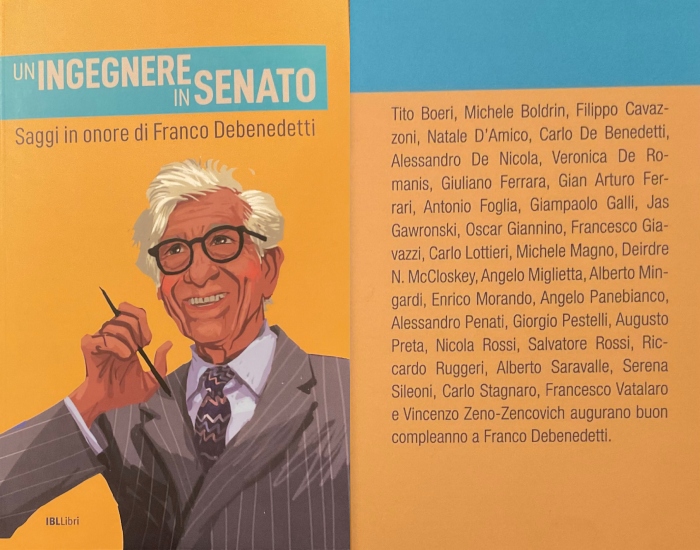

These critical notes are an auto de fe. Because the writer was in the past a partisan of the majority model. As, among others, Franco Debenedetti taught me, when the curtain fell on the "conventio ad excludendum", overwhelmed by the fall of the Berlin Wall, it seemed like a forced path. And yet, as Keynes (perhaps) said, “when the facts change, I change my opinion”. And the facts (I don't know if my friend Franco will agree) say that the season of the majority has been stingy with results not only in terms of means (governability), but also in terms of ends (structural reforms – as they were once called – economic, social and institutional). In fact, whatever the measure imagined to eradicate privileges and corporatisms, vehement opposition was triggered by the categories affected: monopolies, closed numbers, amnesties, insured careers, special indemnities, extensions and exemptions, ope legis, trade union guilds, professional orders and corporations of all kinds. They form a large and fierce army, and have often managed to get their way by inciting ruthless particularism and plundering public coffers.

It is against this wall that any reforming wind has broken. The anti-meritocratic and anti-competitive alignment has thus managed to neutralize the sphere of politics, imposing its impotence in exchange for its consent. We saw it in the last electoral campaign: amazing slogans, multiplication of loaves and fishes, protection of any positional income, lower taxes and more spending for everyone thanks to the magical budget deviation. On the other hand, we have witnessed the painful narrative of a country on the verge of poverty. A country that even in 2020 was in first place in Europe for the possession of homes, cars, mobile phones. On the second for pets. A country where the turnover linked to gambling – legal and illegal – was close to the amount collected from income tax. A country that, in order to know the future as wizards and witches, spent more than what is set aside annually for pension funds. A country in which there were more than eight million pensioners wholly or partially assisted by general taxation, three million people enjoyed basic income and another three million benefited from social shock absorbers: multiplied by the average number of dependents, there were about twenty million citizens who, in one way or another, were assisted by the state.

It is not enough. More than half of taxpayers in 2020 paid an income tax of fifteen billion euros. But the cost of ensuring the right to health, education and assistance for this half was twelve times higher. Difference filled by taxpayers with incomes exceeding thirty-five thousand euros, and who, alone, pay almost sixty percent of the Irpef. Finally, it is true that the number of people in absolute poverty has doubled in the last three decades. Without however forgetting that a large part of economic poverty derives from educational and social poverty from which almost ten million Italians suffer, many of whom are addicted to alcohol, drugs, gambling or other food problems such as anorexia and bulimia. A harsh reality which should also include those who find themselves in situations of sudden difficulty following early separations or divorces. Although, therefore, the number of poor people is rising, we are not a poor country. However, we are a country that has stratospheric tax evasion and an underground economy, and which among those in the OECD area boasts the sad record (after Turkey) of the highest index of functional illiteracy, while it is at the bottom of the ranking for dynamics of productivity and for investments in research ( Social Security Itineraries , Report 2021).

In the mid-seventies of the last century, the question of the middle class became central to the public debate after the publication of the famous Essay on social classes by Paolo Sylos Labini (1974). The pupil of Joseph Schumpeter, questioning a mantra of the Marxist vulgate, showed the growing weight of the middle classes (in the plural), above all the petty bourgeoisie of the agricultural, handicraft and commercial sectors (the infamous "mice in the cheese" ). And, while recognizing its importance, he attributed it above all to the patronage policies implemented by the DC. Today the question arises in different terms. Because the presumed decline of the middle class – of its status as well as its income levels – does not lend itself to easy journalistic simplifications. In fact, attention should be paid more to the widening of the gap between its upper and lower layers, or rather to the inequalities created by this gap. Trend first analyzed by Charles Wright Mills in his monumental research on "white collars" of 1951. In truth, a middle class never existed. Indeed, the middle class is a mixed salad of occupations, a nebula that includes self-employed workers (such as artisans, small and medium-sized entrepreneurs) and employees (such as public and private employees). When we want to refer to a whole that overcomes and includes these diversities, then the term class comes into play, which indicates a proximity of cultural traits, lifestyles, consumption models, also the effect of political choices.

The notorious social issue, therefore, does not only concern the rate of inequality, those who have low wages, a precarious job and are excluded or stationed on the margins of the "city of work". It calls into question the overall structure of our welfare. In the early 1950s, Thomas Marshall could argue that a drive towards equality was implicit in the welfare state under construction. When tested, this prediction turned out to be a mistake. Just think of the inability, even in the most interventionist versions of the welfare state, to eradicate the harshest and most mortifying forms of poverty as the very macho roots of the apparatus of citizenship rights. In other words, the historical experience of welfare leads to the affirmation of a thesis exactly opposite to that of the English sociologist, which only academic left-wing moralists can ignore, namely that freedom and equality can enter into conflict with each other. Also because social protections depend, to an extent that has no comparison with civil and political rights, on the resources created by the market. Challenged by demographic, family and work changes, welfare systems have been on the grill of governments since it was no longer possible to pay them by raising taxes. They were financed by borrowing. And the debt, sooner or later, must be repaid.

Unfortunately, the domestic political class has appeared insensitive to this warning. “All the defects and perhaps all the virtues of the Italian custom can be summed up in the institution of postponement: rethinking it, not compromising oneself, postponing the choice; keeping your feet in two stirrups, the double game, time makes up for everything, tries to live”, reads an aphorism by Piero Calamandrei. “It's better to live than to kick the bucket”, the totus politicus Giulio Andreotti ideally replied to the distinguished jurist. Both, albeit with opposite intentions, had acutely grasped one of the distinctive features of our national character. On the other hand, it was a disenchanted conservative like Giuseppe Prezzolini, founder of the Congregation of Apoti (that is, of "those who don't drink them"), who argued that among us there are neither ancestors nor posterity: there are only contemporaries. A self-absolute "contemporaneism", a sort of liberation of the responsibilities held towards past generations and the responsibilities one should have towards future generations.

Our most prestigious and authoritative personality, Mario Draghi , experienced it on his own skin. "Great is the confusion under heaven, therefore the situation is excellent": when he pronounced his famous maxim, Mao Zedong was referring to the chaos of Chinese society in the early 1960s, which according to the "great helmsman" would have favored the movement revolutionary. Here, on the other hand, more prosaically, it has awakened the "animal spirits" (electoral aliases) of those political leaders who were just waiting for a pretext to break the national unity pact.

[…]

*First part of the essay published in the volume “An engineer in the Senate. Essays in honor of Franco Debenedetti”, IBL, January 2022.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/la-stagione-del-maggioritario-una-generosa-illusione/ on Sat, 11 Feb 2023 06:04:42 +0000.