These are days in which the “assassins of memory” are back on the field

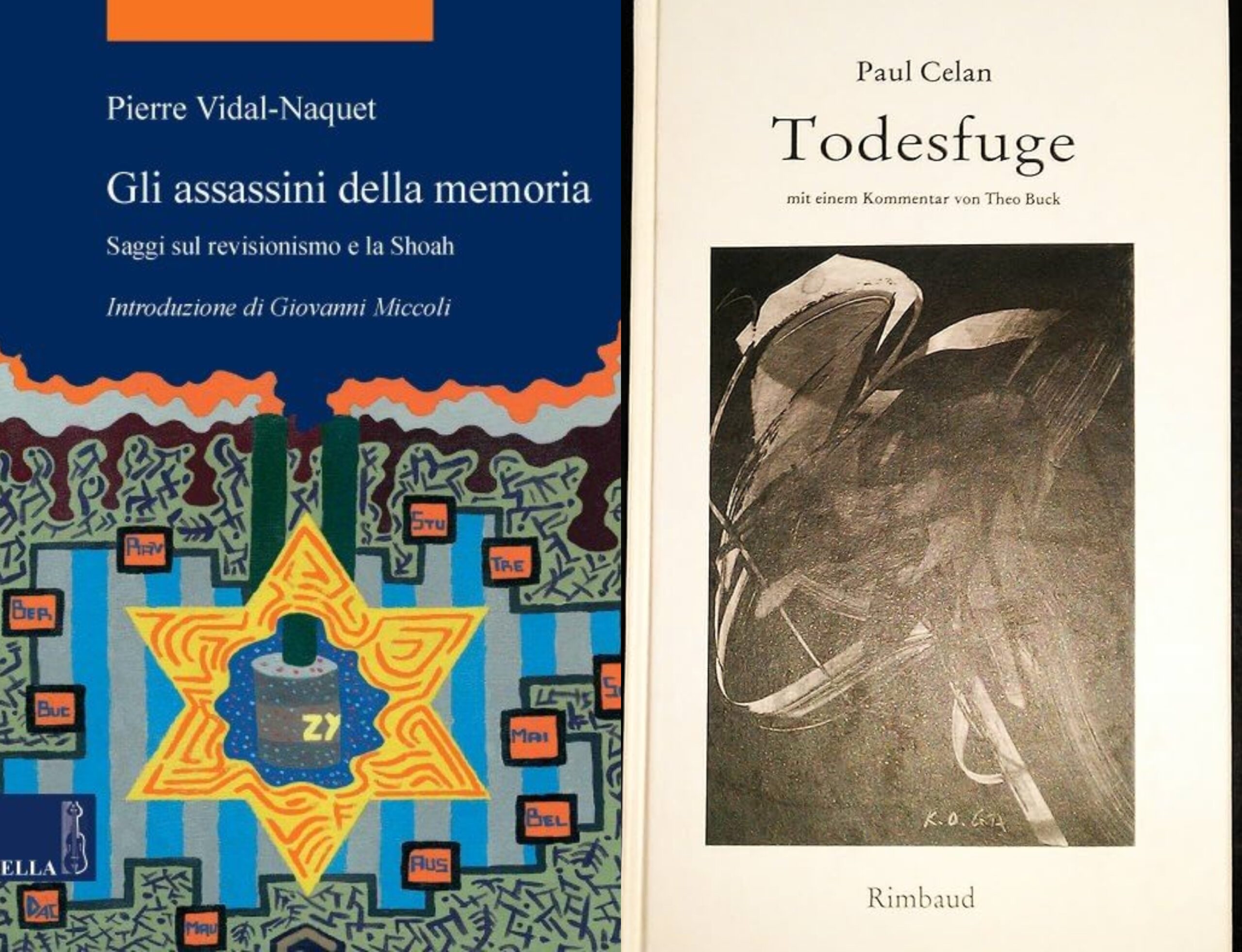

Michael the Great's Notepad

I apologize to the reader if I repeat a Notebook published in these columns on 20 November 2019 . However, these are days in which no longer creeping anti-Semitism, but open anti-Semitism is poisoning the public discourse on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In rare cases it is racial anti-Semitism (now cultivated only by esoteric sects). In others of social anti-Semitism, heir to the ancient hostility towards "usurers", the insult with which Jewish financiers were branded. But, in the opinion of the writer, it is above all a political anti-Semitism disguised as anti-Zionism, which denies Israel the right to exist and considers its state a military outpost of American imperialism. These are very difficult days, therefore. Days in which the "assassins of memory" ( Pierre Vidal-Naque t) returned to the field in numerous Western squares where "the sleep of reason generates monsters", as the title of the famous engraving by Francisco Goya states.

****

Born in Czernowitz in 1920, in Bukovina annexed to Romania after the end of the Great War, educated in Yiddish and German, the Jew Paul Celan – an anagram of Ancel (pronounced Zélan) – chose to deal with Auschwitz by composing verses about Holocaust in your native language. “Todesfuge” (“Death Escape”) is his most famous lyric. Begun in 1945, in his hometown, it was finished in Bucharest in the period between the deportation and murder of his parents in the Mikhaylovka camp, in Ukraine, and the extermination of the Jews of Bukovina.

Against Celan, Theodor W. Adorno argued that it was impossible to write poetry after Auschwitz. It was a paradox, used to mean that any attempt to describe the horror of the death camps through art was doomed to failure; and that, indeed, the very use of art represented almost an offense to the memory of the victims of the "Final Solution". Celan opposed the ban and created that lyric of lament in the infinite silence that is "Todesfuge", and refusing for years to meet Adorno (see Enzo Traverso, "Auschwitz and the intellectuals. The Shoah in post-war culture", il Mulino, 2004). Adorno later recognized the wishful thinking of his prescription. Primo Levi, in turn, accused him of having contradicted himself for having issued a sentence of condemnation while still using the written word, and replied that the only possible poem about Auschwitz was precisely Celan's poetry.

“Todesfuge” is, we can say, the poem about the extermination camps, even if they are never mentioned. There is talk of a Margarete with “golden hair”; there is talk of a Sulamith with "ashen hair"; and we talk above all about a mysterious "black milk" that "we" drink. It is not immediately clear who these two women are, why the milk is black, and who these “us” are; but, as we continue reading, we understand that all these images, these presences, allude to the extermination camps.

The translation of “Todesfuge” that I propose to the reader is by Giuseppe Bevilacqua, who was responsible for the care of the Meridiano Mondadori dedicated to Celan. Following is the comment by an essayist and historian of Italian literature, Claudio Giunta, which seems particularly insightful and apt to me.

Todesfuge

Negro milk of dawn we drink it in the evening

we drink it at noon as we drink it in the morning at night

we drink and drink

we dig a grave in the air whoever lies there is not cramped

In the house lives a man who plays with the snakes he writes

who writes in Germany when it darkens your golden hair Margarete

he writes he stands at the door and the stars flash

he gathers the mastiffs with a whistle

with a whistle he brings out his Jews and digs a grave in the earth

he commands us and now play because we have to dance

Negro milk of dawn we drink you at night

we drink you at noon as in the morning we drink you in the evening

we drink and drink

In the house lives a man who plays with the snakes he writes

who writes in Germany when it darkens your golden hair Margarete

your ash hair Sulamith we dig a grave in the air who lies there is not tight

He shouts, go deeper into the heart of the earth and you guys sing and play

he takes the iron from his belt and brandishes it, his eyes are blue

you aim your hoes deeper and you still play because you have to dance

Negro milk of dawn we drink you at night

we drink you at noon as in the morning we drink you in the evening

we drink and drink

in the house lives a man your golden hair Margarete

your ash hair Sulamith he plays with snakes

He shouts play sweeter death death is a Master of Germany

shouts hollow out the violins darker sound so you will go like smoke in the air

so you will have a tomb in the clouds whoever lies there is not cramped

Negro milk of dawn we drink you at night

we drink you at noon, death is a Master of Germany

we drink you in the evening as in the morning we drink and drink

death is a Master of Germany his eye is blue

he catches you with lead, he catches you with precise aim

in the house lives a man your golden hair Margarete

he turns the hounds on us and gives us a tomb in the air

he plays with snakes and dreams of death, he is a Master of Germany

your golden hair Margarete

your hair of ash Sulamith

Who speaks in this poem? Who are the "we" that appear already in the first verse? We don't understand it immediately, because the image that opens the text is enigmatic: in fact it speaks of a "black milk" that "we drink" at every hour of the day and night. The fourth verse answers our question: it is about prisoners "digging" a grave; and the following verses leave no doubt that we are in Germany, in a concentration camp, and that those prisoners are forced by one of the camp leaders to dig graves (which presumably are intended for them, or their companions ) both to play and dance.

The man who gives these atrocious orders is not a savage, he is a person who writes, reads, knows Goethe (Margarete is a character from Faust). But this very detail, evoked by the phrase "your blonde hair Margarete", makes the scene even more macabre and heartbreaking; it is as if Celan noted that one of the most refined cultures in the world – the German one – produced one of the most atrocious abominations in human history: Nazism, the planned extermination of the Jews. In the following stanzas the leitmotif of "black milk" returns, and the characters introduced in the first verse return, but the action continues: the camp guard doesn't just give orders, he becomes threatening, shows his gun, sets off his dogs, shoots, kills. Furthermore, Celan introduces, or rather evokes, a new character, a new name, Sulamith, the Jewish girl sung in the Song of Songs, who – with her ash, black and burnt hair from the crematorium – becomes the symbol of all Jews killed in the fields. And in the final two verses the two girls find themselves side by side: «your golden hair Margarete / your ash hair Sulamith» – simply, without comment, because the reader is now ready to understand the symbolic significance of these names, the their being images, respectively, of the German people and the Jewish people: the executioners and the victims.

The structure of the poem deserves careful consideration, because the title "Todesfuge" alludes to the articulation of the musical fugue, that is, that composition (the most famous are the fugues of the great eighteenth-century musician Johann Sebastian Bach) which develops starting from a theme main (subject) and some secondary themes (contrassubjects) which are then repeated several times (usually four) with slight tonal variations. In fact, this poem is also organized – just like a musical fugue – in four sequences of variable length which propose and rework the main motif of black milk, and a series of secondary motifs: the man in his house, Margarete with the blond hair , Ash-haired Shulamith, the music played by the prisoners. These motifs, however, are not developed in such a way as to communicate a meaningful message: they are instead evoked in the form of fragments that do not seem to have a precise relationship with those that precede and follow them, as if the poet (and his characters) is unable to understand the reality he is trying to describe, and sees everything as if through a fog, or in a dream.

In fact, the structure of the fugue gives the text a sing-song tone, almost like a nursery rhyme, and many of its details give us the impression of being inside a haunted world: the mysterious "black milk", the man with the snakes, the music that accompanies the dance, music that is 'directed' by a "German master" who identifies with death – it does not only seem like a 'death escape' but also one of those macabre dances that were painted on the walls of late medieval churches to remind the faithful that one must die (“memento mori”: “remember that you must die”, is the Latin phrase that accompanied these images).

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/sono-giorni-in-cui-gli-assassini-della-memoria-sono-tornati-in-campo/ on Sat, 18 Nov 2023 06:30:14 +0000.