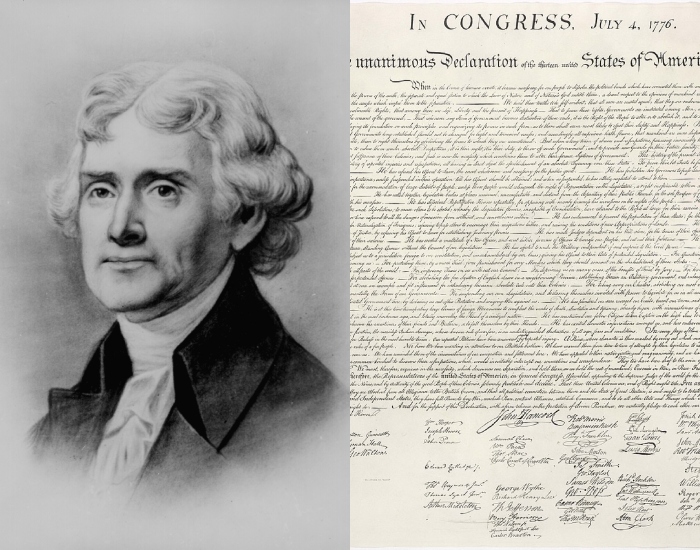

Thomas Jefferson and the origins of American democracy

Michael the Great's Notepad

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) is still today a point of reference for American libertarians, by virtue of his democratic-populist ideology still deeply rooted in the USA (see Paolo Zanotto, "The American libertarian movement from the 1960s to today", pdf ). Jefferson, first representative in the Virginia assembly and then elected to Congress in 1775, assumed the honors of "founding father of the country", for having distinguished himself among the leaders of the revolution thanks to his role in drafting the "Declaration of Independence ” of 1776. In 1779 he was elected governor of Virginia and from 1784 to 1789 he held the position of ambassador of the United States in France, a period during which he also made a trip to Piedmont and Liguria. Candidate in the presidential elections of 1796, he placed second behind his rival John Adams, of the "Federalist" faction, of which Jefferson became vice-president. Presenting himself again in the electoral consultations of 1800, he was tied for first with fellow republican Aaron Burr, so much so that it was necessary to resort – for the first time since the birth of the United States of America – to the vote of congressmen elected in the House of Representatives in a embarrassing run-off between the two. Jefferson won the day, thanks to the support given to him by the favorable vote of Alexander Hamilton's federalists, while Burr was appointed vice-president during his first term.

With the double mandate (1801-1809) of the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, a new phase in American history officially opened, marked by the so-called "epic of the frontier", which was characterized, in turn, by the "conquest of the West". If the federalist predecessors of Virginia, George Washington (1732-1799) and John Adams (1735-1826), during the first two successive presidencies from 1789 to 1801, had interpreted the Constitution in the sense of strengthening the central power held by the federal government, on the contrary the Jeffersonian republicans, or "democratic-republicans", fought in favor of a decentralization of political power, having at heart, rather, the rights of states and individual freedoms. From this contrast originated, in 1796, the first party system – which lasted until 1828 – in which Jefferson represented, in particular, the agrarian interests of the South. During the period of his two presidential terms, on the other hand, the society and the economy went through a particularly luxuriant period: the cities grew and beautified, in the New England region the textile industries consolidated, and in the South the cultivation of tobacco was partly replaced by that of cotton, which needed many black slaves. In this regard, shortly before definitively leaving the presidency, Jefferson passed a law in 1808 which prohibited the trade – but, mind you, only the trade – of slaves. Nonetheless, it must be that for Jeffersus racism – which he accepted by mistaking it for science – was an indispensable mechanism for making the plantation economy work".

As Malcom Sylvers wrote, “It was necessary to be able to brand, identify, separate and make the slaves despised by all to prevent their escape and to ensure the hegemony of the large planters over the other whites; the best kind of slave was therefore the black slave. Having wrested the land from the Indians and decided to exploit it in the South through extensive ownership, there was a risk of not being able to find the workforce. Forty years after Jefferson's death, Marx would tell, at the end of the first volume of Capital, of a capitalist who had brought workers and means of production to Australia; however, the plan did not work because once the first ones arrived – faced with the possibility of becoming independent farmers – they refused to carry out the task of employed workers" ("The political and social thought of Thomas Jefferson", Lacaita Editore, 1993).

Jefferson's presidency was marked by a strong pragmatism, which earned him the accusation of inconsistency by some critics and scholars. This independence from any ideological dogmatism has made it possible to describe the American intellectual and politician, from time to time, as a democrat or as his exact opposite. There are those who saw in him an anticipator of Roosevelt's New Deal, and those who, on the contrary, judged him a forerunner of his conservative opponents, those who considered him a kind of communist ante litteram and those who championed a fascist nationalism. In fact, the statesman who went down in history for stating that "the best government is the one that governs the least", is the same one who decided on a controversial expansion of the federal state with the purchase, in 1803, of the enormous territory of Louisiana from France of Napoleon, and with the push towards the progressive expansion towards the West of the country. Just as, despite being a convinced and strenuous pacifist, so much so that he reduced the army to a mere police force, he went as far as the coasts of Libya to bomb Tripoli in 1805, ushering in American military interventionism outside national borders.

Eight years of government not without contradictions, therefore, but in which the foundations of that democracy were laid which a few decades later Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) would analyze in his famous treatise, revealing its strengths and weaknesses , including the dangers of populism and Caesarism that are always lurking, above all when power "likes citizens to be happy, as long as they think only of being happy".

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/thomas-jefferson-e-le-origini-della-democrazia-americana/ on Sat, 15 Apr 2023 05:24:43 +0000.