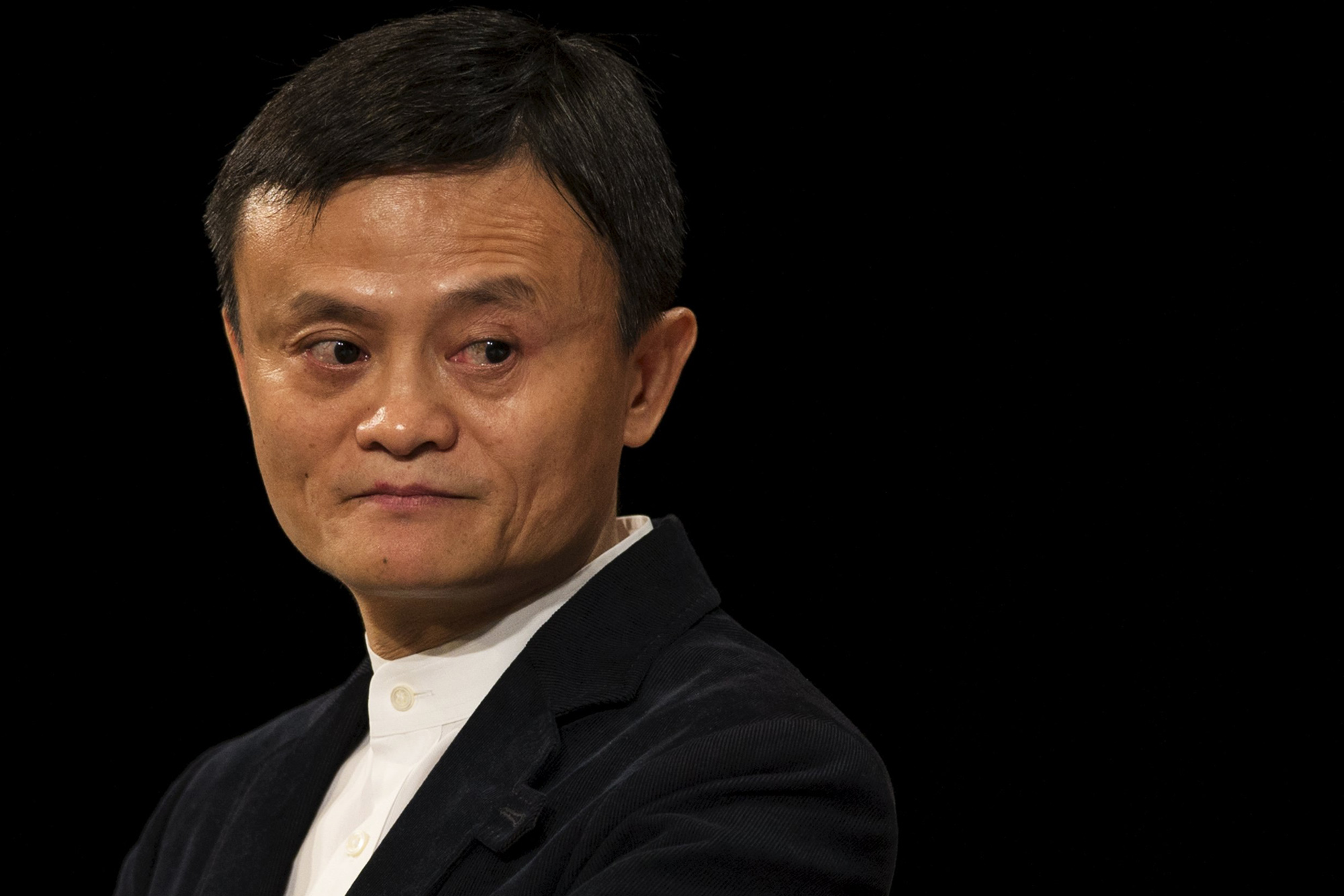

What the case of Alibaba’s Jack Ma hides

Mario Seminerio's comment, edited by Phastidio.net blog, on the Jack Ma case of Alibaba

Geopolitical and financial analysts from around the world have been wondering for many weeks on a question that apparently goes beyond the destiny of its protagonist: what happened to Jack Ma? What then would be the Chinese tycoon who created an online empire with Alibaba's e-commerce and physiologically extended it to financial intermediation and payment systems.

After his temper at the end of October against Chinese public banks, and after the Chinese regulator blocked the listing of Ant Group, a digital payments platform that serves over a billion users and 80 million merchants, what will happen? Between antitrust and data monopoly, let's try to understand.

The Chinese regulator, it is said at the direct impulse of Xi Jinping, blocked the listing of Ant Group, for which investment banks around the world were already looking forward to collecting fabulous commissions, on the grounds that the company would violate antitrust directives and prudential rules of financial intermediation. Since then, an "interlocution" has begun, or rather a monologue, in which the state speaks and Ma and her listen, disappearing from public radar.

Ant's app is a real drain of personal data: debtors and customers, consumption habits, travel, utility payments and so on. The company also provides loans but does so as a broker, that is, by acquiring funds from "traditional" banks (over a hundred of those involved so far), so it has little or no credit risk on its own, another heavy importance of the regulator. Not satisfied with this comfortable positioning, in his famous late-October speech, Jack Ma accused the Chinese public commercial banks of having a "pawn shop" mentality.

THE MULTIFORM RATING OF STATE

Then there is the question of data, at various levels. Firstly, it should be known that the Chinese central bank in the past tried to create a sort of centralized rating agency, to which intermediaries would have to contribute with the customer data in their possession. But Ant refused to supply its own, fearing for its competitive position. It is difficult to keep the dynamics of private debt under control, without the cooperation of operators. This is therefore probably the other critical element for the regulator. Which, after having "normalized" Ant, seems to have finally come to create the credit scoring system .

The "Ant question" is not so much that of a brilliant tech entrepreneur harassed by a liberticidal government as that, very familiar even in the West, of digital platforms that hoard customer data and, with their size, risk hindering some forms of control by the policy maker, in the specific case both competition between merchants and control of credit aggregates. Issues that are now or should be widely known even in our democratic lands.

THE PAY BOOK OF PLATFORMS

In their hitherto irresistible rise, platforms coax power. More properly, they aim to put it on the payroll. This, for Jack Ma and his Over the Top, meant, for example, cooperating with the authorities by providing the tracking data of subjects "attentive" by the regime. From this cooperation, as well as from the sale of shares at a "subsidized" price to public bodies and senior party officials, a benevolent negligence by the regulator with respect to issues such as abuse of dominant position and financial risks derives or should result.

At least, this is what Jack Ma thought and thought or perhaps still think, the demiurges who manage the US platforms, after the ousting of Donald Trump from their social networks. A banishment that, let us remember, takes place in formal compliance with the terms of service and private contracts with users, but whose timely zeal could maliciously be placed in connection with the now unavoidable issue of editorial responsibility for content, the famous Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which OTTs see as the basis for their survival and prosperity over the years.

Returning to China and Ma, I believe it can be said that the story marks the intersection of two major plans: on the one hand, an apparently genuine antitrust orientation, to avoid that emerging and promising companies are suffocated by the incumbent, and an equally felt need for not to jeopardize national financial stability by allowing an e-commerce giant to take over the creditworthiness of the banking system.

On the other hand, and as a consequence of failure to control the gigantism of others, it seems quite clear that, from a financial catastrophe caused by an unscrupulous use of credit by an operator (without jeopardizing its own capital), the party has only to lose: eventually, their own political monopoly.

MONOPOLY IN THE “LEGITIMATE” USE OF DATA

With that cynicism that usually serves to read reality, we could say that data is like "legitimate" violence: a state must have a monopoly of use. The problem is that this need does not appear limited to the Chinese dictatorship but also to the rest of the free or presumed free world.

It starts from the understandable need to repress activities that are peacefully considered repugnant, such as sex trafficking through the Net, to the more general copyright infringement (all things already regulated by Section 230), and we arrive at "free speech", in meaning more and more widely understood, and to the delimitation of hate speech, which is nevertheless likely to be in the eyes and ears of those who read and listen, within certain limits.

We therefore have a tension towards a monopoly in the use of data intended as a strategic lever of social control, which fatally goes beyond the habits of consumption of goods and services. The point of clash between an economic elite who would like to "only" drive consumers but which inevitably ends up in "politics", that is, in the context of another and different elite, which beyond certain limits can no longer be satisfied with being bought by the first without putting his own survival at risk. It starts with personal loans, you get to the social rating for the evaluation of the "good citizen", remember?

This is why the story of Jack Ma is neither nor can it be different from those of Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, Sundar Pichai, Jeff Bezos and others.

Article published on phastidio.net

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/jack-ma-alibaba/ on Sun, 17 Jan 2021 06:10:34 +0000.