The seismic history of Ischia between reality and myth

Michael the Great's Notepad

The following text is an excerpt from an interesting essay by Giovanni Gugg, professor of urban anthropology at the Federico II University of Naples, published on August 21, 2018 on the collective blog "il lavoro cultura". It is entitled "The plots of Casamicciola". It is a story, between reality and myth, of some episodes of the seismic history of Ischia. Thinking of the controversies surrounding the tragedy that has hit the island in recent days, one comes to mind – very famous – which in the eighteenth century had Voltaire and Rousseau as protagonists.

“Lisbon is destroyed and people dance in Paris”: this is how Voltaire wrote immediately after the earthquake that on 1 November 1755 razed the capital of Portugal to the ground. As soon as he learns of it, the Enlightenment philosopher composes the "Poem on the Lisbon disaster", in which he rails against the religious optimism of Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz. In his "Theodicy", the German scientist and thinker had stated that humanity lives "in the best of all possible worlds". Voltaire rejects this assertion, and wonders how a world in which tragedies such as the one that had exterminated tens of thousands of innocent people can be defined in this way. A controversy to which Leibniz, who died in 1716, could not answer, but which opens an intellectual dispute destined to profoundly mark the very idea of modernity.

In addition to Leibniz, Voltaire targeted the English Catholic poet Alexander Pope, who in his "Essay on Man" (1730-1732) had argued that "one truth is clear: whatever exists, it is right". And it is precisely to the philosophers "eternal comforters of useless pains" that Voltaire addresses himself from the heartfelt and angry first lines of his "Poem": "Poor humans! Our poor land! Terrible accumulation of disasters! Eternal comforters of useless pain! Philosophers who dare to cry out: All is well, come and contemplate these horrendous ruins: broken walls, shredded flesh, ominous ashes. Women and infants piled one on top of the other under pieces of stones, scattered limbs, a hundred thousand wounded that the earth devours, tortured, bleeding but still throbbing, buried under their roofs, they lose their miserable lives without help, amid atrocious torments ”. Furthermore, he provocatively asks: “To the faint moans of dying voices, to the pitiful sight of smoking ashes, you will say: is this the effect of eternal laws which leave no choice to a free and good God? You will say, seeing these piles of victims: was this the price that God made to pay for their sins? What sins, what faults did these crushed and bleeding infants commit on their mother's womb?

The "Poem" had an enormous diffusion throughout Europe, with numerous printed editions. One of the first manuscript copies was sent by the author to Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The Genevan philosopher replied to him with a long letter (August 1756), in which he contested his radical pessimism and underlined the responsibility of men: "Remaining on the subject of the Lisbon disaster, you will agree that, for example, nature had by no means that place twenty thousand houses of six or seven floors, and that if the inhabitants of that great city had been distributed more evenly over the territory and housed in buildings of less impressiveness, the disaster would have been less violent, or perhaps it would not have occurred at all. Everyone would have fled at the first shock and would have found themselves the next day twenty leagues away, as happy as if nothing had happened.

A young Immanuel Kant also enters the discussion, distancing himself from strictly theological interpretations, clarifying that natural catastrophes must lead man not to consider himself the sole and exclusive end of the universe. Kant not only criticizes the fatalistic and superstitious approach to natural disasters, but publishes three essays on earthquakes (1756). His theory was based on the presumed presence in the subsoil of enormous caverns saturated with hot gases. Thesis soon superseded by subsequent discoveries, but which will remain the first attempt at a scientific explanation of the phenomenon . (Mi.Ma)

The plots of Casamicciola

In the popular literature of Ischia it is said that Tifeo resides under the island, a giant with a hundred heads who, to realize the ambitions of his mother Gaia, rebelled against Zeus, who, however, prevailed after a ferocious struggle and confined him underground of the island of Pithecusae, which thus began to erupt fire and to have hot waters, as well as to undergo shaking due to the restlessness of the monster. Although the myth of Typhon was born in Cilicia, his use as an allegorical figure of the unstable geomorphology of Ischia is due to the importance of the island in the classical age as a "crossroads of the ancient world" and he has adapted so well that there is a reflection also on the surface, through the popular and official toponymy that describes the places precisely in its function, such as for example the village of Panza, the fumaroles of La Bocca and other localities.

In the founding legend of Ischia, Typhon is a dragon who wants to take the place of Jupiter, but whom the father of the gods manages to stop by hurling the island at him, so as to crush him with Mount Epomeo. Trapped underground, however, the monster is not dead, so from time to time it wriggles and spits fire, which provides not only the subject of a popular narrative, but more profoundly a picture of meaning that, from generation to generation of Ischia , has made it possible on the one hand to underline one's local belonging and, on the other, to exorcise fears and to find accessible explanations for events considered exceptional.

Despite the last eruption dating back to 1302, Ischia, in fact, is one of the three active volcanoes in the province of Naples together with Campi Flegrei and Vesuvius. From a geological point of view, the duration of its cycles of alternation between quiescence and active phase is typically 10,000 years. This involves long phases of apparent absence of activity, sporadically interrupted by low-magnitude earthquakes located at a shallow depth in the north of the island and accompanied by widespread fumarolic and hydrothermal events. It should be noted that, as it is still active, the Ischia volcano is potentially capable of erupting in the future, with particularly worrying effects due to the intense urbanization that affected its territory during the twentieth century.

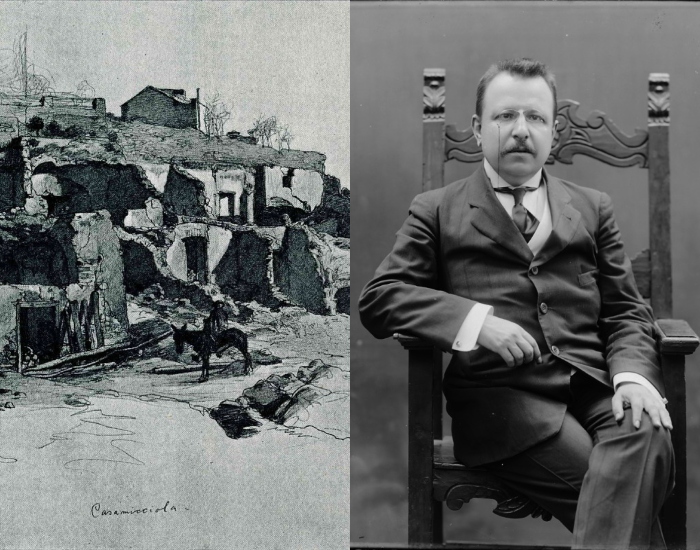

The seismic history of the island begins in 1228 and has the typical characteristics of seismicity in volcanic areas, ie earthquakes of low energy but of high intensity. Most of the seismic events recorded in the last eight centuries have as their epicenter the northern slope of Mount Epomeo, the one corresponding to the municipalities of Casamicciola Terme and Lacco Ameno. The nineteenth century was the century with the most earthquakes: in 1828 there were some victims and various material damages in Casamicciola, leaving their memory in the collective memory for several decades, at least until the catastrophic shock of 28 July 1883, which was preceded by strong telluric movements already in 1880 and 1881. The earthquake of 1883, the first in united Italy and the most intense ever recorded in Ischia, is also the most widely documented both in literature and in archival sources: it caused 2,333 deaths and destruction of the historical and environmental heritage of some areas of the island; the greatest damage occurred in Casamicciola and Lacco Ameno, where out of 1,061 houses surveyed only 19 remained standing (only one in Casamicciola).

At the time, Ischia was the destination of wealthy and international tourism, attracted by the presence of establishments for thermal treatments and by the salubrity of its sea, so the seismic disaster had a great reverberation in the national and foreign press and a considerable emotional impact, which gave birth to a saying, which soon spread throughout the country: "A Casamicciola happened", as an expression of ruin, disorder, confusion. The best known direct testimony of that catastrophe is from Benedetto Croce, seventeen years old at the time, the only survivor of his family after the collapse of their vacation home, who tells of that terrible experience in his "Contribution to the criticism of myself" (1918) and the "Memoirs of my life" (1966):

“I came to in the middle of the night and found myself buried up to my neck, and the stars glittered on my head […]. Towards morning (but later), I was pulled out, if I remember correctly, by two soldiers and stretched out on a stretcher in the open air. The stupefaction of the domestic misfortune that had struck me, the morbid state of my organism which did not suffer from any specific disease and seemed to suffer from all, the lack of clarity about myself and the way forward, the uncertain concepts about the ends and the meaning of living, and the other joint anxieties of youth, robbed me of all joy of hope and inclined me to consider myself withered before flowering, old before young”. The earthquake changed Croce's life both in his affections and in his thoughts: "Those years were my most painful and darkest: the only ones in which many times in the evening, resting my head on the pillow, I strongly yearned not to wake me in the morning, and I even have thoughts of suicide.”

The Casamicciola earthquake represents the first serious catastrophe that the national government had to deal with, which promulgated the first anti-seismic legislation in the post-unification period with a certain haste. The "Building Regulations for the Municipalities of the Island of Ischia damaged by the earthquake of 28 July 1883" entered into force on 15 September 1884 – with "indefinite validity" – and indicated the requirements for new buildings (it was recommended to use the "shanty" system), the definition and delimitation of "dangerous areas", the rules for damaged and unsafe buildings, the establishment of the Special Building Commission with the task of carrying out and having carried out the provisions contained in the Regulations.

Among the numerous political and scientific personalities who intervened on the scene of the disaster, significant work was undertaken, on the political level, by Francesco Genala, Minister of Public Works, and, on the cognitive level, by Giulio Grablovitz, founder and director of the Geodynamic Observatory of Casamicciola, who arrived in Ischia in 1884, where he would remain for the rest of his life. During the emergency and in the reconstruction planning phase, Minister Genala's choices were decisive: he stayed on the island for about a month, visited the most damaged places, followed the scientific debate which attributed the extent of the damage to the way of building and, as mentioned, favored the promulgation of the Building Regulations. The year after the earthquake, however, Grablovitz landed on the island, who studied the geological nature of the territory by developing one of the first monitoring systems for an active volcano and taking concrete steps to disseminate the results of his research to the population.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/mondo/la-storia-sismica-di-ischia-tra-realta-e-mito/ on Sat, 03 Dec 2022 06:31:57 +0000.