Will the ECB’s maxi purchases end in 2021?

What will happen in 2021 between central banks and fiscal policies? The analysis by Andrea Delitala, Head of Euro Multi Asset, and Marco Piersimoni, Senior Investment Manager of Pictet Asset Management

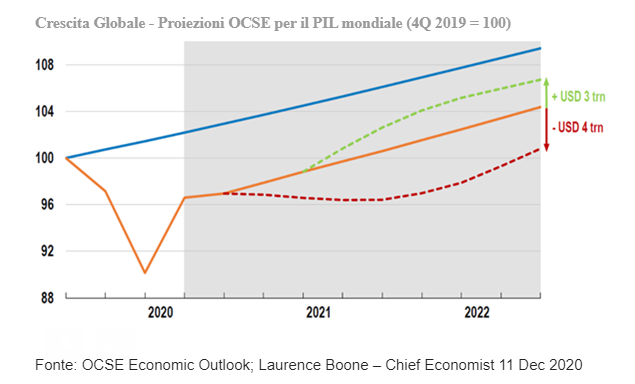

Judging by the financial markets, 2020 doesn't seem like such a bad year. Yet, while stock markets, driven by expansive monetary and fiscal maneuvers, venture to new highs (the S&P 500 broke the 3'700 point barrier), the world is still grappling with the second wave of the Covid pandemic- 19 , which brought the health, economic and social system of the entire planet to its knees. As the year draws to a close, the good news regarding the creation of effective coronavirus vaccines has stepped in to restore hope of a return to normalcy to citizens, businesses and governments around the world. From an economic point of view, this would mean a return of the global economy on a trend growth path, albeit at a lower level than the pre-pandemic one (in the base scenario developed by the OECD, so that global GDP returns to the end of 2019, it will be necessary to wait until the last quarter of 2021). But the uncertainty remains high and is reflected in the dispersion of forecasts: will the administration of the first doses of the vaccine be sufficient to avoid a third wave of infections? Will people actually be willing to take the vaccine? Will it be possible to reach the threshold of immunized subjects necessary to obtain herd immunity? These are some of the questions to which it is currently difficult to find a definite answer and which make the exercise of making economic forecasts for 2021 particularly complicated (the gap between the best and worst case scenario of the OECD is $ 7,000 billion, around 8% of world GDP of nearly $ 88,000 billion at the end of 2019).

The state of extreme uncertainty is not the only legacy of this 2020 under the banner of the pandemic. Like a devastating earthquake, the coronavirus has produced profound economic and social fractures. If, in fact, on a global level, the growth differential between emerging countries, with Asia and China in the lead, and developed countries, among which Europe has lagged behind most of all, has widened, in the same way it is inequality between social classes has increased, with data showing that the most affected by the wave of unemployment caused by Covid are the lower income classes. A problem particularly felt in Anglo-Saxon countries and especially in the United States, where there are no social safety nets such as layoffs (not surprisingly, during the peak of the crisis this year, the Trump administration was forced to make substantial direct transfers to citizens ). The repercussions could be deeper and more lasting than expected, as even among children, those from the lowest-income quartile were able to use online education to a much lesser extent than their peers in wealthier families. The imbalance is so great that even Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has felt the need to name him multiple times over the past few months.

As a positive effect of the coronavirus, awareness of the urgent need to act to protect the environment has spread even more this year than in the past: the decline in CO2 emissions recorded in 2020 has shown that it is still possible to have an impact beneficial. In this case, the issue is particularly hot in Europe. The Old Continent has always been at the forefront of environmental policies, setting first the goal of net zero emissions by 2050, and has recently revised the intermediate objectives for 2030, making them even more stringent: now we are aiming for a reduction emissions by at least 55% compared to the 1990 base level (previously, the target for 2030 was a 40% cut).

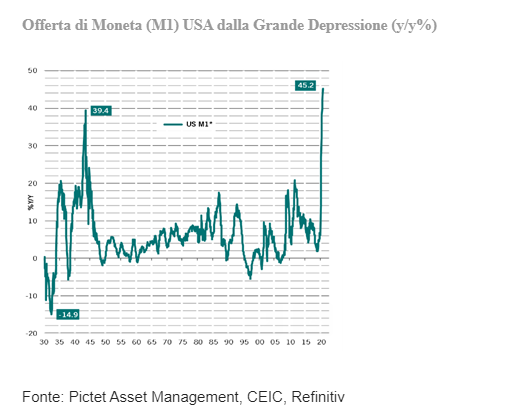

After more than a decade dominated by central bank intervention (from the great financial crisis onwards), 2020 will probably also be remembered for the passing of the baton from monetary to fiscal policy. The first, in fact, now seems to have little room for maneuver left, after having injected a record amount of liquidity into the economic system this year in an attempt (so far successful) to guarantee its financial stability.

This does not mean that the support will fail, on the contrary the financial conditions will remain supportive for a long time (it is difficult to imagine rate hikes, especially the real ones, before a few years from now), but the intervention of fiscal policy is now required. . And to heal the scars left by the pandemic, fiscal measures will be needed that go beyond the pure economic situation, no longer simply anti-cyclical, but of a structural nature.

On the basis of what has been said so far, in Anglo-Saxon countries the action of governments will be aimed above all at reducing economic and social inequality, while in the European Union the green rule seems to finally lead to overcoming ideological divisions within the region and to sharing common budgetary policies, sometimes also with redistributive purposes. In this context, Italy certainly finds itself enjoying particularly favorable financial conditions due to two concomitant factors: 1) compression of risk premiums well below the norm (the fair value of the credit risk component would be around 180bps) and 2) thanks to the Next Generation Eu, Italy becomes a net borrower of loans (and transfers) in the EMU context. This virtuous circle brings the cost of the new debt close to 0 with savings in interest expenses (today around 3.5% of GDP) which, as long as the average rates at issue remain at such low levels, are gradually transmitted to the large stock of debt (158% of GDP). To ensure that the market remains lenient towards the BTP even in the moment (still distant, not before 2022) in which the support of the ECB will cease, Italy must necessarily take advantage of the current opportunity to make reforms and present itself between a few years with a newfound competitiveness. And who knows that the world to come will not be better in the end.

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/economia/nel-2021-finiranno-i-maxi-acquisti-della-bce/ on Fri, 01 Jan 2021 07:24:52 +0000.